Exploring the Embodied Music Practice of the West African Balafon Culture:

The Challenges and Potential to a Western Classical Marimba Performer

Table of contents

DOI: 10.32063/0205

Adilia Yip

Adilia Yip is a marimba performer and works at the Royal Conservatory of Antwerp as artist researcher. At the same time, she is doctoral candidate in musical arts at the Orpheus Institute, Ghent, Belgium. Her main research interest is the embodied performance practice of the marimba and the instrument’s origin— the West African balafon.

by Adilia Yip

Music + Practice, Volume 2

Explorative

- Introduction

- Field studies

- The instrument and the playing technique

- Communicating the rhythm

- Understanding the body coordination in rhythm

- Confusion in learning the ‘rhythm’

- Communicating the melodic materials

- Embodied movement as a vehicle of communication

- Musical notation vs. oral transmission

- Conclusions: Reflections on artistic improvements

- Footnotes

Introduction

With immense energy and technical dexterity, the hardly explicable musical experience of the West African balafon culture has drawn my attention to the ethnic origins of my practice. In this article, I describe the findings of my field study of West African balafon music, a study based on the method of participant-observation. As a Western art music performer of marimba and percussion, my artistic views were significantly influenced by my encounter with this oral performance tradition. In particular, I will discuss the issues of ‘rhythm’ and embodied practice, and further try to explain certain characteristics of this balafon culture, aided by both my practical approach and relevant literature.

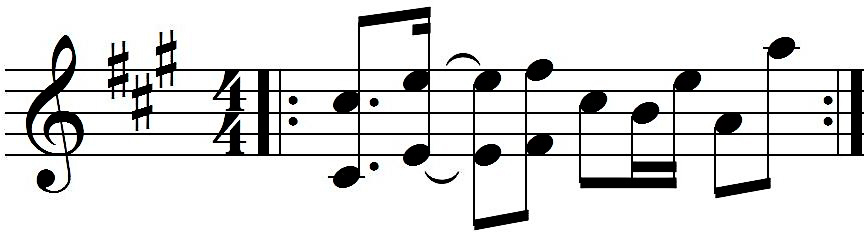

Distinguished by its oral tradition, the balafon performance practice is communicated and passed on without the aid of any form of notation. Music is considered holistically, i.e. in its entirety, and the basic learning method is by listening and imitation. Already during the very first balafon workshop I attended, given by European musician Gert Kilian, I was alerted to the obstacles of learning via oral transmission when used to music reading only. To my surprise, it took almost one afternoon to grasp the full idea of song Sanata, which contains two simple balafon patterns in 4/4 time for four measures and the melody of the song played in single notes or octave doubling (see Figure 1). Obviously, I had difficulties to adapt physically to the technical difference between the balafon and the marimba; the marimba is a double row, well-tempered 12-tone keyboard, whereas the balafon is a pentatonic single row keyboard. 1)The balafon I played during this field study is built by Youssouf Keita, tuned in pentatonic scale according to the Western temperament. Nevertheless, the main challenge was caused by the balafon practice itself. For instance, the subjects typically taught in music conservatories, like the solfège system and score reading/music theory, do not provide all necessary skills to learning the balafon repertoire the traditional way. Why was my classical music training insufficient?

My active participation in learning to play the balafon was an important part of my method: participant-observation. 2)Participant-observation is a process enabling researchers to learn about the activities of the people under study in the natural setting through observing and participating in those activities. See Barbara Kawulich, ‘Participant Observation as a Data Collection Method’, in Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6/2 (2005), art. 43. It is believed to be one important research technique in ethnomusicology and related research subjects. John Baily emphasizes the importance of learning the Herati dutār and the Afghan rubāb is that it allowed him to understand the music from the ‘inside’. John Baily, ‘Learning to Perform as a Research Technique in Ethnomusicology’, in British Journal of Ethnomusicology, 10/2 (2001), pp. 85–98. John Blacking gathered valuable data through learning how to sing the Venda children songs with local teachers, as he could learn from mistakes immediately and began to learn what was expected of a singer and what was tolerated. See John Blacking, Venda Children’s Songs (Johnannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1967). Through interviews, participation in workshops, private lessons and rehearsals with balafon musicians, I was able to observe the balafon performance practice and the teaching methods from the ‘inside’. The angle of a performer is helpful when it comes to contextualizing a music culture that stands vividly in front of my eyes but is seldom analyzed. 3)In the vast literature on African music, there are few discussions of the performance practice of pentatonic balafon; Gert Kilian and Eric Charry have described the instrument, the musical theory and the music culture, but they did not examine the embodied performance experience of the balafon musicians. See Gert Kilian, The Balafon with Aly Keita and Gert Kilian (DVD + booklet, Improductions, 2009) and Eric Charry, Mande Music (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000). Gerard Kubik discusses the perception of patterns and movement in relation to the recognition of rhythmic and melodic materials in African music, which he called ‘inherent patterns’. See Gerard Kubik, ‘Pattern Perception and Recognition in African Music’, in The Performing Arts: Music and Dance, vol. 10, ed. John Blacking and Joann Kealiinohomoku (The Hague: Mouton, 1979).

