Turning to Practice

Table of contents

DOI: 10.32063/0105

Erlend Hovland

Erlend Hovland (1963) is associate professor and head of the Ph.D. programme at the Norwegian Academy of Music (NAM). After music studies in Trondheim, Oslo, Paris, Basel, and Salzburg, he began his doctoral studies in 1990 at IRCAM, Paris. Hovland continued his research from multiple locations in Europe prior to defending his thesis on the orchestration of Gustav Mahler at the University of Oslo, where he later worked as a post doc. fellow on contemporary opera.

by Erlend Hovland

Music + Practice, Volume 1

Scientific

This fellow is wise enough to play the fool,

And to do that well craves a kind of wit.

He must observe their mood on whom he jests,

The quality of persons, and the time,

And, like the haggard, check at every feather

That comes before his eye. This is a practice

As full of labour as a wise man’s art,

For folly that he wisely shows is fit,

But wise men, folly-fall’n, quit taint their wit.

Shakespeare: Twelfth Night, Act III, Sc. 1

At a conference a few years ago, a British violinist played a concert program based on his reproduction of different playing techniques found in early recordings of treasured violinists. Portamento, glissando, vibrato, and a wide range of ornaments were borrowed from historical recordings and integrated into a historically informed performance of Beethoven’s violin sonatas. The puzzling thing was that even though this was an accomplished musician, and the audience at this particular conference appreciated the historical recordings of Fritz Kreisler and Carl Flesch, the concert could hardly be called a success. In piecing together different historical fragments, the violinist failed to create a coherent frame for the music. As a listener, one recognized the various stylistic borrowings from the historical models, but the result was an auditory patchwork of stylistic dissonances. The performance was neither modern nor historical, neither original nor conventional. The imitated figures were piled upon each other, lacking motivation or coherence. This says something about practice; but what, exactly, does it say?

Few would deny the fundamental importance of practices in music, and this without even having to pin down what we actually mean by the term. The notion of practice appears to be at once self-explanatory and unexplained. And if we subscribe to a traditional view and simply define practice as the opposite of theory,1)As found in Heinrich Schmidt’s much used Philosophisches Wörterbuch, 1951, where practice is simply defined as the ‘Gegensatz’ (opposite) to theory. the following critical questions seem inevitable: if theory is the condition for science, how can its opposite, practice, gain scientific value without merging it into a new form of theory? Must we not conclude that practice, important as it may be, falls in the blind zone, unfit for research, and becomes that of which we cannot speak? Admittedly, musicology is largely mute on the subject: practice has fallen outside its theories and categories.

Neglecting practice

But musicology has not been alone in its general neglect of practice. The shadowy existence of practice in scholarship is due not only to oversimplified definitions (cf. practice as the opposite of theory), but also to the way scientific disciplines are organized. Pierre Bourdieu’s statement that ‘[of] all the oppositions that artificially divide social science, the most fundamental, and the most ruinous, is the one that is set up between subjectivism and objectivism’, could be usefully applied to music as a field of professional engagement — torn between system and sensibility, schemas and skills, facts and feelings (Bourdieu, 1990: 25).2)‘Divided ruinously between objectivism and subjectivism’, social science is, according to Bourdieu, given a third path by a theory of practice. Research in music could equally profit from this same third path. The point is that practice must defy any stiff division between the subjective and the objective. Historically, an important ambition for musicology was objectivity; for many of its ‘ancestors and advocates’ in the nineteenth century, the model was the natural sciences.3)Characteristically, in the nineteenth century, historians and theoreticians such as François Joseph Fétis and Hugo Riemann, as well as the famous critic and ‘aesthetician’ Eduard Hanslick, were explicit in their preferences for the natural sciences as a model for musicology. This tendency towards objectivism and positivism laid the founding principles for the institutionalisation of musicology, which explains Joseph Kerman’s observation that ‘Musicology is perceived as dealing essentially with the factual, the documentary, the verifiable, the analysable, the positivistic. Musicologists are respected for the facts they know about music. They are not admired for their insight into music as aesthetic experience’, or, we might add, music as practice (Kerman, 1982: 12). The art and competence of a good practitioner — regarded as something highly individual or inspired by genius — were not included in the scope of musicology. And indeed, if practices were simply subjective and transient, they would hardly be a suitable topic for any research that seeks knowledge about them. On the other hand, if practices satisfied the categories and methods of musicology, practice studies would have become a dominant branch long ago. As it is, the conclusion must be that in order to make practice researchable, we need to look beyond the rigid divide between subjectivism and objectivism, and beyond the simplistic and dialectic opposition between theory and practice. This does not mean that objectivity and rationality have no place in practice studies. The objectivism that we criticize here is the automatic use of a standard set of scientific tools, which, without being questioned, serve as guarantees of truth and correct method.

