The choral sublime:

a study of Beethoven’s Drei Equale

Table of Contents

Sebastiaan Kemner

Sebastiaan Kemner is currently a DPhil candidate at the University of Oxford, and is also a Professor of trombone at the Royal Conservatoire in The Netherlands. He is a freelance solo and chamber musician, and has played with numerous orchestras, such as the Berlin Philharmonic and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra.

by Sebastiaan Kemner

Music & Practice, Volume 8

Scientific

On Thursday 29 March 1827, the streets of Vienna were filled with people who had come to pay their final tributes to Ludwig van Beethoven, who had passed away three days earlier. After the appropriate prayers were said and a hymn was sung, an elaborate funeral procession left Beethoven’s home to accompany the coffin to the nearby Church of the Holy Trinity. Among the procession were priests, poets, actors, composers, musicians, students and an impressive group of notables. They were beautifully adorned in black clothes, carrying torches, white ribbons and lilies.[1] The procession was accompanied by four trombone players and 16 male singers performing two of Beethoven’s Drei Equale. Ignaz von Seyfried, Kapellmeister at the Theater an der Wien at the time, had adapted the first and third movements to the text of the Miserere (Psalm 51, the first and the second verse) especially for this occasion. The solemn tones of the trombones and the choir filled the streets of Vienna as the procession made its way through the crowds (estimates vary between 10,000 and 30,000 spectators).[2]

Drei Equale

These two movements of the Drei Equale (WoO 30, 1812) (the first and the third) were first published a few months later, under the name Trauer-Gesang, in the arranged version for trombones and male choir by Ignaz von Seyfried that had been performed at the funeral.[3] In the foreword to the first edition, the events leading up to the performance of the pieces at the funeral are briefly detailed:

Als nun der Morgen des 26. Märzes 1827 keinen Zweifel mehr übrig liess, dass der drohende Verlust nur allzunahe, ja unvermeidbar sey, begab sich Hr. Haslinger mit diesem Manuscripte zu Herrn Capellmeister von Seyfried, um mit demselben die Möglichkeit zu besprechen, aus diesen Equale’s *) zu den Worten des Miserere einen Choral-Gesang zu bilden, und somit die irdischen Reste unseres Tonfürsten unter den Trauerklangen einer seiner eigenen Schöpfungen zur ewigen Ruhe zu begleiten. Herr von Seyfried ging nach genauer Prüfung der Reliquie in diese Idee ein, und unverzüglich an die Arbeit selbst, welche auch, da Abends um 6 Uhr die Natur ihr Eigenthum bereits zurück forderte, noch in der nächstfolgenden Nacht beendigt ward.

*) Welche nun auch bey Tob. Haslinger erschienen sind.[4]

When, on the morning of the 26th of March 1827, no doubt remained that the impending loss was now all too near, and even inevitable, Mr. Haslinger took these manuscripts to Capellmeister von Seyfried, to discuss with him the possibility of making from these Equale *) a Choral-Gesang on the words of the Miserere, in order to accompany the earthly remains of our ‘Prince of Music’ to their eternal resting place amidst the mournful sounds of one of his own compositions. After an accurate examination of the relics Mr. Seyfried agreed to this idea, and he set about his task without delay, which, since that evening at 6 o’clock nature had already reclaimed its property, was finished the following night.

*) Which are now also published by Tob. Haslinger.

Over the years, Beethoven’s Drei Equale have made their way to the core of the trombone quartet repertoire, which is not surprising considering the dearth of pieces by prominent composers for this particular genre. The performance of the Drei Equale at Beethoven’s funeral, as described above, brought the pieces some notoriety outside of the trombone world, and they are regularly mentioned in accounts and discussion concerning Beethoven’s death. However, there has been little scholarly research on the Drei Equale themselves. When they are touched on slightly more in depth, they are generally not referred to as the highpoint of Beethoven’s oeuvre: because of their plainness, shortness, and unusual scoring, they are often regarded as incidental pieces with not much artistic or aesthetic value. But if these pieces really are so mediocre, then why were they chosen to be performed at the funeral of one of the greatest composers in history? Was this choice merely the result of a coincidence, or of a longstanding funeral tradition, or is it possible that there is more to the Drei Equale than meets the eye?

The traditional use of the trombone and its historical allusions or topoi were still widely known and accepted in the beginning of the nineteenth century. In this article I will consider their effect on Beethoven’s writing for the instrument – in the Drei Equale, but also in his symphonies. I will continue to examine the relationship between Beethoven’s use of the trombone and his sublime style (the Romantic notion of immeasurability, often attributed to Beethoven’s music, and of which his symphonies are considered the summit). Finally, an analytical approach to the Drei Equale will uncover whether the sublime can be found in these pieces, too.

Figure 1 A depiction of Beethoven’s funeral by Franz Stöber (1827). In the bottom left corner four trombone players can be seen. (Franz Stöber, ‘Beethovens Leichenzug vor dem ehemaligen Schwarzspanierkloster in Wien’, 1827. Watercolour on paper, 41,2 by 59,0 cm. Accessed March 15, 2018. http://www.lvbeethoven.com/Bio/BiographyFuneralOration.html.)

The voice of God

The choice of four trombones for Beethoven’s funeral might seem surprising, but it can be linked to an old tradition of using the trombone for occurrences related to matters of death and divine presence. Examples can be found throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in pieces by Schütz, Bach, Gluck and Mozart, among others, where the trombones are used to accompany moments of divine intervention or references to the afterlife. One possible explanation of this phenomenon stems from Martin Luther’s Bible translation (1534). He translates both the Hebrew word ‘shofar’ (שׁוֹפָר) and the Greek ‘salpigx’ (Σάλπιγξ) as ‘Posaune’, the German word for trombone. Stewart Carter notes this, writing: ‘In the Old Testament, many references to the shofar are associated with solemn pronouncements of the Lord, while in Revelations the salpigx heralds the Last Judgment. Thus, for readers of Luther’s Bible, the trombone was akin to the voice of God, and Lutheran composers exploited this association quite effectively’.[5] In the King James Bible, on the other hand, both terms are translated as trumpet, which could explain why there does not seem to be a similar allusion in British musical history, and maybe even why the trombone was so much less popular in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Britain than it was in the German speaking world. On the other hand, this would not explain why a similar use of the trombone can be found in the music of Catholic composers, for instance in the opera L’Orfeo (1607) by Claudio Monteverdi, an Italian Catholic, in which trombones are used to accompany scenes set in the Hades, and in Mozart’s Requiem (1791), a Roman Catholic mass for the dead, in which the trombone signals the Last Judgement.

