Mozart after Mozart

Editorial Lessons in the Process of Publishing J. N. Hummel’s Arrangements of Mozart’s Piano Concertos

Table of contents

DOI: 10.32063/0202

Leonardo Miucci

Fortepianist and musicologist Leonardo Miucci is currently developing a PhD research project about Beethoven’s piano sonatas (with patronage of Beethoven-Haus Bonn) and releasing the critical editions of Hummel arrangements of piano concertos (HH Editions) and their recording on original instruments (Dynamic). Since 2010 he has been a researcher for the Bern Hochschule der Künste.

by Leonardo Miucci

Music + Practice, Volume 2

Scientific

Mozart piano concertos: scary skeletons or sacred scores?1)I am indebted to Bianca Maria Antolini, Thomas Gartmann, Anselm Gerhard, Christina Kobb and Giorgio Sanguinetti for various suggestions in the preparation of this article. Thanks also to Rachel Deloughry for her assistance with the English editing of earlier drafts.

Even today, performing Mozart piano concertos still poses various problems involving numerous fields of knowledge; from mastery of style and improvisation to the critical and philological awareness of its historical background. Unfortunately, both performers and publishers seem to be reticent and still deep-seated on the 20th century values: the former – with the exception of a few personalities mainly researching and performing on historical instruments – limit themselves to reproducing on stage what they see in modern scores (providing them with a historically incorrect sacredness), while the latter are content with the achievements accomplished by the Urtext editions, whose sterile results, in several cases, should be taken over by a new approach.2)On this topic, see: Christopher Hogwood, ‘Urtext, que me veux-tu?’ in Early Music, 41/1 (2013), pp. 123-27. In fact, the editorial practices of the Urtexts, along with the often exaggerated Werktreue of modern performers may represent the least beneficial approach to this much-loved repertoire; The Literary Gazette in 1825 referred to solo parts in Mozart’s piano concertos as ‘barren and deficient… mere skeletons’.3)The Literary Gazette, Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences, & c., London, vol. 437 (June 4th 1825), p. 364. For the full quote, see the text preceding footnote 19 below. (No wonder that performers and publishers alike have been scared, when instead of notes, they found skeletons in the scores!)

A source hitherto unacknowledged when considering Mozart piano concertos, is Hummel’s piano quartet arrangements of seven of these. For the first time, these transcriptions are now being made available in a modern edition as a part of a research project developed at the Hochschule der Künste, Bern, having as topic the keyboard improvisation practice in early 19th century Vienna.4)This seven-concerto collection, released by the British publisher Edition HH (http://www.editionhh.co.uk/) is edited with the valuable collaboration of Costantino Mastroprimiano and with the precious support of the Research Department of the Hochschule der Künste of Bern (http://www.hkb-interpretation.ch). The first issue, KV 466, was released in June 2013 while the second one, KV 456, in February 2014 and KV 503, in September 2015. This collection is only one of the outputs of a research project called ‘Beethovens «Fantasie» – Between composition and music theory, improvisation and performance practice of piano players around 1800’. This research project led to the international Symposium «Improvisieren – Interpretieren», which took place in Bern HKB in October 2013 and whose papers will be soon published by Argus.(http://www.hkb.bfh.ch/en/research/forschungsschwerpunkte/fspinterpretation/veranstaltungen/improvisieren/) In the process of this work, an apparently underestimated but extremely determining fact emerged as the main philological and performing obstacle: W. A. Mozart, with the exception of certainly six concertos (KV 413-415, 451, 453, 595),5)Indeed, KV 413-415 were sold in manuscript copies. They were published by Artaria in Wien in 1785 and Mozart, famously, had written to his father (28 December 1782) that ‘Die Concerten sind eben das Mittelding zwischen zu schwer, und zu leicht – sind sehr Brilliant – angenehm in die Ohren – Natürlich, ohne in das leere zu fallen – hie und da – können auch Kenner allein Satisfaction erhalten – doch so – daβ die nichtkenner damit zufrieden seyn müssen, ohne zu wissen warum‘. did not take part in any publishing process which handed down to our generations the text as we know it. The majority of this repertoire had been realised posthumously, initiated by the interest (and economical needs) of his widow Constanze and of the publisher André, (followed by Artaria and Breitkopf & Härtel).6)For example, André released in 1792, as first editions, the concertos KV 271, 449 and 456. The only sources available to the publishers, therefore, were the manuscripts used by the composer during his performances. This circumstance produced consequently an editio princeps which is largely deficient in several respects: besides the lack of articulation and interpretative marks, this tradition is inadequate even regarding the completeness and unambiguity of the piano part. In fact, owing to his usual rush in preparing the scores, Mozart would often enter the stage with nothing but a sketch of the piano part, which he – being the soloist – would complete during the performance. In other words: these manuscripts were not intended for any other keyboard player than himself. This performance habit is confirmed by several historical reports; in 1798, for instance, Friedrich Rochlitz, in his Anekdoten aus Mozarts Leben, states that Mozart, when had to perform his piano concertos, was bringing with him only the complete orchestral parts, while he was used to play from a piano text which included just a figured bass line, and only the main themes, in some sort of sketchy notation, which the composer completed on stage, thanks to his performing skills and memory.7)See Friedrich Rochlitz, ‘Anekdoten aus Mozarts Leben’, in Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, 1 (1798), p. 113. Furthermore, this circumstance passed on specimens of Cadenzas and Eingänge whose recipients and style are, at least, still sources of debate.8)The reader is referred to the extensive literature on the subject: Eva and Paul Badura-Skoda, Mozart- Interpretation, (Wien: Edward Wancura Verlag, 1957); Frederick Neumann, Ornamentation and Improvisation in Mozart (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986); Robert D. Levin, ‘Instrumental Ornamentation, Improvisation and Cadenzas’, in Performance Practice, Music after 1600, ed. by H. Mayer Brown and S. Sadie (New York: Norton, 1990) pp. 267–91; Philip Whitmore, Unpremeditated Art: The Cadenza in the Classical Keyboard Concerto (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991); Christoph Wolff, ‘Cadenzas and Styles of Improvisation in Mozart’s Piano Concertos’ in Perspectives on Mozart Performance, ed. by L. Todd (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991) pp. 228-38; Robert D. Levin, ‘Improvised Embellishments in Mozart’s Keyboard Music’ in Early Music 20 (1992), pp. 221–34; David Grayson, ‘Whose Authenticity? Ornaments by Hummel and Cramer for Mozart’s Piano Concertos’ in Mozart’s Piano Concertos: Text, Context, Interpretation, ed. by N. Zaslaw (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996) pp. 373–91; Leonardo Miucci, ‘I Concerti per fortepiano di Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: le trascrizioni di Johann Nepomuk Hummel’ in Rivista Italiana di Musicologia, 43/45 (2008), pp. 81–128. In regard to this last consideration and to the Rochlitz report, see, for instance, what Mozart writes to his father, responding to his sister’s request (as she was preparing a performance of the KV 451 concerto):

… Nannerl is quite right in saying that there is something missing in the solo passage in C in the Andante of the concerto in D. I shall send it to my sister as soon as possible together with the cadenza.9)Letter of 9 June 1784, see: NMA, V/15/5, p. 208

And on another request by Nannerl, this time in regard of an Eingang for the finale of the concerto KV 271, Mozart commented: ‘I always play that which comes first to my mind’!,10)(‚wenn ich dieses Concert spielle, so mache ich allzeit was mir einfällt‘), in Mozart Briefe und Aufzeichnungen, 243, 22 January 1783. – which forces us to realize that the ‘Urtext’ so eagerly searched for may indeed have intentional gaps.