Still, paradoxical as it may seem, the greatest threat to practice as a field of study is the lack of theory. To define and theorize practice is to create research potential. But since practice is inscribed in the concrete — in ‘real-world issues’ — there are good reasons to assume that different disciplines will have to develop differing theories and definitions, depending on the nature of the particular practice and the expectations held by those who pursue the research. For this reason, we need to unveil some of the terms and expectations with which we meet the research on musical practices.

As we see it, the legitimacy of practice studies in music is dependant on three assumptions: 1) practical knowledge is a means by which music exists and develops, 2) seeking knowledge must be the reason for doing research, but 3) if practical knowledge can be gained by other and already existing approaches, there is no reason for us to complicate the task by turning to new and premature forms of research.

Accordingly, our ambition for practice studies is to find a practical knowledge that is different from what we access through other methods and theories. We want to make musical practices researchable; and in order to achieve this, we need to elaborate theoretical perspectives from which musical practices can be studied on the terms set by the practice itself. We therefore need a theoretical outline that:

- explains how a practice can be studied,

- explains how a practice gains coherence, how it can be identifiable as one practice, without which it will hardly be a field of study,

- explains where it is ‘located’, and

- explains how knowledge production is a possible outcome of the study of practice.

This is not the occasion for a detailed discussion of recent literature on practice, but neither should we leave the issue altogether. The way we approach practice will dictate the outcome of our research, and, given our ambition for practice studies in music, there are good reasons to question some of the turns that recent practice theory has taken. We therefore need to look a little closer at some theoretical approaches to practice that are both widespread and seemingly relevant, but will not fulfil the ambitions we hold on the behalf of practice studies in music.

Two weary ways and a bogus bridge

The multitude of differing concepts of practice in recent social science, philosophy, and anthropology is overwhelming and leaves us with a challenge. A comprehensive presentation would require several dissertations, while a simple overview of the different ‘schools’ can at best provide a simplified classification without showing the reasoning involved. As we now will seek ways to think practice, without having to pass through encyclopaedic compilations, the solution will be to examine some texts where the thinking is both revealed and revealing.

The title of Theodore R. Schatzki, Karin Knorr Cetina and Eike von Savigny’s The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory echoes what has been known as the linguistic turn in twentieth-century theory. In addition to including contributions by many leading authors on practice, the book attempts to sum up some of the discussions about and positions on practice in the social sciences. The book’s strength is that it reveals the wide variety of ways in which ‘practice’ is understood; but though it gives an indication of the richness of academic investment in the subject, this variety makes defining practice a difficult task.

As we shall see, Schatzki’s article ‘Practice mind-ed orders’ is a good starting point for reflecting on practice. Intuitively, Schatzki’s definition of practice appears convincing, despite its lack of consistent and stringent terminology. In the space of five lines Schatzki gives three different explanations of what a practice is. First we read: ‘Practices are organized nexuses of activity,’ then he posits that practice is ‘an organized web of activity’, and, with no further delay, he continues with the statement: ‘[a] practice is, first, a set of actions’ (Schatzki, 2001: 48). By actions that compose a practice, Schatzki means ‘either bodily doings and sayings or actions that these doings and sayings constitute’. Now, obviously, we could comment on the unclarified use of the terms ‘nexuses’, ‘web’, ‘set’, ‘activity’ and ‘actions’. If anything, this illustrates the problem of framing practice in words. More interesting, however, is Schatzki’s use of the passive ‘organized’, which begs the question: ‘Who or what is doing the organizing?’ And further, is it the organization of a set of actions (i.e. bodily doings and sayings) that is the practice?4)To the last question Schatzki gives a clear confirmation — an answer that leads to several problematic questions concerning his use of organized activity, either in nexuses or webs. Is the simple fact that a set of activities are organized a sufficient explication for practice? Which activity can be defined outside practice, outside a possible organizable nexus or web? And how is a set of activities already there before the mind begins its organizing process? Schatzki does not answer these questions. One may argue that this reading of Schatzki is hair-splitting, but in this case, splitting hairs could prove important. The way we describe practice dictates our thinking and understanding.