Monteverdi’s writing could very well be a product of a catholic tradition going back to the beginning of the sixteenth century, which involved trombone players reinforcing choral performances in Italian churches.[6] Sources show that, in the course of the century, more and more trombone players are hired by catholic churches, making performances in religious settings one of the main functions for the trombone at the time.[7] Trevor Herbert notes that ‘the suitability of trombones (and cornetts) for doubling voices derived from the instruments’ dynamic and expressive versatility, and their capacity to adapt to different intonations’.[8] Indeed, the trombone was one of the few wind instruments which was really suited for playing with voices, also because of its capability to perform a proper chromatic scale over a large range. In this tradition, the trombone’s later reputation as a divine instrument is already foreshadowed. With this musical allusion established in both the Catholic and the Lutheran tradition, it is not surprising that the trombone remained associated to religion and afterlife for centuries to come. The widespread use of trombone obligato parts in Viennese oratorio that blossomed in the eighteenth century is very likely to be a product of this tradition as well,[9] which makes Mozart’s choice of having a trombone play the solo in the ‘Tuba Mirum’ of his Requiem all the more understandable.

The trombone continued to be used as a church instrument, and for a long time it did not find its place in serious secular music. Indeed, in 1785 the noted German poet, journalist and composer Christian F. D. Schubart wrote: ‘Ausgemacht aber ist es, dass der Posaunenton ganz für die Religion und nie fürs Profane gestimmt ist’ (But it is certain that the sound of the trombone is entirely intended for religion and not for secular use).[10] In his book on musical allusions, Christopher Reynolds talks about ‘the “expressive vocabulary” of musical topics, a world … of musical types and styles that eighteenth- and nineteenth-century composers shared with their audiences’.[11] Composers and audiences of the beginning of the nineteenth century, including Beethoven himself, would still have been sufficiently familiar with this ‘vocabulary of musical topics’ to associate a solemn trombone chorale with some sort of heavenly presence.

All Souls’ Day

In order to determine if these topical allusions are also present in the Drei Equale, it is important to take a closer look at the circumstances surrounding their composition. Seyfried describes the origin of the Drei Equale as follows:

Als L. van Beethoven im Herbste des Jahres 1812 seinen damahls in Linz als bürgerl. Apotheker ansässigen Bruder besuchte, wurde er von dem dortigen Dom-Capellmeister Herrn Glöggl freundschaftlich angegangen, ihm für den Aller-Seelen-Tag (den 2. November) sogenannte Equale für 4 Posaunen zu componiren, um solche herkömmlicher Weise an diesem Feste von seinen Musikern abblasen zu lassen. – Beethoven zeigte sich bereitwillig dazu; er entwarf wirklich zu diesem Zwecke drey zwar kurze, aber durch die Grossartigkeit der Anlage die Meisterhand beurkundende Sätze.[12]

When, in the autumn of the year 1812, L. van Beethoven visited his brother, who was then resident in Linz and a Pharmacist, he received a friendly approach by the local church Capellmeister Mr Glöggl to compose for him so called Equale for 4 trombones for All Souls’ Day (2 November), so that these could be played by his musicians in the customary manner on this feast. – Beethoven showed himself eager to do so; he actually created for this purpose three movements that, though admittedly short, truly bear the master’s touch in the splendidness of the design.

This account tells the story of the ‘original’ Equale, but also immediately poses a number of questions. What exactly is an Equale? What is this ‘customary manner’ of playing at All Souls’ Day? What did the tradition entail and where does it originate? And finally, what can be understood from ‘die Grossartigkeit der Anlage der Meisterhand’ [the splendidness of the design of the master’s touch]?

Beethoven’s pieces are not the only works bearing the title Equale, as it was a name commonly given to pieces written for three or four equal parts (referring to both instrument type and tessitura), usually trombones, which are used to commemorate the dead.[13] A great deal of uncertainty surrounds the exact origin of the musical form called Equale. The above-mentioned Franz Xaver Glöggl, who commissioned Beethoven’s Drei Equale, wrote a guide for music performance during church services (Kirchen-Ordnung) in 1828, in which he mentioned the use of trombones at several occasions.[14] The custom at funerals, according to Glöggl, was to let a group of trombones or other wind instruments play a short mournful piece, an Equale, before the ceremony started, and, alternating with a choir singing the text of the Miserere, during the funeral procession.[15] Othmar Wessely claims that the tradition is local to the area of Linz,[16] and Guion seems to think that the use of the term Equale even originated with Glöggl on that autumn day in 1812 in Linz, which would make Beethoven’s the first Equale ever.[17] There are no other Equale known to be written before that time. However, according to Haslinger, Glöggl asked Beethoven to write the Drei Equale so that they ‘could be played by his musicians in the customary manner on this feast’.[18] This would suggest that the Equale tradition was already established in Linz before Beethoven visited. Another source survives to support that idea: the son of Franz Xaver Glöggl, Franz Glöggl, shortly before his own death, recorded his recollections of Beethoven’s visit to Linz:

Beethoven wünschte aber ein Aequal, wie es in Linz bei den Leichen geblasen wurde, zu hören; so geschah es daß mein Vater an einem Nachmittage 3 Posaunisten bestellte, da Beethoven ohnedies bei uns speiste, und ein solches Aequal blasen ließ, nach welchem sich Beethoven niedersetzte und eines für 6 Posaunen schrieb, welches mein Vater von seinen Posaunisten auch ausführen ließ usw.[19]

Beethoven wanted to hear an Equale as played at funerals in Linz; and one afternoon when Beethoven was expected to dine with us, my father appointed three trombone players and had them play an Equale as desired, after which Beethoven sat down and composed one for 6 trombones, which my father had his trombonists play as well etc.

That Beethoven asked for the specific ‘Linzer Equale’ would certainly support the idea that it was a tradition native to Linz, and that Beethoven’s Equale were not the first to start the tradition.