Field studies

I undertook my first field trip in January 2012 to Konsankuy, Mali, a village of the Bobo tribe, and the second one, in 2013, to Bobo Dioulasso, the second biggest city of Burkina Faso. I took lessons with four African balafon musicians who all practice a similar balafon tradition of the Bobo and Bamana tribes: Youssouf Keita, Kassoum Keita, Moussa Dembele and Mandela. 4)Moussa Dembele is a multi-talent musician; he plays balafon as his main instrument as well as kora and djembe. He is a cousin of the Keita brothers. He lived in the city Bobo Dioulasso in Burkina Faso in the same neighbourhood as the Youssouf Keita’s atelier, a reason why they often play concerts together. Moussa Dembele is now living in Belgium. Mandela (Oumarou Bambara) is a balafon musician from Bobo Dioulasso who now resides in Paris. I had some lessons with him during the second field trip, and he is an acquaintance of the Keita brothers. I further attended workshops with the European balafon musician Gert Kilian in France and Seydouba ‘Dos’ Camara from Guinea.

The daily routine of the workshops with Youssouf and Kassoum Keita were roughly divided into three sessions: a demonstration of the music in the morning, individual practice in the afternoon and, toward the end of the day, the teachers played the song again – the main theme and the patterns – for the participants to videotape. Some extemporaneous performances of the teachers have provided valuable information. Towards the end of the period, a concert was organized by the teachers and the students in collaboration with musicians from the neighbourhood.

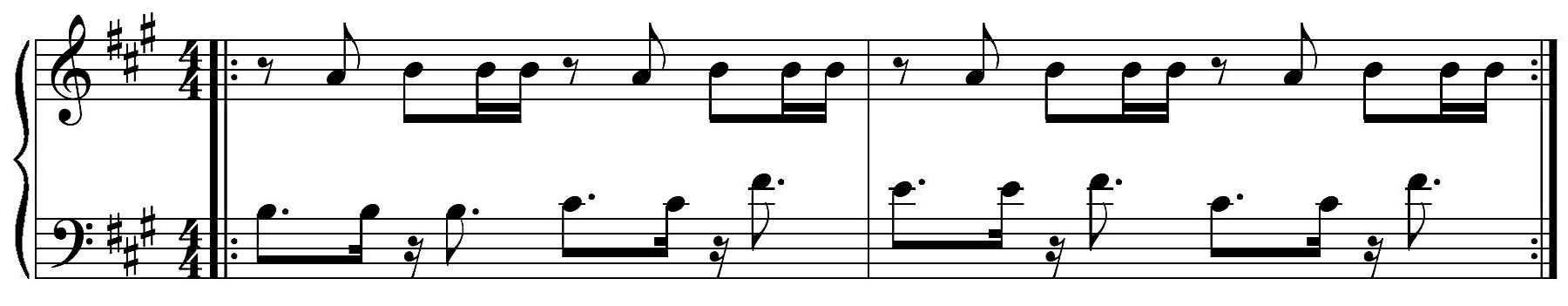

Youssouf always started the day with the story of the song. These songs have a variety of themes: to educate the people, for festivity, to cheer up workers in the fields, etc. After the story, Youssouf demonstrated the song on balafon. He usually began with the melodic theme and the patterns. The melodic theme is the centre of the song, played in octave doubling, and the patterns are composed of elements extracted from the main melody but polyrhythmic in nature. According to their personal preferences and the knowledge passed down from their father, their first balafon teacher, the Keita brothers define the patterns into short structures, i.e. patterns A, B, C and shuffle, instead of explaining these as lengthy music phrases, as some other balafon musicians do. The patterns and melody are played superimposed or Connected consecutively. Technically speaking, a pattern is made up of two linear melodic fragments played by the left and right hand, using one mallet in each hand. It requires a high level of independent arm coordination. Figures 2a and 2b show the main melody and the patterns of Boro Demborola, transcribed by Gert Kilian.

Figure 2a Western notation of Boro Demborola: pattern A (above) and pattern B (below), transcribed in Kilian, The Balafon, booklet.