One is likely to answer these questions in one of two different ‘ways’: either practice is seen from the point of view of an outsider, who presumably comes to the scene après coup, and who empirically observes and organizes, or practice is located in the mind of a person. The latter is the case for Schatzki. For him, the mind in question is not an abstract one, but the mind of a person confronted with a set of activities of which he or she tries to make sense. Making sense (and ‘mindedness’), in addition to the goal-directedness (and ‘purposefulness’) as well as the emotionality of a person, are what first and foremost organizes practice.5)‘Rules, however, only intermittently and never simpliciter determine what people specifically do. A more omnipresent determinant of practical intelligibility is thus called for. I incline toward drawing on Aristotelian-Heideggarian intuitions and identifying this third factor as a mix of teleology and affectivity. Teleology, as noted, is orientations toward ends, while affectivity is how things matter. What makes sense to a person to do largely depends on the matters for the sake of which she is prepared to act, on how she will proceed for the sake of achieving or possessing those matters, and on how things matter to her; thus on her ends, the projects and tasks she will carry out for the sake of those ends given her beliefs, hopes, and expectations, and her emotions and moods. Practical intelligibility is teleologically and affectively determined.’ (Schatzki, 2001: 52).

The other way, which Schatzki does not favour, leads towards an all-inclusive definition of practice. In the sociology of culture, dominated by Max Weber’s ideas and Talcott Parsons’ ‘values’, the turn to practice offered a much-needed option. According to Ann Swidler, the notion of practice ‘de-emphasized what was going on in the heads of actors’ (Swidler, 2001: 74). When the study of practice was proposed as an alternative to traditional sociology of culture, it implied a shift towards understanding practices as routine activities ‘notable for their unconscious, automatic, un-thought character’ (74).6)Swidler continues: ‘But whether “practices” refer to individual habits or organizational routines, a focus on practices shifts attention away from what may or may not go on in actors’ consciousness — their ideas or value commitments — and toward the unconsciousness — their ideas or value commitments — and toward the unconscious or automatic activity embedded in taken-for-granted routines.’ (Swidler, 2001: 75). Obviously, in this position there is no important difference between habits, routines, and practice. This led, however, to a position where actions, habits and routines are simply defined as practice. Practice thus becomes synonymous with activity. The near all-inclusiveness of this concept mirrors the similar error for which the old school of sociology was criticized: explaining everything with one model or concept, this time practice instead of ideas or values.

The analytical advantage of this second road, however, is the possibility of finding schemas. As Swidler writes: ‘Practices thus lie behind every aspect or level of social causation. And, as Sewell has argued, practices are enacted schemas, schemas which can be transposed from one situation or domain to another and which are expressed in, and can be read from, practices themselves’ (Swidler, 2001: 80—1). It is not the turn to schemas that is problematic, but the unwillingness to distinguish practice from activity, which easily establishes schemas as the firm and first ground upon which practice is defined (i.e. practice is what the schemas conceive as practice).7) And when Swidler explains how ideas and values were replaced by practices in the sociology of culture, this change is — at least according to her take on practice — accompanied by an opening of practice to nearly anything, even to ideas. It is thus hard to see how this notion of practice has actually changed the design of the social sciences. Schemas seem to have replaced the role of ideas and values as explanations for actions, but they have not altered the relation between researchers and their fields of study or the way knowledge is produced.