Another longstanding tradition in Germany and Austria that is relevant in relation to the Equale is that of the Stadtpfeiffer. Many towns had their own group of wind players that would perform at local celebrations and civic ceremonies, as well as in church services and during religious festivals.[20] In some places the players would also be employed as Turmbläser, in which capacity they were required to play from the local church tower at certain feast days,[21] or sometimes even just to sound the hours (Stundenblasen).[22] And even then, the trombones would be associated with divine presence. According to Warren Kirkendale, ‘the Stadtpfeiffer Hornbock in Kuhnau’s Musicalischer Quak-Salber testified: “We know from experience, that when our city pipers in the festive season play a religious song with nothing but trombones from the tower, then we are greatly moved, and imagine that we hear the angels singing”’.[23] An account of the All Saints’ and All Souls’ Day festivities in Linz in 1875 describes a similar manifestation:

Am Festtage aller Heiligen und darauffolgenden Allerseelentag wandeln die Bewohner der Stadt aller Schichten und Stände, jedes Alters und Geschlechtes hinaus auf den Friedhof, um dort die festlich geschmückten Gräber der Verstorbenen zu besuchen oder auch nur der Schaulust und Neugierde zu frönen. Am Abende des Allerheiligen– und am Morgen des Allerseelentages rufen die Stadtmusiker vom Balkone des Rathauses (früher vom Schmidtorturme) mit Posaunen den Lebenden das ernste Memento mori zu.[24]

On the holidays of All Saints’ Day and on the following All Souls’ Day, the inhabitants of the town, all classes and professions, every age group and lineage, walk out to the cemetery to visit the lavishly decorated graves of the deceased, or even just to indulge their curiosity. On the evening of All Saints’ Day and on the morning of All Souls’ Day the Stadtmusiker proclaim with trombones from the balcony of the Town Hall (formerly from the Schmidtorturm[25]) an earnest memento mori for the living.

Could they have been playing Equale there as well? All the other accounts of Equale were in relation to funeral processions, but this could explain why Glöggl commissioned the pieces specifically for All Souls’ Day. With that in mind, it seems likely that Beethoven’s Drei Equale were also first played from the Schmidtorturm (the switch to the Town Hall balcony probably occurred after 1828, when the Schmidtorturm was demolished).[26] Thus far, all the accounts of performances of Equale are describing outside performances, either in funeral processions or from a local tower of some sorts. This would be consistent with the fact that there does not seem to be any account of an Equale actually being played during a service, inside a church.

Interestingly, Franz Glöggl Jr. remembers his father owning a collection of trombones, including a soprano and a quart trombone,[27] but Beethoven chooses not to write for these. Beethoven does not specify which trombones should be used, but he does write the first and second voices in alto clef, the third in tenor clef, and the fourth in bass clef. The attribution of certain clefs to certain parts does not necessarily mean they have to be played on the corresponding instruments;[28] it can simply be a question of comfortable writing in the stave, without the need for many ledger lines. But what is remarkable when looking at Beethoven’s score, is that all four parts are written so close together. If the top parts were played on alto trombones and the bottom part on a bass trombone, the possibilities of their range are not at all fully exploited. In fact, all parts can quite comfortably be played on a tenor trombone. Maybe Beethoven wanted to emphasize the equality of the parts, but it is also possible that he purposely wanted to create a chorale-type sound in which the trombones blend well – a reference to the traditional, vocally inclined trombone parts.

Figure 2 Autograph score of the Equale (Beethoven (1812), as cited in Weiner, ‘Beethoven’s Equali’, 229.)

The choral sublime

One would think that the fact that the Drei Equale were chosen, out of the multitude of pieces suitable for such occasions, to be performed at Beethoven’s own funeral, must surely mean that they were not only considered suitable pieces because of their solemn tone, topical allusions, and the traditions surrounding the Linzer Equale, but also because they were believed to be compositions that represented the composer’s genius. Despite that, recent scholars have not taken kindly to the pieces. Howard Weiner describes them as ‘anything but spectacular masterpieces’,[29] and David Guion even suggests that Beethoven himself would not have cared much for the pieces at all: ‘The “Equali” seem to betray a lack of interest in the trombone, or at least in the commission of the piece. Each one is shorter, less fully developed, and less carefully provided with dynamic markings than the previous one’.[30] The manuscript (Figure 2) indeed shows a sparsely marked score in Beethoven’s hasty handwriting, yet that does not unequivocally prove Beethoven’s disinterest in the Drei Equale. The circumstances surrounding the commission of the pieces did not leave Beethoven with a lot of time to write, which could easily account for both shortness and hastiness. Besides, it was Tobias Haslinger, Beethoven’s publisher and close friend,[31] who recommended the Drei Equale to Seyfried. This may suggest that Beethoven himself never mentioned the Drei Equale in a negative context to his publisher, who otherwise surely would not have considered them appropriate for the funeral. The Drei Equale were not published during Beethoven’s lifetime. The reasons for this are unknown and one can only speculate – one interpretation might be that they were considered of lesser quality. However, other reasons, such as commission history and saleability, could have played a role as well. One can think of good reasons why Beethoven would not be in a hurry to have them published: three short pieces for four trombones (an instrument which had been in a state of decline for more than half a century already, certainly outside of Austria)[32] would most likely not be big sellers. But, again, this is not a comment on the artistic value of the pieces. Haslinger’s short entry in one of Beethoven’s Konversationshefte in 1825/26,[33] ‘Ich werde dann die Equale herausgeben’[34] (I shall then publish the Equale), indicates that Beethoven would have considered them at least representative enough to be published.

Unlike Guion, Trevor Herbert describes Beethoven as being ‘clearly interested in the trombone’,[35] but for a different reason than outlined above. Herbert believes that Beethoven was experimenting with the role of the trombone in the orchestra, and he quotes a writer in The Harmonicon from 1824, reporting that the composer ‘was desirous of ascertaining for a particular composition … the highest possible note on a trombone … but did not seem satisfied [with the answer he was given]’.[36] Herbert continues by claiming that:

the strength of Beethoven’s orchestral scoring for trombones lay in his ability to blend the instruments into orchestral textures. In many ways, this writing is remarkable for its time precisely because the trombones generally signify no programmatic meaning in their own right.[37]

It is true that Beethoven was one of the first composers to use trombones in his non-programmatic orchestral music, paving the way for the next generations of (Romantic) composers and how they treated the trombone in the orchestra, and the revival of the instrument in the course of the nineteenth century.[38] However, it seems unlikely that the symbolism connecting the trombone with death and the divine in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Herbert, too, acknowledges the presence of such a connection in compositions a late as Mozart’s Don Giovanni and the Requiem)[39] would be lost and forgotten just over a decade later. On the contrary, it is likely that Beethoven used these associations, with which the audiences of his time would probably still be familiar, very deliberately to evoke a certain effect.