As such, the modern publication of the Hummel arrangements represents a turning point: rather than providing the researcher and performer with definitive answers, the edition searches to encourage a wider process of consideration, which it is hoped will contribute to a more genuine approach to this literature.

The improvising soloist

‘I always play that which comes first to mind’: the practice of the improvising soloist

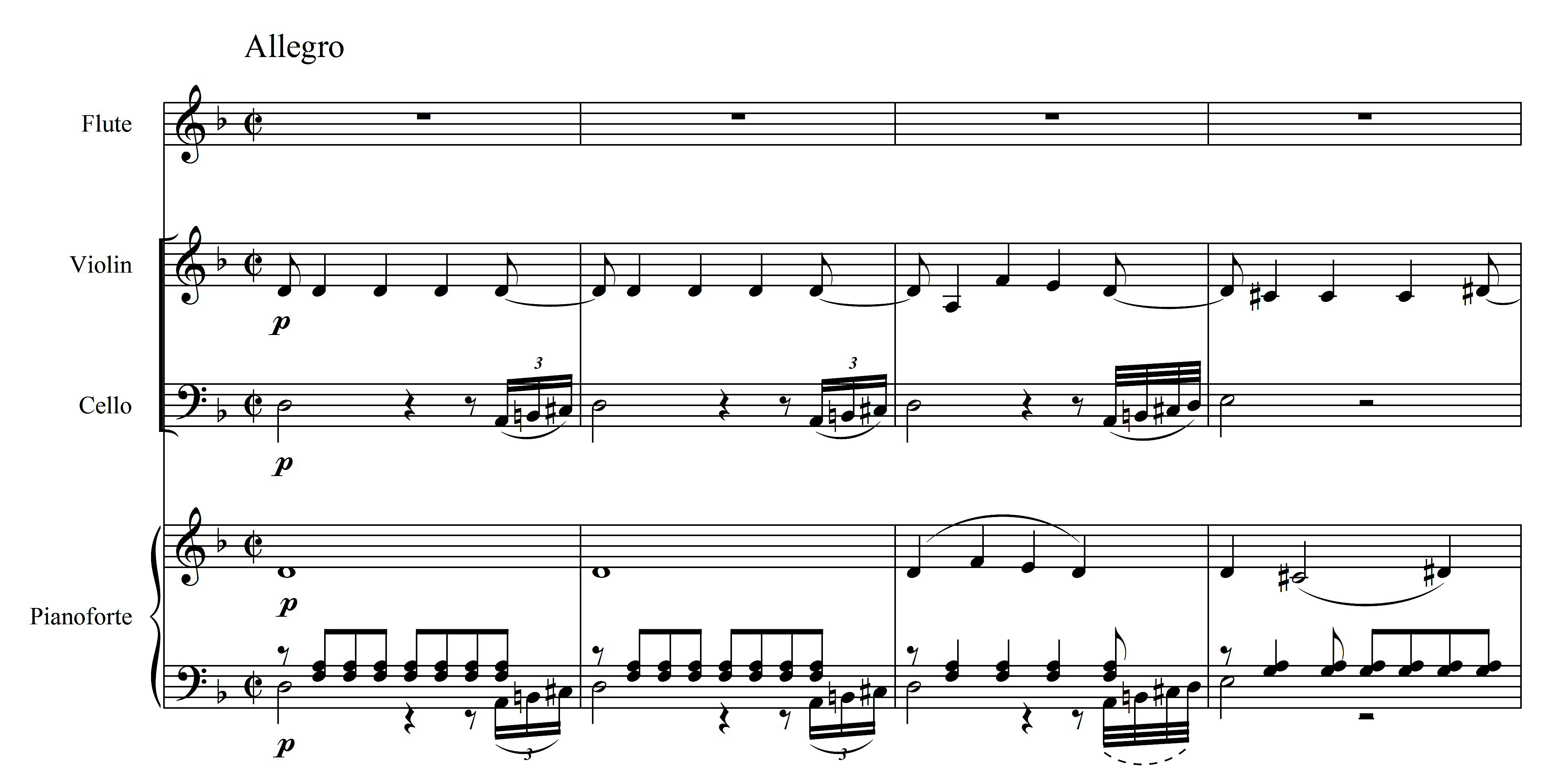

Fully in line with performance directions expressed in numerous other sources of the 18th and early 19th centuries, Hummel proposes that the soloist adds to the part supplied by the composer. As this practice is especially pertinent to slow movements, a fragment of the Romance from the D minor concerto, KV 466, is a relevant example (Figure 1).

At first, such embellishments might seem exaggerated, certainly contributing more to the quantity than the quality aspect of the work. But, a comparison with coeval sources may explain the historical coherency of this practice: a similar approach, indeed, is suggested by several treatises (among them the one of Türk ),11)See: Daniel Gottlob Türk, Clavierschule, oder Anweisung zum Clavierspielen (Leipzig and Halle: Schwickert, 1789). Such a performance practice, indeed, is traceable as well in several other treatises conceived for different instruments than keyboard; see, for instance, Quantz’s and Tartini‘s examples: Johann Joachim Quantz, Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversière zu spielen, (Berlin: Voβ, 1752); with regard to Tartini, a new critical edition of the complete theoretical and didactic works is about to be released, published by SEdM (www.sedm.it) and edited by M. Canale. or even by several piano works conceived by Mozart with publishing aims (as the Piano Sonatas KV 332 and 457 or the Rondò KV 511). What may be seen as a final proof of the possibilities and models to complete such a sketchy text, comes from a very important (and still underestimated) document, whose handwriting had been attributed by Wolfgang Plath to Barbara Ployer, one of Mozart’s most talented students.12)See: NMA edition of KV 488 (V/15/7), KB pp. g/10-4 and g106-09. This manuscript, held in the Staatsbibliotheck of Berlin,13)Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Mus. Ms. 15,486/5. reproduces the piano solo part of the F sharp minor Adagio (KV 488), to which is added a third staff containing the right hand embellishments (Figure 2).