The instrument and the playing technique

There are different types of balafon in West Africa, varying in construction and tuning according to the geographic origins of the musician and the builder. Usually, the same tuning system is observed within a single village or family. 5)Kilian, The Balafon, Charry, Mande Music, p. 13. Julie Strand, The Sambla Xylophone: Tradition and Identity in Burkina Faso (PhD Dissertation, Wesleyan University, 2009), p. 256, has listed the gourd-resonated xylophones found in Burkina Faso according to the ethnic groups. For the Bobo and Bamana tribes, a single-row pentatonic balafon is one of the main musical instruments used in rituals and daily activities. The same type of balafon is used in our workshops and rehearsals, which is built by Youssouf Keita, the builder of the Keita brand. It usually consists of 20 wooden slats made from rosewood and different sizes of natural calabashes as resonators. After the calabashes are dried and emptied, one to three small holes are cut on the shell with a centimetre in diameter. These holes are covered by fine membranes to produce buzzing effect.

Youssouf usually tunes his instrument in a pentatonic scale on A (A–B–C#–E–F#) in Western temperament, resulting in four pentatonic registers. The range and tuning can be tailor-made upon request; for example, Youssouf has made new balafons tuned in a pentatonic C# scale for a student. When Youssouf is tuning the wooden slats, an electronic tuner is used to help fine-tune the correct frequencies of the Western temperament of equal tuning. It is no surprise that he endorses a tempered tuning due to the Western influence; but it is a pity that we can no longer hear the tuning used by the Keita family before Western influence. Also, Youssouf has designed a new product, the ‘marim-balafon’ or ‘bala-rimba’, a double-row balafon that is tuned to a chromatic scale, similar to the black and white keys of a piano. These acts show us how the Keita family defines the tradition of their instrument: they are little concerned about preserving the original construction and tuning, as a tempered tuning provides more opportunities to collaborate with Western musicians and can result better instrument sales and promoting their music to the Western audience.

Sound is produced by striking the wooden slats with rubber mallets. The rubber mallet is densely wrapped by latex, mounted on a thick wooden stick with a diameter of three centimetres. The contact with the wooden slat is rather supple due to the latex band, which can produce a cushioned impact and a round sound. The two sticks are not necessarily balanced in weight and size. Usually, the left hand takes a slightly softer and bigger mallet, and thus, heavier than that for the right hand. Such mallet is better for sounding the lower notes, so the relatively harder mallet in the right hand can sound clear in the high registers.

In most cases, balafon musicians hold one mallet in each hand and a maximum of two when they want to add more tone colours; in the latter case, usually the upper or lower interval one wooden slat apart is added. There are two ways to hold the sticks: between thumb and forefinger, or between the forefinger and middle finger. Both ways are acceptable to all balafon musicians I have met so far.

Communicating the rhythm

In Western vocabulary, we would not hesitate to use the word ‘rhythm’ to explain temporal occurrences in African music of different regions. But interestingly, the word seems to be absent from African languages. 6)Kofi Agawu, Representing African Music– Postcolonial Notes, Queries, Positions (New York: Routledge, 2003), pp. 62–3 and 151–71. Further, Arthur M. Jones in Studies in African Music (London: Oxford University Press, 1959) wrote extensively on African rhythm in Ewe music, but reported that hardly any term in the Ewe language is found cognate to rhythm in English. Eric Charry vaguely defines rhythmic events of the Mande balafon music as ‘the flow of events over time’, trying to clarify the absence of precise vocabulary of rhythm in the verbal language of the Mande People. 7)Charry, Mande Music, p. xxvii and p. 210, claims that he has not come across an extensive vocabulary related to rhythm. The Mande people are a large family of the ethnic group of West Africa who speak the Mande languages of the region. Mande groups include the Soninke, Bambara (Bamana), and Dyula.

Instead of using the term rhythm, Youssouf has his own ways to explain the time matter. At first, he played the patterns on the balafon without any references as in Western music – metre, tempo, pulse or any other system that can help us to define the time lapse between each note or the groove of a phrase – and ask us to imitate. In fact, he illustrates the musical time events by showing the coordination of the hands. Hand coordination becomes a parameter to demonstrate the time lapse. As the balafon patterns are composed of two superimposed melodic lines (each line played by one mallet), each melodic line, controlled by one hand, forms a referential common beat to the other. ‘Rhythmic feeling’ is harder to comprehend in a single line melody due to the weak reference to the metrical sense or the rhythmic groove in the teaching. These videos of the song Barica can show the complex rhythmic patterns. Video 1 presents the melody and patterns of the song; Video 2 is the complete version of combining the melody and patterns.

Video 1 The melody and patterns of song Barica.

Video 2 The complete performance of Barica.