The Romantic idea of the sublime, or ‘das Erhabene’ in German, leads back to two landmark treatises in the field of aesthetics: Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful of 1757,[40] and Kritik der Urteilskraft (Critique of Judgment) by Immanuel Kant of 1790.[41] They characterize the sublime as the capacity to overwhelm the senses, the contemplation of the infinite, unpredictability, immeasurability, transcendent qualities, fear, pain, awe, and ‘Gottesfurcht’ (fear/respect for God), and they set apart the sublime from the merely beautiful.[42] Towards the end of the century, music began to be acknowledged more and more as one of the fine arts (Kant still considered music to be ‘more enjoyment than culture’),[43] and as such the romantic aesthetic concepts were applied to music as well. In his famous 1810 review of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, E.T.A. Hoffmann wrote:

[instrumental music] is the most romantic of all arts, and we could almost say the only truly romantic one because its only subject is the infinite. Just as Orpheus’ lyre opened the gates of the underworld, music unlocks for mankind an unknown realm – a world with nothing in common with the surrounding outer world of the senses. Here we abandon definite feelings and surrender to an inexpressible longing.[44]

It was especially the absolute, instrumental music that was viewed as the perfect vehicle for the sublime and the transcendent, for it does not aim to imitate or describe it (as poetry and visual art do), but rather has the capacity, with its exclusively musical power, to embody it completely and create an entirely new realm.[45] The eighteenth-century German composer Johann Abraham Peter Schulz described the symphony as ‘especially suited to the expression of the grand, the solemn, and the sublime’.[46] Hoffmann names Beethoven’s greatest predecessors of the symphonic genre, Haydn and Mozart, as the foundation of Beethoven’s sublime style.[47]

However, as Nicholas Mathew clearly lays out in his book Political Beethoven, the sublime style found in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century orchestral canon is not a symphonic-instrumental concept to begin with, but rather one that is deeply rooted in the great choral tradition of the first half of the eighteenth century.[48] Mathew quotes Carl Dahlhaus, saying that ‘Beethoven found his models for the sublime style in Händel’s oratorio’s, rather than in earlier instrumental music’,[49] before reminding us of the ‘sublime hymns’ that conclude the Fifth, Sixth, and, most obviously, the Ninth Symphonies.[50] Incidentally, these are also the only symphonies in which Beethoven chose to write parts for trombones. Mathew makes the comparison between the beginning of the fourth movement of the Fifth Symphony, ‘Beethoven’s best-known transition from metaphorical darkness to light’,[51] and the moment in Haydn’s oratorio Die Schöpfung (1798) when the creation of light itself is represented by ‘dazzling brass and timpani and sudden switch from C minor to C major’.[52] It is exactly that moment, at the transition of the third to the fourth movement of the Fifth Symphony, with the sudden change from C minor to C major and the entrance of a majestically liberating hymn, that marks the first ever trombone entrance in any of Beethoven’s symphonies.

Beethoven’s specific use of the trombone at such distinct moments suggests that he was making a very deliberate choice. The trombone, with its history of being used for communicating the power of the divine and the afterlife, or, in other words, the transcendent and the infinite, may even be regarded as the ultimate incarnation of the divine into the secular symphony: the choral sublime. This would explain why the trombone parts in Beethoven’s symphonies are so sparingly written, always in a chorale style, never virtuosic,[53] and often independent from other instrumental groups. Nonetheless, all these attributes are explained by Guion as either stemming from a lack of accomplished trombone players at the time, or from a general disinterest for the trombone on Beethoven’s side. Guion concludes that ‘for whatever reason, Beethoven exploited only the least interesting of the trombone’s capabilities’.[54] If Beethoven indeed used the trombone to communicate a sense of ‘Gottesfurcht’ at the highpoints of sublimity in his symphonies, it is much more likely that he wrote the parts in a (relatively simple) chorale style to make a connection to the trombone’s topoi of the past. In this light, using a trombone quartet at the funeral of the great genius suddenly seems very fitting.

Master of time

The simplicity of the Drei Equale may account for the lack of critical engagement by scholars. However, an analytical reading of the pieces will strengthen the idea of a conscious simplicity in Beethoven’s writing, and will also show that this apparent simplicity is underpinned by an ingenious musical structure. The three short movements constituting the Drei Equale are perfect examples of Beethoven’s dependence on the basic elements of tonal structure, providing both overarching form and broadly thematic material, while the melodic material is quite minimal and rather unremarkable. All three of the movements share a rhythmic motive of a dotted minim followed by a crotchet, and another motive of two upbeat crotchets in the first and second Equale and a very similar figure of three upbeat crotchets in the third. Unlike the Classical composers that came before him, Beethoven does not usually build his structure around regular, complete melodic themes, but rather around small melodic, or in this case mainly rhythmic, motives.[55] As a result of this, the harmony and the structure are carrying more of the expressive weight.