Now, the point is not to argue that these two approaches to practice are untenable. Our argument, rather, is that neither will meet our expectations of practice studies as presented above. What we seek is knowledge in practice. This is not to condemn scholarship that seeks knowledge about practice. Implicit in the choice of prepositions, here, is a different methodology and conception of the kind of knowledge one is seeking. In very general terms, the social sciences are seeking knowledge about practice. The directionality of the research is thus traditional. Researchers apply the standard scientific tools and methods, and practice simply ‘reports’ to those tools and methods. Practice thus becomes a topic for research, not a locus for a competing production of knowledge.

To these two roads to practice, we may add a third, which combines some of the characteristics of the others, though without building a convincing bridge between them. This approach is most likely founded on Aristotle’s philosophy and his concept of praxis. Alasdair MacIntyre’s work, in particular his Aristotelian distinction between praxis and techne (technique), is an excellent example of this third approach. Following this distinction, MacIntyre defines practice as ‘any coherent and complex form of socially established cooperative human activity through which goods internal to that form of activity are realized’ (MacIntyre, 1994: 187). Accordingly, he claims that ‘bricklaying is not a practice; architecture is … and so is the work of the historian, and so are painting and music’ (MacIntyre, 1994: 187). Socially conditioned, based on cooperation, and, not least important, containing internal goods, are thus the characteristics that define practice, and the examples could be any major socially existing phenomenon.8)‘Thus the range of practices is wide: arts, sciences, games, politics in the Aristotelian sense, the making and sustaining of family life, all fall under the concept.’ (MacIntyre, 1994: 187). It is possible, of course, to define music simply as practice of this kind, but doing so does not necessarily make music more accessible to research. Nevertheless, for MacIntyre, music is a practice because it is a human activity for which the goods or ends have to be continuously discovered and rediscovered. It is this unremitting search for its goods and ends that distinguishes practices from skills (or techne), and that brings the question of practice back to the playground of philosophers debating ideas of purposefulness, ends (i.e. ‘happiness’), morals and concepts (see MacIntyre, 1994: 273). But instead of bridging the gap between the two other roads (between ‘mind’ and ‘schemas’), this line of enquiry cultivates philosophical meta-theoretical reflection on the question of what constitute the internal goods and the ends of a practice. If it is a bridge at all, this one goes high above any muddy waters of the social, and will make no hand dirty.

We hold that neither the ‘mindless’, all-inclusive, and outwardly, nor the purpose-directed definitions of practice, are the most constructive for music, and — more important — it is hard to see how these definitions of practice can lead to a new and different kind of knowledge in music research. The scope is simply misplaced. Defining any action (or activity) as practice is too microscopic; defining music, art, and architecture in toto as practice is too macroscopic. And defining practice according to general terms such as ‘mindfulness’, ‘purposefulness’, or ‘affectivity’ can conceal the somewhat traditional endeavours such as a search for intentionality or hermeneutical meaning, or a classification of the world according to a set of beliefs or principles — all mirroring suspiciously well the gaze of the beholders and their academic field.

What these divergent approaches have in common is an attempt to plant practice in conventional scientific soil. Practice as knowledge, though, appears circumvented by an elliptic turn. Instead of being tackled where it is, it is dragged out from its shadowy realm and into the floodlight of conventional research strategies. What we need is a theoretical outline that can explain the way a practice functions without turning it into a hermeneutical quest, pure empiricism, or abstract (moral) philosophy, or reducing it to an abstract system, independent from the performing of acts and their articulation in a concrete and messy reality. This leaves us with the task of finding more suitable ways of studying practices — ways that will create research opportunities and reveal practical knowledge.

Other turns to practice

It is a well-used philosophical trick to draw on common vernacular usage to explore the meaning of a complex term, thereby seeking insight from everyday experience. Although there are good reasons to question what one actually finds by using this kind of demonstration, it is tempting to briefly remind us of how ‘practice’ is used in current language. We talk about practice as something we need to be initiated to: ‘to get or to have practice’, or ‘to be out of practice’. We use formulations like: ‘it needs practice’, ‘it takes practice’, or ‘it requires practice’. We also tend to conceive practice as a totality, which we may judge: ‘a good practice’, ‘a corrupt, unethical practice’, or an ‘unfair practice’, although it is not the moral judgment, as such, that then defines the practice. We further distinguish areas assumed proper to be considered as one practice, as we talk about a legal, medical, or religious practice, but still conceive law, medicine, and religion as disciplines or phenomena transcending practice.