Understanding the body coordination in rhythm

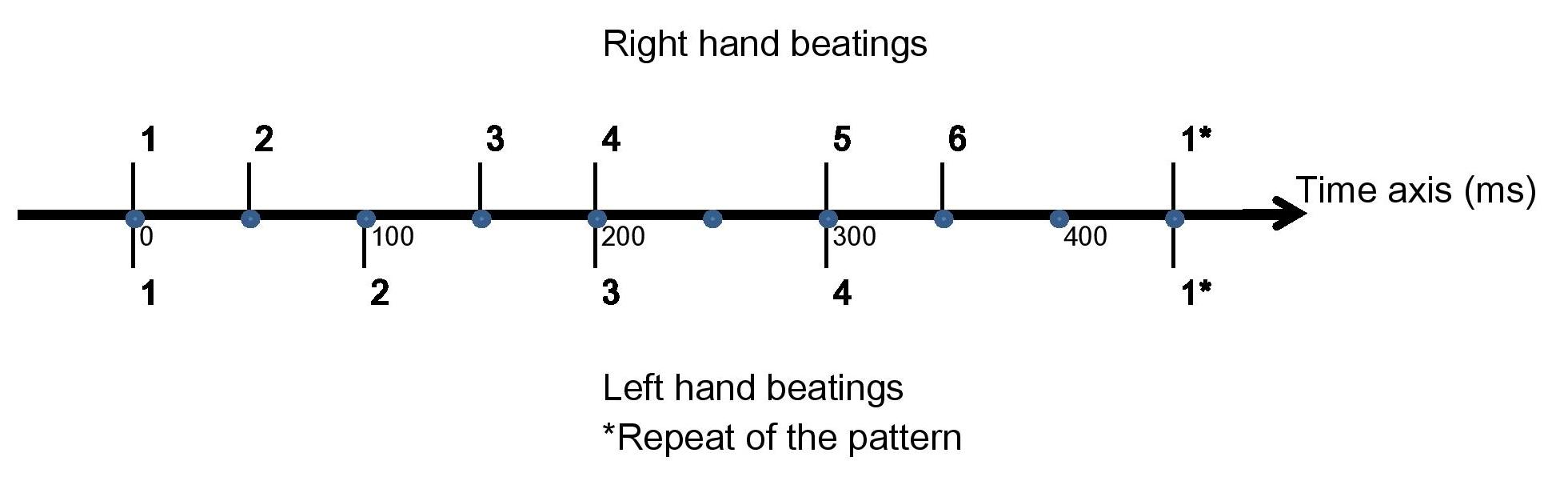

Referring to the schematic illustration of the pattern A of Barica (Figure 3), the polyrhythm is subdivided into cycle duration by the smallest isochronous interval to be timed, and successive taps from either hand on the appropriate beats is plotted on a timeline. The proper sequencing of the hands is guaranteed because the performer can consciously coordinate the fixed associations between the hands.

Figure 3 Schematic illustration of Barica, Pattern A. The upper line is the right hand beatings and the lower line is the left hand. They are plotted on a horizontal axis of milliseconds, the isochronous time interval of the polyrhythm between the left and right hand. (In R. Krampe, R. Kliegl, U. Mayr, R. Engbert and D. Vorberg, ‘The Fast and the Slow of Skilled Bimanual Rhythm Production: Parallel Versus Integrated Timing’, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 26/1 (2000), p. 207).

In order to understand what is going on in the examples of Youssouf’s performing and teaching, it can be useful to consult studies in experimental psychology on human movement timing. In an article by Krampe, Kliegl, Mayr, Engbert and Vorberg, two types of two-hand coordination, or more preferably bimanual control, in the execution of polyrhythms are identified: integrated timing and parallel timing. 8)Ralf T. Krampe, Reinhold Kliegl, Ulrich Mayr, Ralf Engbert and Dirk Vorberg, ‘The Fast and the Slow of Skilled Bimanual Rhythm Production: Parallel Versus Integrated Timing’, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 26/1 (2000), pp. 206–8. The authors explain how integrated timing only happens during initial practice at slower tempos. Here, conscious counting is allowed, meaning that the performer can count a sequence of varying interval durations. When speeding up, the bimanual technique is switched to parallel timing, and conscious counting becomes difficult. In this situation, the within-hands structure of the polyrhythm lends itself to timing out two isochronous sequences, one for each hand, performing two sequences of short and long durations independently (the anisochronous sequence). The perception of playing one syncopated polyrhythm becomes the playing of two anisochronous time sequences respectively and autonomously. Parallel timing is observed when balafon musicians improvise with two-hand coordination technique: each hand holds one mallet, the left hand plays the repetitive skeleton phrases, the right hand can perform improvisation on the rhythmic and melodic themes, or vice versa.