Figure 2 B. Ployer, embellished version of Mozart Piano concerto in A major, KV 488, ‘Adagio’, bars 22-28.

This document has received little consideration due to the impossibility, at the present state of sources, to link it directly to Mozart’s authorship.14)See, for example: Neumann, Ornamentation and improvisation, pp. 247, 251-53. Nevertheless, Barbara Ployer probably prepared a performance of this concerto and therefore wrote down the embellished version of what she was supposed to play in the slow movement, as she was not a master (and therefore not capable of the extent of improvising required from relying on the original sketchy text).15)See: Robert D. Levin, ‘K. 488: Mozart’s Third Concerto for Barbara Ployer?’, in Mozartiana. The Festschrift for the Seventieth Birthday of Professor Ebisawa Bin, (2001), pp. 555-70. It is hard to believe she accomplished this task without any supervision and/or suggestion by Mozart: sources have proved the extent to which the composer meticulously provided the completed version of the piano texture of his concertos, when anyone other than himself was about to perform them.16)In this respect, Mozart did not even trust his sister, who was supposed to deeply know his compositional habits. See, for instance, the above-quoted answer of Mozart in regards of Nannerl’s performance of KV 451.

This preference for enriching a rather sketchy (original) notation seems to resonate with contemporary instrumental performance practice; it is essential to considering that a work like the above-mentioned KV 466 Romance was intended for Viennese five or five and half octaves instruments following the Walter-Stein-Streicher line. These pianos have such a rapid sound decay that it is hard to believe they could have matched the texture of the Figure1, in its original configuration. Rather, some sort of ‘filling in’ might have been expected, in order to improve the connections between notes which otherwise would have sounded too detached. Hummel addresses this issue:

The characters indicating the various graces, the appoggiatura both before and after a note, and other embellishments of a similar description, are indispensable in music, as they assist greatly in connecting the notes of the melody, and contribute much towards expression and beauty of performance. As the number of these characters formerly in use, and the slight shades of difference existing between them, often caused them to be neglected or misapplied, and, as in the modern style of writing, many are become altogether unnecessary, and others are indicated to the Player by notes, in order to ensure the correct performance of them.17)See: Johann Nepomuk Hummel: A Complete Theoretical and Practical Course of Instructions on the Art of Playing the Piano Forte. (London, Boosey, 1829), Part III, p. 1: ‘On Graces, and on the characters used to denote these species of minor embellishments’. The correlating passage reads in Ausführliche theoretischpraktische Anweisung zum Pianofortespiel vom ersten Elementar-Unterrichte an bis zur vollkommensten Ausbildung (Wien: Haslinger, 1828), p. 393: ‚Ausschmückungen, Vor, – Nachschläge, und andere Manieren sind in der Musik wegen genauerer Verbindung der Töne, des Zusammenhangs der Melodie, des Nachdrucks, und des guten und schönen Vortrags unentbehrlich; doch, da die frühere grosse Anzahl solcher Zeichen, und ihr oft sehr geringer Unterschied, viele derselben den Schüler vernachlässigen liess, in der neuen Schreibart aber mehr ganz unnöthig wurden, und andere dem Spieler, zur Gewissheit des gewünschten Vortrags, durch Noten vorgezeichnet worden: so scheint mir eine Einschränkung derselben theils nöthig, theils rathsam. (on its footnote:) Will Jemand auch die früher üblich gewesenen Zeichen, wegen des Vortrags der damaligen Komposizionen, kennen lernen, so findet er in ältern Lehrbüchern hinlängliche Erläuterung.‘

Referring to the need for proper connection of notes and melody, Hummel seems to have had a texture like the bare original configuration of Figure 1 in mind, which – in Hummel’s ear – begs for embellishments. The quote is also interesting for the composer’s well-focused account of the evolution of the embellishment practice between the classical and the romantic style: namely, that by the end of the 1820s, the keyboard language had come to include written-out embellishments which provided the performer with every performance detail. This transition, certainly connected with the evolution of technical and aesthetic values, is also an inevitable consequence of the major sociological revolutions of the late eighteenth century which ultimately created a deep separation between composition and performance, and therefore between the composer and the performer. The rise of the middle class created a huge music market demanding detailed performing instructions (particularly for the interpretation of the classical literature) and in this context, the role of composers like Hummel was of crucial importance. In his piano method, again, he explains how this usus componendi had changed, to a state in which every embellishment – even the cadenza of the piano concerto – was provided in the score; about the fermata sign, he states:

The Pause denoting that an extemporaneous embellishment was to be introduced, appeared formerly in concertos &c. generally towards the conclusion of the piece, and under favor of it, the player endeavoured to display his chief powers of execution; but as the Concerto has now received another form, and as the difficulties are distributed throughout the composition itself, they are at present but seldom introduced. When such a pause is met with in Sonatas or variations of the present day, the Composer generally supplies the player with the required embellishment.18)See: Hummel (London, 1829), Part I, p. 66 (footnote); and the correlating passage in Hummel (Wien, 1828), p. 55: ‘Die sogenannte Schlussfermate (Cadenza, Tonfall) kam früher häufig in Konzerten etc. meist gegen Ende eines Stücks vor, und der Spieler suchte in ihr seine Hauptstärke zu entwiekeln. Da aber die Konzerte eine andere Gestalt erhalten haben, und die Schwierigkeiten in der Komposizion selbst vertheilt sind, so gebraucht man sie selten mehr. Kommt noch zuweilen in Sonaten oder Variazionen eín solcher Haupt- Ruhepunkt vor, so giebt der Komponist selbst dem Spieler die Verzierungen‘.

Hummel reveals that by 1828 the piano concerto genre has received ‘another form’ than that of the past. The different textural outfit of classical era, indeed, is fully understandable if we consider also that by Mozart’s time, the piano concerto had still not been established as a fixed musical genre. Another remarkable aspect to take into account is that the publishing world still had to develop the capillary European network, which later came to secure both dissemination of the literature and an income for composers: had a considerable dimension of the audience been reachable by the publishing network, this would definitively have encouraged the composers to a different approach. The classical keyboard concerto was still an occasional musical genre: even a composer like Mozart approached the conception of such a work with no consciousness of its potential ‘eternal musical life’. As far as he or anyone else could comprehend, a concerto would be composed immediately ahead of one set occasion and forgotten soon after its performance in order to make room for a brand new concerto for the next academy. We may therefore claim that during the classical period, the keyboard concerto was a musical genre not meant to be ‘confined’ in the score, but one which was finding a complete definition only during its performance.