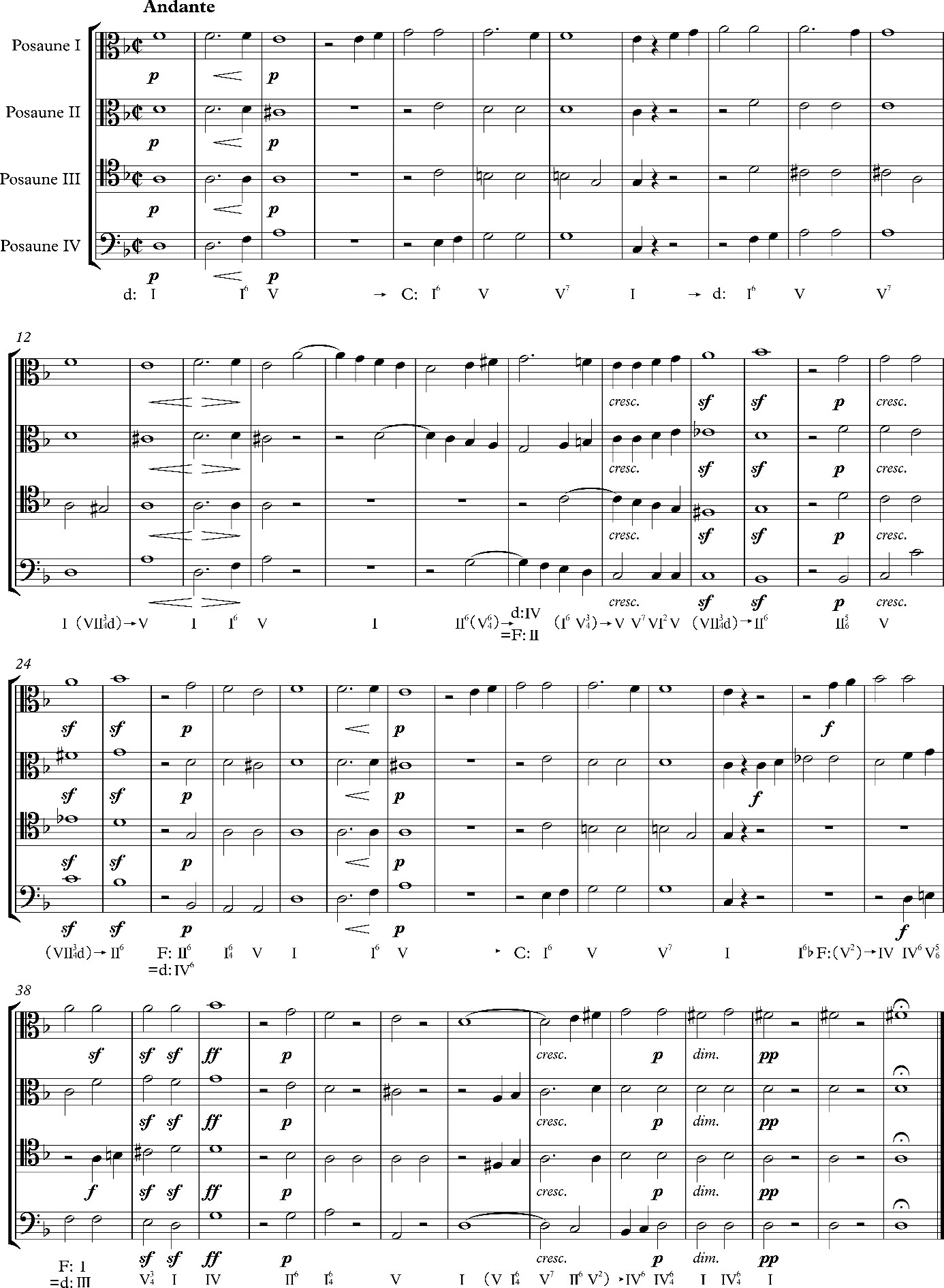

Although the Drei Equale are at first glance written within the established late eighteenth-century harmonic idiom, they are marked by a distinctive evasion of a strict dominant–tonic relation (a general characteristic of Beethoven’s style and one of the reasons he is so often labelled as straddling the Classical and Romantic styles).[56] With the absence of certain anticipated cadences and modulations (‘vertical’ points of recognition), the listener is thrown off guard, and an overarching sense of timelessness is created. In the first movement for instance (Figure 3), Beethoven chooses never to modulate to the dominant key throughout the entire piece, which could be interpreted as an attempt to play with the listener’s sense of anticipation within an apparent rounded binary form. Another noteworthy detail is the total absence of perfect authentic cadences, which similarly suggests that Beethoven is deliberately circumventing the feeling of finality and consequently tampering with the perception of time, a quality that permeates the entire piece.

Upon hearing the opening statement of the first Equale, one is immediately thrown off guard by the lack of confirmation of the main key of D minor. The first three bars sound almost like a plagal cadence in A, as if the composition begins in the middle, without a clear beginning. The ambiguous opening gesture is reiterated twice again later in the piece, in bars 14–15, and in bars 27–29. The first ‘echo’ is placed at the end of the first main phrase, added as an afterthought, which contributes to the idea that these bars are not an actual opening statement. Here, the motive is also part of a somewhat masked pedal point that runs through bars 10–15, as the harmonic progression comes to a halt for six full bars (a relatively long time in a piece counting only 50 bars); the tonic chords on bars 12 and 14 distinctly do not feel like a ‘coming home’, and the A runs between the parts at all times (except for the second half of bar 12 which, incidentally, is the only time in the piece when the leading tone to the dominant, G#, is heard). Although this might not be a fully formed pedal point, there is certainly a typical sensation of interrupted motion.