Video 3 Aly Keita performing an improvisation using two-hand coordination in the song Boro.

Confusion in learning the ‘rhythm’

Surprisingly, the teachers expected the students to comprehend the polyrhythm by listening to the integrated rhythmic layers and observing the physical coordination, but did not ask the students to first analyze the contrapuntal structure and practice each rhythmic layer independently (by each hand). This is one remarkable difference between the balafon and Western music in learning polyrhythm, as the latter always suggests students to delineate contrapuntal layers when learning polyphonic music. However, it is arguable that the balafon musicians ignore the contrapuntal relationship of a polyrhythm, because in two-hand coordination – the advanced independence coordination technique in executing polyrhythm – it is essential to recognize fully the syncopation of each independent rhythmic layer to synchronize the left and right hand. Interestingly, Youssouf did not consider the regular beat or pulse as a reference to understand time in music. Only reluctantly, he demonstrated the music indicating the pulse after one student explained that this was more effective to Western students.

Another example that demonstrates the different concepts of rhythm and metre regards a two-note pattern called ‘flam’. In the song Commis, the teacher showed us a rudimentary drum pattern that sounds like an ornamentation technique in classical percussion. He did not define how closely the notes should be played, other than that it sounds more like a ‘ghost note’ and was explained as ‘playing the two notes nearly together’. The students tried to tackle the right rhythmic logic by forcing the concept of a 32nd-note on the teacher, but he only suggested that they ‘listen well and imitate’.

Communicating the melodic materials

For the naming of melodic materials, the Bobo and Bamana musicians either sing the pitch they would like to express or play the wooden slat; they employ no names, symbols or letters to represent the identical looking wooden slats. 10)Naming or appointing family roles to wooden slats is present in other balafon cultures. Strand reports that in Sambla Baan, the southwest region of Burkina Faso, only 50 kilometres away from Bobo Dioulasso, the wooden slats of the instrument are given names, which may reveal the position of the slat within the scale or its function within a melodic or harmonic context. Strand, The Sambla Xylophone, pp. 164–73.

Usually, the teachers described the physical distance on the keyboard by indicating the number of wooden slats that the hand has to space out for the next note. When the consecutive do to re should be played, they would say ‘the next key on the left’, but for do to sol, which is spaced out by three keys, they would ask you to jump over two wooden slats or show you on the balafon. These difficulties have led me to metaphorically compare playing a melody on a balafon to two chess pieces jumping and joining different points tactically on a game board. As with learning rhythm, students learn melodic patterns by listening and imitating; only when more explanation is needed, do the teachers demonstrate the hand coordination slowly and repeatedly. 11)Interestingly, a similar phenomenon has been described in the study of popular music. Lars Lilliestam has used the phrase ‘playing by ear’ in his article to describe the oral transmission practice in popular music. By interviewing musicians of popular music, i.e. jazz and pop, he described how they communicate rhythmic and melodic concepts, the timing synchronization and their methods to learn and remember music without the aid of notation and written forms. See Lars Lilliestam, ‘On Playing by Ear’, Popular Music, 15/2 (1996), pp. 195–216. In another study, Johansson investigated the strategies used by rock musicians to identify unfamiliar guitar chord progressions. He suggested that ear playing is learned by doing it; a musician has to understand the music styles thoroughly, or embodied, so that he or she feels the chord progressions and formulas on an instrument and knows in what styles they are used, and the contexts in these styles. K.G. Johansson, ‘What Chord Was That? A Study of Strategies among Ear Players in Rock Music’, Research Studies in Music Education, 23 (2004), pp. 99–101.

Embodied movement as a vehicle of communication

A kinetic approach involving the coordination of both hands seems to be at the heart of learning the practice. From the lessons with the African musicians, the embodied movement becomes one visual representation to help communicating timing and melodic concepts, revealing the music in two dimensions: the vertical movement in the air represents time lapse and the horizontal spatial movement represents the melodic pattern.

Video 4 The top view of playing on the balafon, which clearly shows the horizontal spatial movement of a melodic pattern. Song Kebini performed by Youssouf Keita.

In spite of breaking up lengthy melodic patterns into groups of five notes, the teachers devised no specific method to help the students to digest the long phrase. They prefer the students to listen and imitate their movements; they always played on the student’s balafon and said, ‘Look! This is the correct way! [Playing on the balafon] This hand plays here [emphasized hitting motion and sound] and then, now comes this note’.