Hummel as a mediator between Mozart and us

As long as Mozart’s own performances lack documentation in sound and complete music scores, a witness like Hummel, having been so close to Mozart, is of primary importance. Moreover, it is certainly no understatement that our picture of its performance practice is less reliable than the one diffused at Hummel’s time. For instance, music reviews of the 1820s put the matter in a different perspective entirely, seen with modern eyes. This is what The Literary Gazette reports regarding the problems posed by Mozart piano concertos:

… the pianoforte part, in their original form, being so barren and defective, as to leave nearly on every page blanks of seven or ten bars, where other instruments take up the subjects, but even the little that is written out for the pianoforte not being set as Mozart himself played it. It is a mere skeleton, which his never failing imagination, at the call of the moment, endowed with life and soul.19)This fragment belongs to a review of J. B. Cramer’s arrangements of Mozart piano concertos; see: The Literary Gazette, Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences, & c., London, vol. 437 (June 4th 1825), p. 364.

And the audience’s satisfaction regarding Hummel’s solutions, is clear from this 1827 review of his D minor KV 466 arrangement:

… Genuine melody of the sweetest kind, simple, clear and perfect in its rhythm, abounds every where. The ‘Romanza’, for instance – what softness, what intensity of musical feeling! And all this is achieved at the least possible expense of notes. As Mozart himself said once, there is not one too many!20)The Repository of Arts, Literature, Fashions, Manufactures, & c., London, vol. 10 (October 1st 1827), pp. 236-37.

Indeed, Hummel’s affinity with Mozart’s musical language went back a long way. It began in 1786, when the very young Johann Nepomuk was accommodated in the Mozart family home for about two years. Here, the young musician participated in the public and private life of the composer, coming into direct contact with all the works that saw light during those years, which were indisputably among the most fertile of Mozart’s whole career. Hummel’s interest in, and deep knowledge of his teacher’s works for fortepiano and orchestra is attested by numerous accounts: apart from witnessing the birth of several of the masterpieces of those years, Hummel must himself have studied these pieces on more than one occasion with his teacher, giving public performances of them in his presence.21)See Gerhard Bachleitner, ‘Mozart-Metamorphosen. Zu Johann Nepomuk Hummels Bearbeitungen Mozartscher Klavierkonzerte’, in Acta Mozartiana, 44-46 (1997-99), pp. 17-28; see also: Miucci, ‘I Concerti per fortepiano’, pp. 92-6. As the 1830s approached, Hummel was enjoying great fame as a pianist, composer and teacher – not the least, one might say, owing to his close association to the Mozartian tradition. This reputation undoubtedly derived mainly from his pianism, as expressed by his aesthetic choices and approach to the instrument — qualities that were perceived by Viennese musical society during those years as standing in opposition to the muscular pianism of Beethoven, which likewise had its admirers in the Austrian capital.

Hummel’s English intermediary for his many publications was J. R. Schultz, a ‘music dealer’ of whose life little is known.22)He is probably John Reinhold Schultz; see Alan Tyson, ‘J. R. Schultz and His Visit to Beethoven’ in The Musical Times, 113 (1972), pp. 450–51. Regarding Mozart’s piano concertos, Schultz initially suggested to the composer a series of 12 transcriptions, but in fact, for reasons connected with the publisher or presumably because of the incidental death of the arranger, the project ceased after only seven works had appeared: no. 1 in D minor, KV 466; no. 2 in C major, KV 503; no. 3 in E flat major, KV 365/316a; no. 4 in C minor, KV 491; no. 5 in D major, KV 537; no. 6 in E flat major, KV 482; and no. 7 in B flat major, KV 456.23)See Joel Sachs, ‘Authentic English and French Editions of J. N. Hummel’ in Journal of American Musicological Society, 25/2 (1972), pp. 203-29 and Joel Sachs, ‘A checklist of the works of Johann Nepomuk Hummel’ in Notes. The Quarterly Journal of the Music Library Association, 30 (1973), pp. 732-54. All these arrangements were conceived for fortepiano solo, with the accompaniment of flute, violin and cello. The participants in this venture into simultaneous publication were Chappell for the English market (London) and Schott for the French and German markets (Paris, Mainz and Antwerp).24)While the negotiations between Hummel and Schultz for the setting up of this project go back to the first half of the 1820s, the evidence of the autograph manuscripts suggests that Hummel wrote these transcriptions between the second half of the 1820s and the year 1836. These are the arrangements giving a compositional date on the manuscript: KV 365 (August 1829), KV 456 (January 1830), KV 491 (1830), KV 537 (March 1835) and KV 482 (January 1836).

Preparing a modern edition

The editing of the first work in the collection of arrangements, the famous concerto in D minor KV 466, (released in June 2013) did not pose particular or peculiar difficulties; the two printed sources (Chappell and Schott, hereafter P1 and P2) presented only in some cases discordances, mainly in terms of articulation, dynamic and phrasing marks (with the exception of a few obvious diastematic mistakes). As far as the piano part is concerned, P2 followed P1 in its layout of the bars on all pages. This leads one to think that the first one took the plates of the second one as its model. However, the other three parts have different pagination. Different is the situation with regard to the manuscript source – the Hummel autograph (held in the British Library, Add. MS 32 234) – hereafter MS:25)The transcriptions of the concertos KV 466, 503, 491, 537, 482 and 456 are found in the volume Add. 32,234, while KV 365/316a is divided between two volumes: Add. 32,227 (ff. 89–94) and Add. 32,222 (ff. 107–32). See Miucci, ‘I Concerti per fortepiano’, p. 125. in general, it was not always useful for textual analysis, since it lacks several bars, particularly in the solos at points in which it was planned to leave Mozart’s text unaltered. This is a peculiarity only for this first concerto and it is plausibly due to the rush with which Hummel and/or the publisher intended to release this first issue. The manuscript stage must have been a first draft of the transcription, the arranger evidently intending for the copyist to refer to entire bars of the Mozart source he used: Hummel must certainly have consulted one of the editions in circulation at the time, either Artaria (1796), André (1796/1809) or Breitkopf & Härtel (1802), but there is no evidence that he consulted Mozart’s autograph manuscript.

MS contains only very few marks of articulation, dynamic level and phrasing, all of which Hummel clearly planned to add during the later stages of the publication process. This habit, as it will be better explained below with regard to the KV 456 concerto, is common with all the other six concertos arranged by Hummel, and in more than one circumstance it created important editorial difficulties in those spots where the two printed sources passed on different versions. When, as was often the case, MS gave no clues in this respect, it was equally impossible to rely in toto on the Mozartian original: Hummel’s new scoring did require certain alterations – in particular concerning marks of articulation, dynamics and phrasing. In addition to taking the opportunity to avail of the expressive means afforded by modern instruments, the arranger needed to make further changes of these kinds on account of the new sonorities and tone colours associated with the medium of the piano quartet; finally, he must have been influenced to some extent by the modern pianistic idiom, which, since Mozart’s time, had developed in both aesthetic and technical respects.