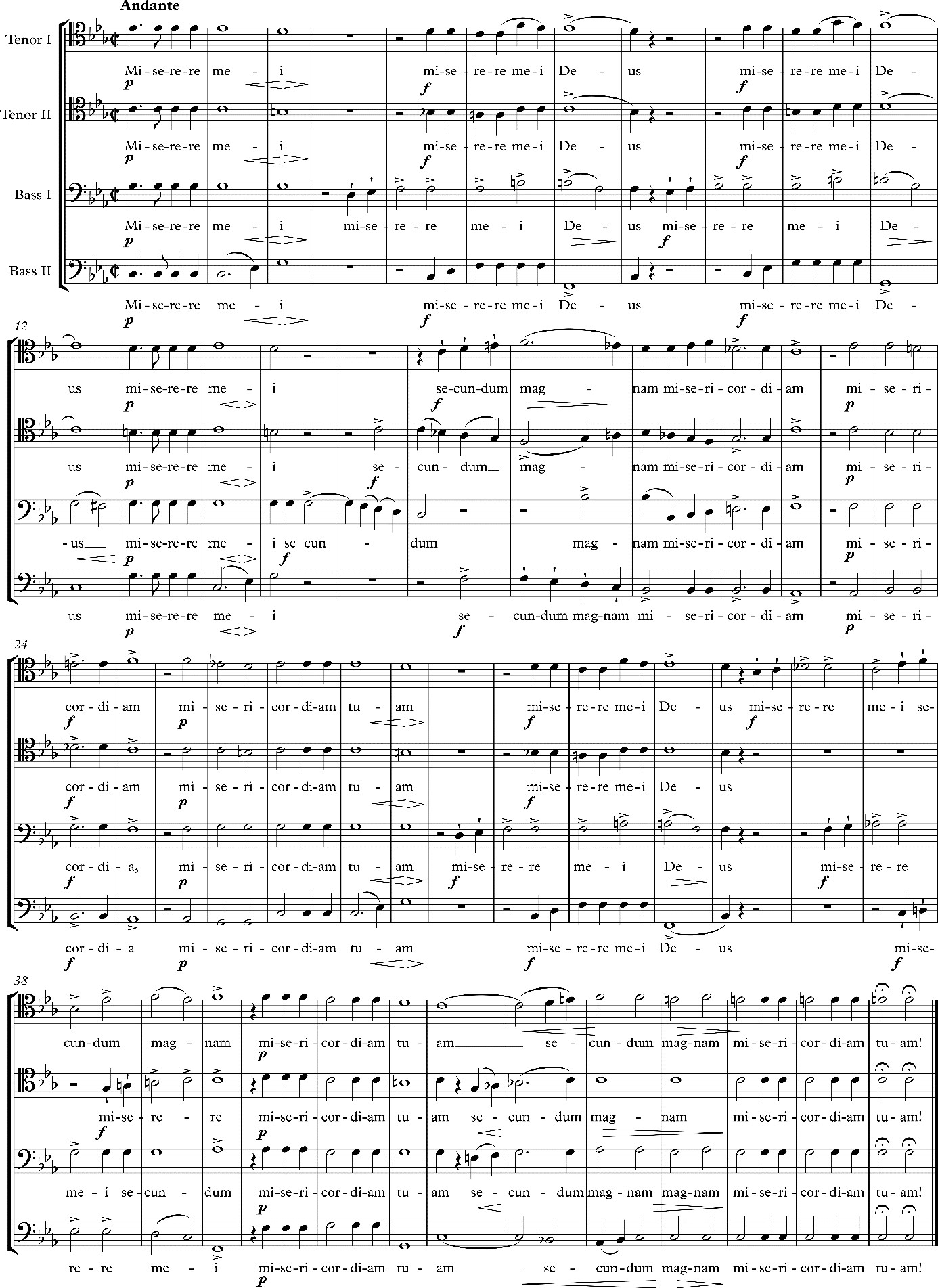

An imitative descending line then leads the way to the relative key of F major, which is never confirmed by a cadence, but instead leads to the first climactic moment of the piece, as the dominant C major chord on the last beat of bar 19 does not resolve to F major, but is followed instead by a sf diminished F# seventh chord and a sf G minor chord. This chord progression is repeated, only this time the two sf chords are in a closer voicing to increase the feeling of suspension, exactly at the halfway point of the piece. With the simplest means possible Beethoven then presents the reprise: just three minims of release after such a drawn-out build-up of tension. By cleverly playing with the composition’s structural proportions in this manner, the reprise, and thus the second echo of the opening statement, is made to be experienced as emerging prematurely out of the climactic outbursts preceding it. A recollection of the pedal point that accompanied the first echo of the opening statement, manifests itself in the repeated A in the third trombone part (bars 27–30), and yet again Beethoven manages to create an effect of timelessness, as if plunging right into the middle of the music instead of starting at the beginning. Seyfried also seems to recognize this when he set the Miserere text to this first Equale (Figure 4): the reprise remarkably starts in the middle of a word (on the syllable ‘-cor’ of ‘misericordiam’).

The first seven bars of the reprise are identical to the beginning, but instead of continuing the sequence in the same way as in bar 8, a comparable entrance in the second trombone part leads to a hard change from C major to C minor in bar 36 instead. A change that is (inversely) reminiscent of the sudden C major start of the fourth movement of the Fifth Symphony. Instead of a symbol of liberation, this modal change could be perceived as the ‘Gottesfurcht’ that accompanies the inevitability of death. The same melodic ascending motive is then repeated in the other three parts, of which the entrance notes follow the circle of fifths, just like the entrances in bars 15–18. When the G minor climax is reached again in bar 40, it is now marked ff to ensure its tension is maintained for the entire chord, after which a full ten bars is used to release the tension, in which Beethoven writes two more pedal points, in bars 42–43, and 46–47. This time, however, they are totally exposed, as they lead the way to the ending statement of three repeated pp D major chords, which could be construed as an affirmative, if humble Hallelujah.[57]

Figure 4 Transcription of Seyfried´s version of the first Equale, with added text and different dynamic and expressive markings. (Seyfried, Trauer-Gesang bey Beethoven’s Leichenbegängnisse.)

This example shows how the careful manipulation of the perception of time and the conscientiousness of the musical structure can carry the expression that is seemingly lacking from the melodic material. When Rosen writes that ‘structure replaced ornamentation as the principle vehicle of expression’ and ‘proportions are an essential part of meaning’,[58] he is usefully describing the phenomenon that is so clearly audible in the Equale. Furthermore, it is exactly the technical simplicity of the trombone parts and the minimalistic melodic material that critics have mistaken for disinterest or even ignorance, which uncovers the meticulously composed structures and proportions in their glorious nakedness. Could this be the ‘splendidness of the design of the master’s touch’ of which Seyfried was speaking?

Resembling the voice

Early nineteenth-century trombone players would have been very accustomed to playing together with singers, since most of the repertoire still only asked for trombones in choral settings. Therefore, the way of playing would have been mild and well suited for blending with voices. In 1811 Joseph Fröhlich published his Vollständige theoretisch-praktische Musikschule, in which he dedicates a chapter to the trombone. When writing about the style and sound of the instruments he states that ‘Der Posaunist muss sich daher ganz nach der Singschule bilden, und ein gutter Sänger kann dessen einziges Muster seyn’ (The trombonist must therefore model himself entirely according to vocal teaching, and a good singer can be his proper example).[59] Fröhlich continues:

Der Character des Instrumentes, besonders geeignet zum Ausdruck des Erhabnen, Feyerlichen, welchem auf der andern Seite das Sanfte Ruhige entspricht, sowie die gewöhnliche Bestimmung desselben, jene der Begleitung von Singstimmen erfordert es, dass der Vortrag auf demselben gehalten, gesangvoll, und ja nicht zu grell sein dörfe, um so die möglichste Annäherung an diejenige Stimme zu bewirken, welche jede dieser Posaunen im Satze begleitet, oder vorstellt [ … ] Soviele Wirkung eine schöne Harmonienfolge auf diesen Instrumenten mit Seele und einem verhältnissmässig modificirten Ansatze vorgetragen immer hat, und haben muss, so wiederlich, und allen guten Eindruch verderbend ist es, wenn Posaunen mit einem wilden schmetternden Tone geblasen werden wenn es nicht ausdrücklich von dem Tonsetzer angezeigt ist.[60]

The character of the instrument is best suited for the expression of the sublime and solemn, which suits the gentle and calm, as well as its usual role of doubling voices. Its character requires that its execution be kept melodious and not too shrill, in order to bring out the closest resemblance to the voice that each trombone doubles or represents … Just as a beautiful result of harmonies always has, and must have, so much effect on this instrument when it is played with soul and gentle articulation, so it is revolting and spoils all good impressions when the trombone is played with a wild and blaring tone, if the composer has not expressly indicated it.