The same practice of transmission is also observed when Youssouf teaches his son some new balafon patterns by showing the hand movements except that whole process apparently needs no verbal explanation. 12)It is not surprising to ethnomusicologists that during the teaching process of African instruments, patterns of movement are imparted ‘physically’ by the teacher to the student. According to Gerard Kubik, a xylophonist in southern Cameroon teaches by holding his student’s hands and imparting direct impulses to them until the student has absorbed the movement pattern and stroke at the correct instant. (Kubik, ‘Pattern Perception and Recognition’, p. 227). James Koetting wrote about his experience with a Ghanaian who was asked to teach drum-playing to a group of university students. The students learnt and even performed the music largely based on the physical movements required to produce the music. See James Koetting, ‘Analysis and Notation of West African Drum Ensemble Music’, Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology, 1/3 (1970), p. 119.

Video 5 Youssouf teaching his son balafon patterns.

Musical notation vs. oral transmission

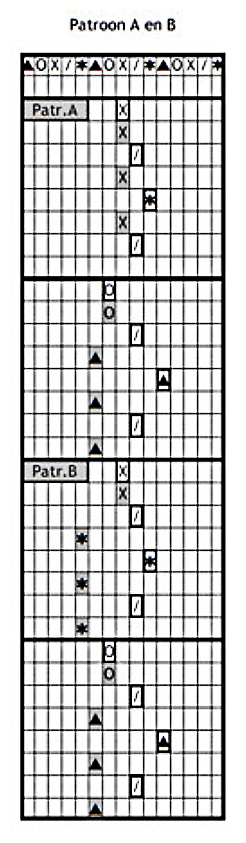

Participants in the workshop have used different methods to notate the songs we observed from the traditional musicians: Gert Kilian and others who are acquainted with Western music notation still have stuck solfège names on the balafon and use Western notation for transcription. Paul Nas, a balafon teacher from Holland has devised a notation system using symbols to identify pitch and grid squares to represent timing (Figure 6). 13)The notation is a close reminiscent of the Time Unit Box System (TUBS) developed from Philip Harlan in 1962. This system is widely used by ethnomusicologists, for example by James Koetting in his analysis of West African drum ensemble music. James Koetting, ‘Analysis and Notation of West African Drum Ensemble Music’, in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology, 1/3 (1970), pp. 115–46. The notation system used in Adrian Egger and Moussa Héma Die Stimme des Balafon (Hamburg: Schell Music, 2006) is another inspiration for Nas’s notation. The notation consists of one or more rows of boxes; each box represents a fixed unit of time. Blank boxes indicate that nothing happens during that interval, while a mark in a box indicates that an event occurs at the start of that time interval; supplementary signs indicate the technical skills of each instrument.

From the beginning stages of learning the balafon, I have adapted to learn and memorize the music by ear and observing the arm movements, so the Western solfège system is no longer a necessary tool for communicating the physical and conceptual knowledge during the lesson. If notation was preferred over oral transmission in the balafon practice, would it make a difference in the musical experience? The difference between notation and oral transmission is identified mainly in the conceptualization of the physical material – rhythm and pitch – when we learn music. We do use our ears in both cases, but when we read notation, music is translated in the form of notational signs – staff, notes and symbols. Sound is perceived as images visually; thus, notation becomes a finite, visible product that a performer can depend on in rehearsal and concert. When we learn orally and via imitation, music is no longer perceived through reading the visual symbols printed on score; instead, it is mediated by the embodied movement patterns of the teacher (or other persons who demonstrate the music) that transforms into the sound-producing movement of the performer.

Other information that learning holistically via oral transmission may convey is the practical know-how of creating music – the sound-producing movement of creating the timbre and interpretation. Notation and symbols provide the reciprocal concept in dynamics gradation, articulation, interpretation, melodic contour and time relationship; but the ‘knowing-how’ – the embodied sound-producing movement remains tacit and gives possibilities to diverse musical interpretations. In oral transmission, music is perceived via the embodied movement patterns and listening without other means of encoding of sound; it provides the information of ‘how’ to execute, more than the conceptual theory that only conveys ‘what’ to execute. For instance, in oral transmition, through observing the intensity of the arm movement, i.e. the height, speed and force of striking on the instrument, one can imitate holistically the physical production of rhythmic groove, timbre and dynamics of the music. When learning from notation, on the other hand, the musical qualities are communicated conceptually via symbols such as forte f, fortissimo ff and accentuation marks. In this latter way of learning, musicians still need to figure out the exact sound-producing movement to create the ideal sound qualities. In ‘Gestural Affordances of Musical Sound’, Rolf Inge Godøy discussed the splitting of music into a ‘score’ part and a ‘performance’ part due to the use of notation:

Western musical culture has been able to create highly complex organizations of musical sound with large-scale forms and large ensembles, thanks to the development of notation … we could claim that Western musical thinking often tends to ignore the fact that any sonic event is actually included in a sound-producing gesture, a gesture that starts before, and often ends after, the sonic event of any single tone or group of tones. In other words, Western musical thought has not been well equipped for thinking the gestural-contextual inclusion of tone-events in music … 14)Rolf Inge Godøy, ‘Gestural Affordances of Musical Sound’, in Musical Gestures: Sound, Movement, and Meaning, ed. by Rolf Inge Godøy and Marc Leman (New York: Routledge, 2010), pp. 109–10.