In the case of this first concerto, MS did not really help to clarify the precise composition date of the arrangement, nor textual discordances; on the other hand it offered precious hints, useful for a deeper understanding of the poetics and aesthetic adopted by Hummel in his task.26)It was unfortunately difficult at the present moment to date the arrangements of this first concerto with any great precision. There is no indication of date on the manuscript, and this opening publication was not registered at Stationers’ Hall; however, it must have come out by September 1827, since an announcement of this edition was made to the English public in the Repository of Arts for 1 October 1827 (see: The Repository of Arts, Literature, Fashions, Manufactures, & c., London, vol. 10 (1 October 1827), pp. 236–37). For example, it is interesting to look at the incipit of the first movement and the relative steps of its elaboration, accomplished by the composer in order to render the original rhythmical construction in the most efficient way. As can be seen in the reproduction of this first manuscript page (Figure 3), Hummel never considered reproducing the syncopated figuration, typical of this concerto, in the piano part – assigning it only to the violin. Actually his priority, on the contrary, seems to have been to guarantee a certain rhythmic stability and inflexibility: provisionally, he decided to create a piano part with a left hand providing an entirely regular rhythm through a third interval eighth-note pattern and a right hand reproducing the strings’ melody line but normally not in syncopated figuration. Realizing that this solution would probably not have guaranteed enough balance and rhythmical stability, Hummel switched to a new figuration: the left hand doubling the very important and rhythmically characterized triplet figuration of the cellos and doubles basses, while the right hand stresses further the rhythmic regularity through the repetition of an eighth-note dyad. Hummel must have found this solution more appropriate for providing enough freedom to the violin player, allowing a proper reinstatement of the typical ‘rubato’ effect – not what it might seem like a mere syncopation – originally obtained from the contraposition of the high and low string sections.

Figure 3 Hummel’s manuscript, arrangement of the Mozart Piano concerto in D minor, KV 466, ‘Allegro’. London, British Library, Add. MS 32 234, f 100r, bars 1-18.

It seems to this author that Hummel tried to return the Mozartian message, searching consequently for the most efficient way to translate it from the typical orchestral language to the actual chamber dimension. Comparing for example, the same spot (Figure 4a) arranged by another important piano composer of the time, Johann Baptist Cramer (Figure 4b), it is interesting to notice how the two composers intended and translated differently its meaning: for Cramer, indeed, the most important element to return seemed to be the syncopated figuration, assigned to all the instruments. Nevertheless, the result is that the original effect of this kind of writing, namely the direction of the musical phrasing always going forward, is somewhat missing; this is due to not having the typical tone blend of a string orchestra. On the contrary, the Hummel version, as explained before, guaranteeing that the violin line has the possibility to be inserted freely, reproduces more accurately the intended phrasing inherent in this kind of syncopated figuration.27)See Miucci, ‘I Concerti per fortepiano’, pp. 104-05.

The duty and attitude of a modern editor

Compared to the relatively unproblematic task of editing the D minor, the situation concerning the piano concerto in B flat major KV 456, released in 2014,28)The choice to publish it as the second issue of this collection (it was actually released as the last one in Hummel’s plan) is related to the fact that this concerto, together with the D minor KV 466, has just been recorded, for the first time on historical instruments, and will appear on the CD label Dynamic (www.dynamic.it). is entirely different; aspects of dating, manuscript completeness and other circumstances affect the final editorial decisions and raise the question of the editor’s role. Even though it was the fourth concerto that Hummel transcribed (indeed, a date of January 1830 is inscribed on the manuscript), it was published last, after all the previous six issues had been directly supervised by Hummel during his lifetime (the composer died in October 1837). Dating this edition with great accuracy is of crucial importance in regard to textual criticism: the salient problem with this concerto is that P1 and P2 appear to be substantially incomplete too, just like MS, with regard to articulation, phrasing and dynamic marks. This incompleteness might be explained by the fact that we have no evidence that the arranger was able to inspect the proofs during his lifetime, so it was probably published as a posthumous edition: since it was not registered at Stationers’ Hall, the only evidence we have of its publication is a review that appeared in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung in 1842, five years after Hummel’s death.29)Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, Leipzig, vol. 12 (23 March 1842), pp. 251–52. The early 1840s seems to be a plausible date, also taking into account the plate number of the Schott edition (n. 6033).30)See Otto Erich Deutsch, Music Publishers’ Numbers: A Selection of 40 Dated Lists, 1710–1900 (London: Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux, 1946), p. 21. Final confirmation of this supposition comes from the entry for this concerto in Friedrich Hofmeister’s catalogue: this gives the publication year as 1841, therefore it is in line with the above-mentioned review, which appeared a few months later in the AMZ.31)http://www.hofmeister.rhul.ac.uk

It is interesting in this sense to notice that in 1838, one year after Hummel’s death, his widow Elisabeth published an advertisement, addressed to all categories of music lovers (publishers, performers, amateurs, etc), in the main musical periodicals, in order to make known the huge amount of manuscript music left by her husband. With regard to this, we read in The Musical World:

An announcement signed ‘Betty Hummel’, has appeared in the German musical journals, and makes known that the late Hof-Kapellmeister, the Chevalier John Nepomuk Hummel (such are the style and titles of the illustrious deceased) has left behind him a considerable quantity of manuscripts, which his widow is desirous to dispose of. Among these will be found many compositions for the pianoforte, several concertos for the piano, as well as for the other instruments, many songs, cantatas, masses, overtures, and instrumental music of various kinds. It is impossible to read of these posthumous works without pleasurable anticipation. We would willingly snatch from the tomb every honourable relique of the mind of one who has left a void in the world of composition, but we are rather puzzled to conceive how a man of Hummel’s solid reputation, with a ready sale for every thing he chose to write, but who published of late at distant intervals only, should keep so much by him in manuscript if he ever designed it to appear. Death may indeed have frustrated his intentions. On the other hand we have misgivings of injury to the dame of a composer by too hasty a ransacking of his crypts and cabinets, and indiscriminately communicating to the public whatever might be found there. The performance of this duty towards the deceased composer, requires the highest judgment and delicacy, and we hope it will be committed to the superintendence of an able musician.32)The Musical World, London, vol. 140 (15 November 1838), pp. 157-158.