Remarkably, Fröhlich uses the term ‘sublime’ to express the character of the trombone here. The warm, vocal sound of the trombone quartet, with all its historical allusions, could be interpreted as the ultimate instrumental personification of the choral sublime.

Singing angels

The Drei Equale might have come down to us as merely insignificant occasional pieces, but instead they were chosen to be performed at Beethoven’s funeral, and were thus saved from obscurity. Critics and scholars have characterized the Drei Equale as simple, uninspired pieces. To a nineteenth-century audience, however, they would have evoked immediate allusions that change that perception drastically. The history of the trombone as an instrument associated with the voice of God and imageries of the afterlife made the trombone quartet an eminently suitable choice for a funeral. Assuming that this connection was well known to Beethoven himself, it would also have greatly influenced the way he composed them 15 years earlier.

Luck would have it that Beethoven visited his brother in Linz shortly before All Souls’ Day, and that Capellmeister Glöggl was astute enough to convince him to write the pieces. It must have been an impressive moment when the newly composed Equale were first sounded from the top of the Schmidtorturm, reaching the ears of all the inhabitants of Linz who were commemorating their deceased loved ones. Beethoven would have written the pieces deliberately in a solemn tone, in ‘equal’ parts, resembling a chorale. The technically unchallenging trombone parts resemble Beethoven’s orchestral writing for the instrument. But instead of dismissing this as the result of mere disinterest or mediocrity, it could be interpreted as a celebration of the choral sublime and a conscious tribute to history and tradition. The trombone chorale was meant to inspire a sense of infinity and transcendence; no fanfare and virtuosity was needed or expected. The analysis in this article has shown how Beethoven’s deliberate choice to compose simple trombone parts led to the uncovering of the structures and proportions of the piece – this is where their true expressive quality lies. It also showed how Beethoven ingeniously manipulated the perception of time and that, too, evokes a sense of the sublime.

This is what the people of Linz will have heard, just like the tens of thousands of people gathering for Beethoven’s funeral 15 years later. It sheds a new light on the Drei Equale and on Beethoven’s treatment of the trombone in general, and it finally truly explains Stadtpfeiffer Hornbock’s reference to trombone playing as the sound of singing angels: the ultimate, awe-inspiring union of the choral sublime and the divine.

Endnotes

[1] Jan Caeyers, Beethoven, een biografie (Amsterdam: De Bezige Bij, 2019), 15.

[2] Christopher Gibbs, The Life of Schubert (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 139.

[3] See Ignaz Ritter von Seyfried, Trauer-Gesang bey Beethoven’s Leichenbegängnisse, in Wien den 29. März 1827 (Vienna: Tobias Haslinger, 1827). See Scott Burnham and Michael Steinberg, Beethoven and his world (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000) 246. The remaining movement of the Drei Equale was adapted for Beethoven’s memorial service a year later, using a poem by Franz Grillparzer. The arranger of the second Equale is not mentioned anywhere, but as it is published by Seyfried along with the other two movements, it is most likely that he arranged this movement as well. See Ignaz Ritter von Seyfried, Ludwig van Beethoven’s Studien im Generalbasse, Contrapunkte und in der Compositions-Lehre (1832) (Leipzig: Schuberth, 1853).

[4] Seyfried, Trauer-Gesang bey Beethoven’s Leichenbegängnisse. Although the Seyfried’s note – Welche nun auch bey Tob. Haslinger erschienen sind – suggests that the Equale were also published in their original form at the same time, there is no evidence to support this. The earliest known ‘original’ edition is part of the Beethoven Complete Edition in 1888, as published by Voss in 2012 (Egon Voss, ‘Preface’, to Ludwig van Beethoven, Drei Equale, für vier Posaunen, WoO 30 (München: G. Henle, 2012)). It is unclear whether the pieces were meant to be performed by singers and trombone players at the same time, or in alternation. In Haslinger’s publication no score is included, only separate parts, but the title page reads ‘mit willkührlicher Begleitung von vier Posaunen, oder des Pianoforte’ (arbitrarily accompanied by four trombones, or piano), and a piano score is included in the edition, implying that they would have been played at the same time. See Seyfried, Trauer-Gesang bey Beethoven’s Leichenbegängnisse, title page. However, the introduction states that the male choir was playing alternately with the trombone quartet (‘alternirend mit dem Trombonen-Quartett); see ibid, 1.)

[5] Stewart Carter, ‘Review of Charlotte Leonard, ed., Seventeenth-Century Lutheran Church Music with Trombones’, Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music, 11/1 (2005), https://sscm-jscm.org/v11/no1/carter.html#ch4.

[6] Trevor Herbert, The Trombone (London: Yale University Press, 2006), chapter 5.

[7] Herbert, The Trombone, 101.

[8] Herbert, The Trombone, 101.

[9] Stewart Carter, ‘Trombone obligatos in Viennese oratorios of the Baroque’, Historic Brass Society Journal, 2 (1990), 52–77, here 52.

[10] Schubart, as cited in David Guion, The Trombone, Its History and Music, 1697–1811 (New York: Gordon and Breach, 1988), 86.

[11] Christopher Reynolds, Motives for Allusion: Context and Content in Nineteenth-Century Music (London: Harvard University Press, 2003), 9.

[12] Seyfried, Trauer-Gesang bey Beethoven’s Leichenbegängnisse, 1.

[13] Maurice Brown, ‘Equale’, Grove Music Online. Accessed 8 March 2018.

[14] Franz Glöggl, Kirchenmusik-Ordnung, erklärendes Handbuch des musikalischen Gottesdienstes, für Kapellmeister, Regenschori, Sänger und Tonkünstler (Vienna: Wiener Stadtbibliothek, 1828).

[15] Glöggl, Kirchenmusik-Ordnung, 20–21.

[16] Wessely, as cited in Eileen Watabe, Chorale Topic from Haydn to Brahms: Chorale in Secular Contexts of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries (PhD diss., University of Northern Colorado, 2015), 34.

[17] David Guion, A History of the Trombone (Lanham: Scarecrow, 2010), 149.

[18] Seyfried, Trauer-Gesang bey Beethoven’s Leichenbegängnisse, 1.