I am concerned that we have paid too little attention to sound-producing movement in learning and performing music; and for classical music, the tradition of notation reading has neglected that sound-producing movement is the actual action to create sound and music on our instrument.

Conclusions: Reflections on artistic improvements

After my encounter with the West African balafon culture, I have noticed positive influences brought to my artistic ability by following the oral and holistic approach, identified mainly in the aural skills of polyrhythm and the control of bimanual coordination. Somewhat paradoxically, I am enlightened with a clearer concept in the execution of syncopated rhythms by following the oral approach of the balafon culture. Without the assistance of graphical representation, I realized that the first priority in learning the music is to figure out the within-hands coordination when I observe the music pattern audibly and the embodied movement physically. This is the opposite of the classical music practice that music is already analyzed in the notated form by means of the Western rhythm system, which means, it already provides the coordination sequence of the two hands. As such, by practicing this holistic approach, the mind is trained to conceptualize the vague rhythmic relationship and builds up a stronger conceptual sense of isochronous timing (the smallest subdivision), which is crucial to maintain good bimanual control of polyrhythmic patterns. Gradually, the approach leads to a development of better bodily control of playing rhythm – the motor sense of bimanual rhythmic control. As a continuation from the last section, again, the within-hands coordination is a reinforcement observed from the change of perception of music from visual to motor sensory, since embodied movement becomes one vehicle of musical communication in replacement of notation.

My experience has provided alternative solutions to tangible performative problems, and the oral practice even aroused attention to missing ingredients that are essential to musical skills development and guided me to think beyond the formal Western practices. By practicing the balafon in these African educational settings, I (re)learn to be a (different) performer.

Footnotes

References

| ↑1 | The balafon I played during this field study is built by Youssouf Keita, tuned in pentatonic scale according to the Western temperament. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Participant-observation is a process enabling researchers to learn about the activities of the people under study in the natural setting through observing and participating in those activities. See Barbara Kawulich, ‘Participant Observation as a Data Collection Method’, in Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6/2 (2005), art. 43. It is believed to be one important research technique in ethnomusicology and related research subjects. John Baily emphasizes the importance of learning the Herati dutār and the Afghan rubāb is that it allowed him to understand the music from the ‘inside’. John Baily, ‘Learning to Perform as a Research Technique in Ethnomusicology’, in British Journal of Ethnomusicology, 10/2 (2001), pp. 85–98. John Blacking gathered valuable data through learning how to sing the Venda children songs with local teachers, as he could learn from mistakes immediately and began to learn what was expected of a singer and what was tolerated. See John Blacking, Venda Children’s Songs (Johnannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1967). |

| ↑3 | In the vast literature on African music, there are few discussions of the performance practice of pentatonic balafon; Gert Kilian and Eric Charry have described the instrument, the musical theory and the music culture, but they did not examine the embodied performance experience of the balafon musicians. See Gert Kilian, The Balafon with Aly Keita and Gert Kilian (DVD + booklet, Improductions, 2009) and Eric Charry, Mande Music (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000). Gerard Kubik discusses the perception of patterns and movement in relation to the recognition of rhythmic and melodic materials in African music, which he called ‘inherent patterns’. See Gerard Kubik, ‘Pattern Perception and Recognition in African Music’, in The Performing Arts: Music and Dance, vol. 10, ed. John Blacking and Joann Kealiinohomoku (The Hague: Mouton, 1979). |

| ↑4 | Moussa Dembele is a multi-talent musician; he plays balafon as his main instrument as well as kora and djembe. He is a cousin of the Keita brothers. He lived in the city Bobo Dioulasso in Burkina Faso in the same neighbourhood as the Youssouf Keita’s atelier, a reason why they often play concerts together. Moussa Dembele is now living in Belgium. Mandela (Oumarou Bambara) is a balafon musician from Bobo Dioulasso who now resides in Paris. I had some lessons with him during the second field trip, and he is an acquaintance of the Keita brothers. I further attended workshops with the European balafon musician Gert Kilian in France and Seydouba ‘Dos’ Camara from Guinea. |