Unfortunately no list of these unpublished manuscript compositions available in the Hummel’s library has survived. But this fragment seems to confirm the speculation that the collection of arrangements of Twelve Grand Concertos stopped because of the composer’s death.33)The title page of the Chappell edition reads thus: ‘Mozart’s | Twelve | Grand Concertos, | arranged for the | Piano Forte, | and Accompaniments of | Flute, Violin & Violoncello, | including | Cadences and Ornaments, | expressly written for them by the celebrated | J. N. Hummel | of Vienna. | NB. These Concertos are Arranged for the Piano Forte from C to C’. The Schott edition omitted the concluding remark, since the mentioned compass (CC-c’’’’), conforming to contemporary English instruments, differed from that of their Viennese counterparts, which had a compass typically lying a fourth higher (FF-f’’’’).

At the same time, it is interesting to read of their ‘hope’ of leaving the considerable editorial tasks to ‘the superintendence of an able musician’. Unfortunately, it seems on the contrary, that the destiny confined to the first edition of this KV 456 arrangement was the opposite of what was desired. Plausibly, either one of the two publishers (Chappell and Schott) or some other figure involved in this project might have bought the manuscript from Elisabeth Hummel and published it, following rigidly this source, bar a few exceptions. The publishers – presumably motivated to print and sell the popular arrangements as soon as possible – did not, unfortunately, consider how much more complete the printed editions of the six previous issues were ironically creating a similar situation to that of the original Mozartian output. This circumstance would easily explain the similarly unusual incompleteness between MS, P1 and P2. As anticipated beforehand, if we consider the fact that Hummel customarily left the initial (manuscript) stage of the draft in a highly incomplete state, especially with regard to dynamics and marks of phrasing and articulation – all of these being details for addition at later stages of the publication – the two printed sources (P1 and P2) appear strangely deficient in that respect. As a consequence, there comes a heavy and difficult question to answer: what is the duty and attitude of a modern editor in such a case? Should he continue to provide researchers and performers with the same text, which has previously been published without the composer’s supervision, based on incorrect suppositions (leaving the responsibility up to anybody to complete) or should he try to propose and provide a concrete answer for this incompleteness? In this modern edition of KV 456, it has been considered appropriate to opt for a solution that would guarantee, in accordance with philological criteria, a text compatible with a coherent and historically informed performance practice. Therefore, not having a disposable digital output, it has been decided to preserve the original form of the text, as handed down by all the sources, but, exceptionally, supplemented here by numerous additions, especially regarding phrasing and dynamics. These are all easy to distinguish, being either dashed (slurs) or enclosed in square brackets (articulation marks) or printed in smaller characters (dynamic marks). The choice of these additions has been made based on a thorough investigation of Mozart’s original text and of the compositional approach adopted by Hummel for the other concertos.