[19] Glöggl, as cited in Alexander Wheelock Thayer, Ludwig van Beethoven (Große Komponisten) (Altenmünster: Jazzybee Verlag, 2012), 351. The younger Franz Glöggl wrote about a piece for six trombones, while all three Equale known today are written for four parts. It is possible that Beethoven wrote a fourth Equale in six parts, which should then be considered lost. Another explanation could be that Franz Glöggl remembered it incorrectly; after all, the event had happened almost 60 years earlier. If there would have been a fourth Equale, though, it could have been written on the leaf that was torn off the double folio leaf on which the third Equale was originally written. But then again it could also just be an empty piece of paper that was torn off. See Howard Weiner, ‘Beethoven’s Equali (WoO 30): A New Perspective’, Historic Brass Society Journal, 14 (2002), 215–77, 233.

[20] Trevor Herbert, The Trombone (London: Yale University Press, 2006), 70.

[21] Gerlinde Haid, Turmblasen. Österreichisches Musiklexikon, online edition (2002),www.musiklexikon.ac.at/ml/musik_T/Turmblasen.xml. Accessed 8 March 2018.

[22] Axel Fischer, Das Wissenschaftliche der Kunst: Johann Nikolaus Forkel als Akademischer Musikdirektor in Göttingen (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2015), 45.

[23] Warren Kirkendale, ‘New Roads to Old Ideas in Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis’, in Beethoven, ed. Michael Spitzer (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015), 134.

[24] Fink, as cited in Weiner, ‘Beethoven’s Equali’, 228.

[25] The Schmidtorturm, or Blacksmith Gate Tower, was a tower overlooking the main square in Linz.

[26] Otto Constantini, Das barocke Linz (Linz: Feichtinger, 1966), 15.

[27] Glöggl, as cited in Voss, ‘Preface’, IV. According to Voss the quart trombone was probably a trombone in F, a contrabass trombone avant la lettre.

[28] The use of alto clef for certain trombone parts has fuelled a longstanding debate about when the alto trombone should actually be used. In the trombone concertos by Johann Georg Albrechtsberger (1769) and Georg Christoph Wagenseil (1755–1759), for instance, which are both written in alto clef, the prescribed trills become rather unidiomatic on the alto trombone, which is why they are also regularly played on tenor trombone.

[29] Weiner, ‘Beethoven’s Equali’, 215.

[30] Guion, The Trombone, Its History and Music, 136.

[31] Peter Clive, Beethoven and His World: A Biographical Dictionary (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 152.

[32] Herbert, The Trombone, chapter 6.

[33] During the last decade of his life, when his deafness had become a seriously limiting factor, Beethoven started carrying a blank ‘conversation booklet’ with him at all times. His acquaintances wrote their side of the conversation down, while he answered aloud. He also often used these books as notebooks to scribble down anything from shopping lists to sketches for new compositions.

[34] Ludwig van Beethoven, Konversationshefte, Band 8, Hefte 91–103, ed. Karl-Heinz Köhler and Grita Herre (Leipzig: Deustscher Verlag für Musik, 1981), 79.

[35] Herbert, The Trombone, 175.

[36] Herbert, The Trombone, 175.

[37] Herbert, The Trombone, 175.

[38] An excellent discussion of this topic can be found in chapter 8 of Herbert, The Trombone, 151–81.

[39] Herbert, The Trombone, 118.

[40] Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757) (Mineola: Dover Publications, 2008).

[41] Immanuel Kant, Kritik der Urteilskraft (1790) (Hamburg: tredition GmbH, 2012).

[42] For a detailed discussion of the sublime as a Romantic aesthetic concept, see Robert Doran, The Theory of the Sublime, From Longinus to Kant (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

[43] Kant, as cited in Albert van der Schoot, ‘Musical sublimity and infinite Sehnsucht – E.T.A. Hoffmann on the way from Kant to Schopenhauer’, Proceedings of the European Society for Aesthetics, 6 (2014), 344–54, here 345.

[44] Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann, ‘Review of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony’ (1810), in E.T.A. Hoffmann’s Musical Writings: Kreisleriana; The Poet and the Composer; Music Criticism, ed. David Charlton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 96.

[45] Lydia Goehr, The Imaginary Museum of Musical Works: An Essay in the Philosophy of Music (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994), 155.

[46] Schulz, as cited in Mark Evan Bonds, Music as Thought (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006), 46.

[47] Hoffmann, ‘Review of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony’, 96.

[48] Nicholas Mathew, Political Beethoven (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 126.

[49] Dahlhaus, as cited in Mathew, Political Beethoven, 126.

[50] Mathew, Political Beethoven, 129–30.

[51] Mathew, Political Beethoven, 107.

[52] Mathew, Political Beethoven, 1.

[53] Beethoven most likely would have been familiar with more virtuosic trombone writing, as he would probably have been familiar with the virtuosic obligato writing in Viennese oratorio and with the trombone concertos that were written in the eighteenth century, amongst which there is also one by Beethoven’s old composition teacher Johann Georg Albrechtsberger.

[54] Guion, The Trombone, Its History and Music, 283.

[55] Charles Rosen, The Classical Style, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven (London: Faber and Faber, 2005), 394.

[56] Maynard Solomon, Late Beethoven: Music, Thought, Imagination (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 7.

[57] D major is the key associated with joy and Hallelujah, as put forth by Christian Schubart in his Ideen zu einer Aesthetik der Tonkunst, written in 1806 (Christian Schubart, C.F.D. Schubart’s des Patrioten gesammelte Schriften und Schicksale (Stuttgart: J. Scheible’s Buchhandlung, 1840), pp 381–4.), and repeated by Glöggl in his Kirchen-Ordnung in 1828; see Franz Glöggl, Kirchenmusik-Ordnung, erklärendes Handbuch des musikalischen Gottesdienstes, für Kapellmeister, Regenschori, Sänger und Tonkünstler (Vienna: Wiener Stadtbibliothek, 1828), 8–9. In the Drei Equale Beethoven chooses not to use any of the keys directly associated with death or mourning (A flat minor and F minor), but rather those linked to melancholy (D minor), Hallelujah (D major) and hope (B flat major), instead.

[58] Rosen, The Classical Style, 395.

[59] Joseph Fröhlich, Vollständige theoretisch-pracktische Musikschule (Bonn: Simrock, 1811), §3 29.

[60] Fröhlich, Vollständige theoretisch-pracktische Musikschule, §3 27.