| ↑5 | Kilian, The Balafon, Charry, Mande Music, p. 13. Julie Strand, The Sambla Xylophone: Tradition and Identity in Burkina Faso (PhD Dissertation, Wesleyan University, 2009), p. 256, has listed the gourd-resonated xylophones found in Burkina Faso according to the ethnic groups. |

| ↑6 | Kofi Agawu, Representing African Music– Postcolonial Notes, Queries, Positions (New York: Routledge, 2003), pp. 62–3 and 151–71. Further, Arthur M. Jones in Studies in African Music (London: Oxford University Press, 1959) wrote extensively on African rhythm in Ewe music, but reported that hardly any term in the Ewe language is found cognate to rhythm in English. |

| ↑7 | Charry, Mande Music, p. xxvii and p. 210, claims that he has not come across an extensive vocabulary related to rhythm. The Mande people are a large family of the ethnic group of West Africa who speak the Mande languages of the region. Mande groups include the Soninke, Bambara (Bamana), and Dyula. |

| ↑8 | Ralf T. Krampe, Reinhold Kliegl, Ulrich Mayr, Ralf Engbert and Dirk Vorberg, ‘The Fast and the Slow of Skilled Bimanual Rhythm Production: Parallel Versus Integrated Timing’, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 26/1 (2000), pp. 206–8. |

| ↑9 | Ruth Stone, ‘In Search of Time in African Music’ in Music Theory Spectrum, 7/1 (1985), pp. 139–48. Kofi Agawu, ‘Structural Analysis or Cultural Analysis? Competing Perspectives on the “Standard Pattern” of West African Rhythm’, in Journal of the American Musicological Society, 59/1 (2006), pp. 1–46. |

| ↑10 | Naming or appointing family roles to wooden slats is present in other balafon cultures. Strand reports that in Sambla Baan, the southwest region of Burkina Faso, only 50 kilometres away from Bobo Dioulasso, the wooden slats of the instrument are given names, which may reveal the position of the slat within the scale or its function within a melodic or harmonic context. Strand, The Sambla Xylophone, pp. 164–73. |

| ↑11 | Interestingly, a similar phenomenon has been described in the study of popular music. Lars Lilliestam has used the phrase ‘playing by ear’ in his article to describe the oral transmission practice in popular music. By interviewing musicians of popular music, i.e. jazz and pop, he described how they communicate rhythmic and melodic concepts, the timing synchronization and their methods to learn and remember music without the aid of notation and written forms. See Lars Lilliestam, ‘On Playing by Ear’, Popular Music, 15/2 (1996), pp. 195–216. In another study, Johansson investigated the strategies used by rock musicians to identify unfamiliar guitar chord progressions. He suggested that ear playing is learned by doing it; a musician has to understand the music styles thoroughly, or embodied, so that he or she feels the chord progressions and formulas on an instrument and knows in what styles they are used, and the contexts in these styles. K.G. Johansson, ‘What Chord Was That? A Study of Strategies among Ear Players in Rock Music’, Research Studies in Music Education, 23 (2004), pp. 99–101. |

| ↑12 | It is not surprising to ethnomusicologists that during the teaching process of African instruments, patterns of movement are imparted ‘physically’ by the teacher to the student. According to Gerard Kubik, a xylophonist in southern Cameroon teaches by holding his student’s hands and imparting direct impulses to them until the student has absorbed the movement pattern and stroke at the correct instant. (Kubik, ‘Pattern Perception and Recognition’, p. 227). James Koetting wrote about his experience with a Ghanaian who was asked to teach drum-playing to a group of university students. The students learnt and even performed the music largely based on the physical movements required to produce the music. See James Koetting, ‘Analysis and Notation of West African Drum Ensemble Music’, Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology, 1/3 (1970), p. 119. |

| ↑13 | The notation is a close reminiscent of the Time Unit Box System (TUBS) developed from Philip Harlan in 1962. This system is widely used by ethnomusicologists, for example by James Koetting in his analysis of West African drum ensemble music. James Koetting, ‘Analysis and Notation of West African Drum Ensemble Music’, in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology, 1/3 (1970), pp. 115–46. The notation system used in Adrian Egger and Moussa Héma Die Stimme des Balafon (Hamburg: Schell Music, 2006) is another inspiration for Nas’s notation. |

| ↑14 | Rolf Inge Godøy, ‘Gestural Affordances of Musical Sound’, in Musical Gestures: Sound, Movement, and Meaning, ed. by Rolf Inge Godøy and Marc Leman (New York: Routledge, 2010), pp. 109–10. |