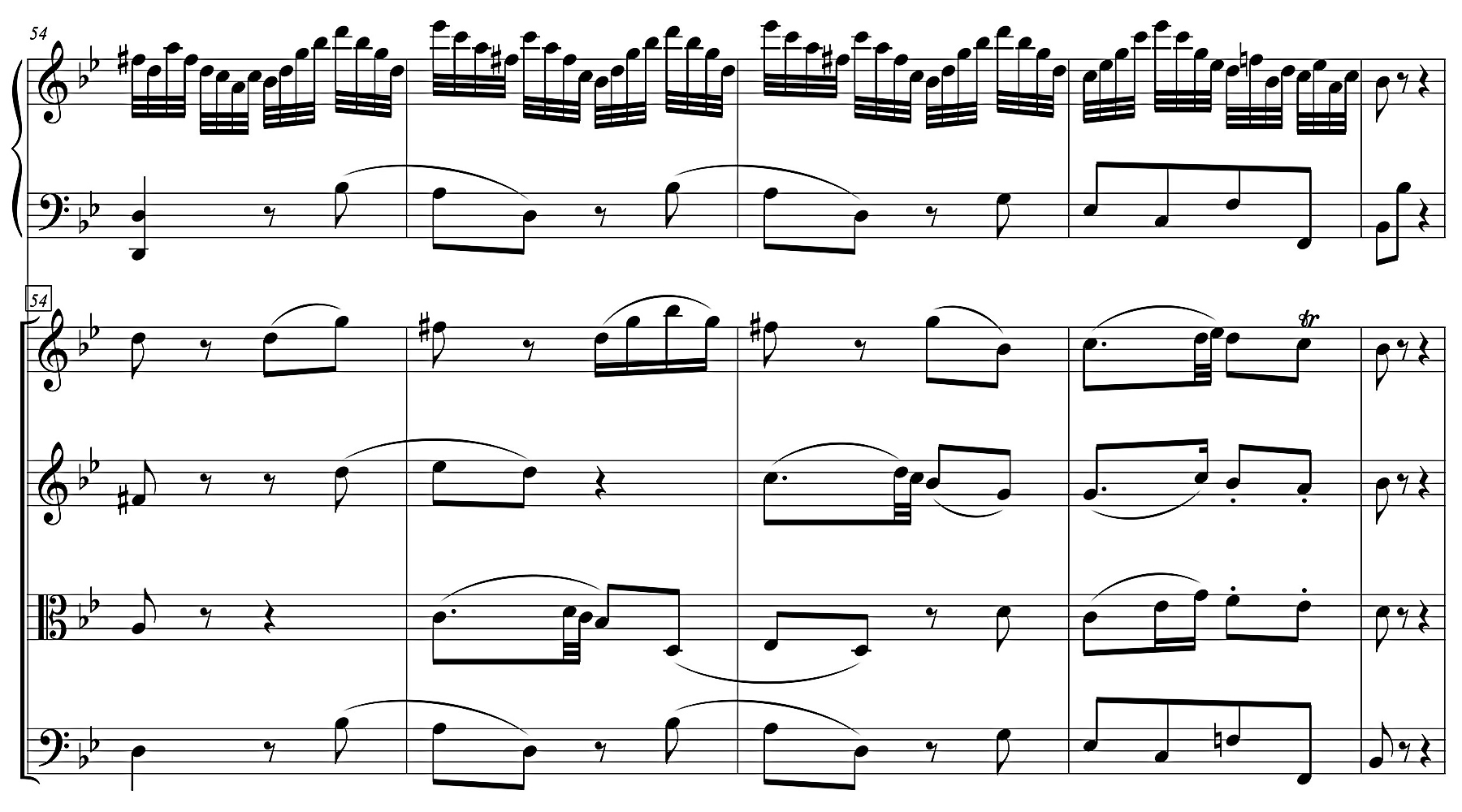

For example, look at the re-exposition in the violin part of the main theme in the second movement (bars 51-57). Several slurs were missing (also in the cello part) for no obvious reason, either of expression or articulation (Figure 5a gives Hummel’s arrangement, whereas Figure 5b shows Mozart original version). While in this case, nowhere in this movement does MS provide a slur on a semiquaver’s figuration (bar 55), sometimes PP1 and PP2 are consistent with the original Mozartian text, indicating the proper articulation’s direction (as, for example, in bar 5). For this reason it has been considered appropriate to indicate this in the score and parts, with a dotted slur. This same excerpt is interesting also with regard to the modifications and additions made by Hummel to the keyboard part. The slow movement of the KV 456 presents a little less problematic situation than many other concertos (like the KV 466) in this sense: the original pianistic texture, indeed, seems to be slightly more elaborated and fulfilled. Nevertheless, in the middle thematic elaboration (at bars 51-57 and at bars 72-83, which would be typical ‘skeleton moments’, as the theme is assigned to the strings and the piano an accompanying role), Hummel decided to modify the piano accompaniment, which has a particularly stressed rhythmical support, increasing its brilliancy: Mozart, indeed, assigned a figuration of hemidemisemiquavers while Hummel diminished it by using a figuration of hemidemisemiquaver triplets. Though it is difficult to state with a certainty whether this kind of modification was prompted by a ‘free’ choice of the arranger or whether it was a recollection of one of his teacher’s performances, it certainly seems coherent with those virtuoso values belonging both to the Biedermeier and romantic era, as well as to the classical performance practice, which, as I have attempted to show, tolerated considerably greater variety and ambiguity than what has previously been gathered.

Conclusion

Modern musicology’s increasing interest in the ‘student’s generations’ that follow major composers, offers an opportunity to investigate works and pieces of information that may prove welcome additions to our understanding of the larger picture. The study of this historical teaching process provides precious information, for example relating to performance practice for the works of such important figures as Chopin and Beethoven. Unfortunately, the evidence related to the generation that dealt with Mozart is less conspicuous, in terms of both quantity and quality. With this in mind, a largely neglected source like these arrangements by Hummel, are published in the conviction that it will be worthy of the interest of performers and researchers alike.

Footnotes

References

| ↑1 | I am indebted to Bianca Maria Antolini, Thomas Gartmann, Anselm Gerhard, Christina Kobb and Giorgio Sanguinetti for various suggestions in the preparation of this article. Thanks also to Rachel Deloughry for her assistance with the English editing of earlier drafts. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | On this topic, see: Christopher Hogwood, ‘Urtext, que me veux-tu?’ in Early Music, 41/1 (2013), pp. 123-27. |

| ↑3 | The Literary Gazette, Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences, & c., London, vol. 437 (June 4th 1825), p. 364. For the full quote, see the text preceding footnote 19 below. |

| ↑4 | This seven-concerto collection, released by the British publisher Edition HH (http://www.editionhh.co.uk/) is edited with the valuable collaboration of Costantino Mastroprimiano and with the precious support of the Research Department of the Hochschule der Künste of Bern (http://www.hkb-interpretation.ch). The first issue, KV 466, was released in June 2013 while the second one, KV 456, in February 2014 and KV 503, in September 2015. This collection is only one of the outputs of a research project called ‘Beethovens «Fantasie» – Between composition and music theory, improvisation and performance practice of piano players around 1800’. This research project led to the international Symposium «Improvisieren – Interpretieren», which took place in Bern HKB in October 2013 and whose papers will be soon published by Argus.(http://www.hkb.bfh.ch/en/research/forschungsschwerpunkte/fspinterpretation/veranstaltungen/improvisieren/ |

| ↑5 | Indeed, KV 413-415 were sold in manuscript copies. They were published by Artaria in Wien in 1785 and Mozart, famously, had written to his father (28 December 1782) that ‘Die Concerten sind eben das Mittelding zwischen zu schwer, und zu leicht – sind sehr Brilliant – angenehm in die Ohren – Natürlich, ohne in das leere zu fallen – hie und da – können auch Kenner allein Satisfaction erhalten – doch so – daβ die nichtkenner damit zufrieden seyn müssen, ohne zu wissen warum‘. |

| ↑6 | For example, André released in 1792, as first editions, the concertos KV 271, 449 and 456. |

| ↑7 | See Friedrich Rochlitz, ‘Anekdoten aus Mozarts Leben’, in Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, 1 (1798), p. 113. |

| ↑8 | The reader is referred to the extensive literature on the subject: Eva and Paul Badura-Skoda, Mozart- Interpretation, (Wien: Edward Wancura Verlag, 1957); Frederick Neumann, Ornamentation and Improvisation in Mozart (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986); Robert D. Levin, ‘Instrumental Ornamentation, Improvisation and Cadenzas’, in Performance Practice, Music after 1600, ed. by H. Mayer Brown and S. Sadie (New York: Norton, 1990) pp. 267–91; Philip Whitmore, Unpremeditated Art: The Cadenza in the Classical Keyboard Concerto (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991); Christoph Wolff, ‘Cadenzas and Styles of Improvisation in Mozart’s Piano Concertos’ in Perspectives on Mozart Performance, ed. by L. Todd (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991) pp. 228-38; Robert D. Levin, ‘Improvised Embellishments in Mozart’s Keyboard Music’ in Early Music 20 (1992), pp. 221–34; David Grayson, ‘Whose Authenticity? Ornaments by Hummel and Cramer for Mozart’s Piano Concertos’ in Mozart’s Piano Concertos: Text, Context, Interpretation, ed. by N. Zaslaw (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996) pp. 373–91; Leonardo Miucci, ‘I Concerti per fortepiano di Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: le trascrizioni di Johann Nepomuk Hummel’ in Rivista Italiana di Musicologia, 43/45 (2008), pp. 81–128. |

| ↑9 | Letter of 9 June 1784, see: NMA, V/15/5, p. 208 |

| ↑10 | (‚wenn ich dieses Concert spielle, so mache ich allzeit was mir einfällt‘), in Mozart Briefe und Aufzeichnungen, 243, 22 January 1783. |

| ↑11 | See: Daniel Gottlob Türk, Clavierschule, oder Anweisung zum Clavierspielen (Leipzig and Halle: Schwickert, 1789). Such a performance practice, indeed, is traceable as well in several other treatises conceived for different instruments than keyboard; see, for instance, Quantz’s and Tartini‘s examples: Johann Joachim Quantz, Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversière zu spielen, (Berlin: Voβ, 1752); with regard to Tartini, a new critical edition of the complete theoretical and didactic works is about to be released, published by SEdM (www.sedm.it) and edited by M. Canale. |

| ↑12 | See: NMA edition of KV 488 (V/15/7), KB pp. g/10-4 and g106-09. |

| ↑13 | Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Mus. Ms. 15,486/5. |

| ↑14 | See, for example: Neumann, Ornamentation and improvisation, pp. 247, 251-53. |

| ↑15 | See: Robert D. Levin, ‘K. 488: Mozart’s Third Concerto for Barbara Ployer?’, in Mozartiana. The Festschrift for the Seventieth Birthday of Professor Ebisawa Bin, (2001), pp. 555-70. |

| ↑16 | In this respect, Mozart did not even trust his sister, who was supposed to deeply know his compositional habits. See, for instance, the above-quoted answer of Mozart in regards of Nannerl’s performance of KV 451. |

| ↑17 | See: Johann Nepomuk Hummel: A Complete Theoretical and Practical Course of Instructions on the Art of Playing the Piano Forte. (London, Boosey, 1829), Part III, p. 1: ‘On Graces, and on the characters used to denote these species of minor embellishments’. The correlating passage reads in Ausführliche theoretischpraktische Anweisung zum Pianofortespiel vom ersten Elementar-Unterrichte an bis zur vollkommensten Ausbildung (Wien: Haslinger, 1828), p. 393: ‚Ausschmückungen, Vor, – Nachschläge, und andere Manieren sind in der Musik wegen genauerer Verbindung der Töne, des Zusammenhangs der Melodie, des Nachdrucks, und des guten und schönen Vortrags unentbehrlich; doch, da die frühere grosse Anzahl solcher Zeichen, und ihr oft sehr geringer Unterschied, viele derselben den Schüler vernachlässigen liess, in der neuen Schreibart aber mehr ganz unnöthig wurden, und andere dem Spieler, zur Gewissheit des gewünschten Vortrags, durch Noten vorgezeichnet worden: so scheint mir eine Einschränkung derselben theils nöthig, theils rathsam. (on its footnote:) Will Jemand auch die früher üblich gewesenen Zeichen, wegen des Vortrags der damaligen Komposizionen, kennen lernen, so findet er in ältern Lehrbüchern hinlängliche Erläuterung.‘ |

| ↑18 | See: Hummel (London, 1829), Part I, p. 66 (footnote); and the correlating passage in Hummel (Wien, 1828), p. 55: ‘Die sogenannte Schlussfermate (Cadenza, Tonfall) kam früher häufig in Konzerten etc. meist gegen Ende eines Stücks vor, und der Spieler suchte in ihr seine Hauptstärke zu entwiekeln. Da aber die Konzerte eine andere Gestalt erhalten haben, und die Schwierigkeiten in der Komposizion selbst vertheilt sind, so gebraucht man sie selten mehr. Kommt noch zuweilen in Sonaten oder Variazionen eín solcher Haupt- Ruhepunkt vor, so giebt der Komponist selbst dem Spieler die Verzierungen‘. |

| ↑19 | This fragment belongs to a review of J. B. Cramer’s arrangements of Mozart piano concertos; see: The Literary Gazette, Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences, & c., London, vol. 437 (June 4th 1825), p. 364. |

| ↑20 | The Repository of Arts, Literature, Fashions, Manufactures, & c., London, vol. 10 (October 1st 1827), pp. 236-37. |

| ↑21 | See Gerhard Bachleitner, ‘Mozart-Metamorphosen. Zu Johann Nepomuk Hummels Bearbeitungen Mozartscher Klavierkonzerte’, in Acta Mozartiana, 44-46 (1997-99), pp. 17-28; see also: Miucci, ‘I Concerti per fortepiano’, pp. 92-6. |

| ↑22 | He is probably John Reinhold Schultz; see Alan Tyson, ‘J. R. Schultz and His Visit to Beethoven’ in The Musical Times, 113 (1972), pp. 450–51. |

| ↑23 | See Joel Sachs, ‘Authentic English and French Editions of J. N. Hummel’ in Journal of American Musicological Society, 25/2 (1972), pp. 203-29 and Joel Sachs, ‘A checklist of the works of Johann Nepomuk Hummel’ in Notes. The Quarterly Journal of the Music Library Association, 30 (1973), pp. 732-54. |

| ↑24 | While the negotiations between Hummel and Schultz for the setting up of this project go back to the first half of the 1820s, the evidence of the autograph manuscripts suggests that Hummel wrote these transcriptions between the second half of the 1820s and the year 1836. These are the arrangements giving a compositional date on the manuscript: KV 365 (August 1829), KV 456 (January 1830), KV 491 (1830), KV 537 (March 1835) and KV 482 (January 1836). |

| ↑25 | The transcriptions of the concertos KV 466, 503, 491, 537, 482 and 456 are found in the volume Add. 32,234, while KV 365/316a is divided between two volumes: Add. 32,227 (ff. 89–94) and Add. 32,222 (ff. 107–32). See Miucci, ‘I Concerti per fortepiano’, p. 125. |

| ↑26 | It was unfortunately difficult at the present moment to date the arrangements of this first concerto with any great precision. There is no indication of date on the manuscript, and this opening publication was not registered at Stationers’ Hall; however, it must have come out by September 1827, since an announcement of this edition was made to the English public in the Repository of Arts for 1 October 1827 (see: The Repository of Arts, Literature, Fashions, Manufactures, & c., London, vol. 10 (1 October 1827), pp. 236–37). |

| ↑27 | See Miucci, ‘I Concerti per fortepiano’, pp. 104-05. |

| ↑28 | The choice to publish it as the second issue of this collection (it was actually released as the last one in Hummel’s plan) is related to the fact that this concerto, together with the D minor KV 466, has just been recorded, for the first time on historical instruments, and will appear on the CD label Dynamic (www.dynamic.it). |

| ↑29 | Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, Leipzig, vol. 12 (23 March 1842), pp. 251–52. |

| ↑30 | See Otto Erich Deutsch, Music Publishers’ Numbers: A Selection of 40 Dated Lists, 1710–1900 (London: Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux, 1946), p. 21. |

| ↑31 | http://www.hofmeister.rhul.ac.uk |

| ↑32 | The Musical World, London, vol. 140 (15 November 1838), pp. 157-158. |

| ↑33 | The title page of the Chappell edition reads thus: ‘Mozart’s | Twelve | Grand Concertos, | arranged for the | Piano Forte, | and Accompaniments of | Flute, Violin & Violoncello, | including | Cadences and Ornaments, | expressly written for them by the celebrated | J. N. Hummel | of Vienna. | NB. These Concertos are Arranged for the Piano Forte from C to C’. The Schott edition omitted the concluding remark, since the mentioned compass (CC-c’’’’), conforming to contemporary English instruments, differed from that of their Viennese counterparts, which had a compass typically lying a fourth higher (FF-f’’’’). |