Clearly, according to our everyday use of the word, we seem to comprehend practice as something more than (a random collection of) actions or automatic movements. It is something we continually need to ‘practice on’, something we perceive as an identity or as having intrinsic quality. In fact, our use of the word practice in everyday language seems to embrace a complexity that is theoretically hard to pin down. Despite this, let us try, bearing in mind that this attempt is only one among many possible.

We will now look at two outlines or positions that combined may serve as a point of entry to practice studies, bearing in mind that our object is neither to close the matter once for all, nor to discuss or present in any sufficient way the content of these positions. These two positions are first and foremost illustrations of ways to approach the study of knowledge in practice. It is the dynamic thinking, a result of the combination of these two positions, that is our concern, not the theories as such. And knowing well that we could find other entrances that could create a similar approach to practice, this gives rise to a suspicion. Should theory be anything but metaphorical descriptions of thinking in practice?

The linguistic turn

Comparing practices with languages has some obvious advantages. According to our preconception of practices, the apparent similarities between the phenomenon of language and the phenomenon of practice are striking. Practices, like languages, are shared or sharable. (The notion of a one-man language is nonsense). They are constructed in community; they are social products. Like languages, practices may also be means of communication. Both are comprehended as something distinguishable — a whole — despite their blurred distinctions towards other practices, systems of sign, means of mediations, etc. Practices, like language, are also in constant development; they bear the imprints of time and place.

Few of us are able to explain how a language works; nevertheless, as native speakers we are capable of mastering its complex underlying principles. And mastering these principles is necessary in order to be understood, to be able to communicate, and further, to express nuances and complex reasoning. This is in many ways analogous to the abilities of competent practitioners and their relation to practice. To say, however, that practice resembles language is to ignore that it might be the other way around. In fact, many would regard language itself as a practice.

The distinction between speech (parole) and language (langue), on which Ferdinand de Saussure (1857—1913) built his linguistic theory, has profoundly influenced linguistics, philosophy, practice theory, and even computer science and neuroscience. According to Saussure, speech is what we ‘do’; it is the executive side. Speech is always individual, ‘for execution is never carried out by the collectivity’, and the individual is always master of it. Language (langue), on the contrary, is not itself ‘a function of the speaker. It is the product passively registered by the individual’ (Saussure, 1983: 14). In fact, if anything could be called a linguistic ‘Columbus’s egg’, it must be this distinction between speech and language.9)Saussure’s theory was not entirely original. According to Noam Chomsky, Roger Bacon, Nicolas Beauzée, and John Stuart Mill, had all played with the idea of a some general principles prior to all languages, principles that ‘are the same as those that direct human reason in its intellectual operations’, according to Beauzée (Chomsky, 1985: 1). By defining language (langue) as natural to man (that is ‘the faculty of constructing a language, i.e. a system of distinct signs corresponding to distinct ideas‘), Saussure debunks our commonsensical ideas — likely to claim speech as both natural and primary — and in so doing he offers a better model for linguistic research (10). Language is thus defined as the precondition of speech; it is a system of objective relations, a structured system or, rather, a structuring system (10).

The Columbus factor is obvious: The Saussurian notion of language (langue) is something we cannot ‘see’ but must assume exists in order to explain languages. The assumption that there is a natural capacity of our mind (i.e. ‘faculty’ or ‘a grammatical system existing potentially in every brain’) that accounts for the construction of language has become a much-researched topic in both linguistics and neuroscience. These points may also be relevant for practice studies, as they provide an alternative model for understanding how practice works — how we can assume order in practice — but they also may suggest that we have a mental faculty that predisposes us to the construction of practices. Although Saussure defines this faculty as human, not individual, he also claims that language is social, constructed in community. All this chimes well with our understanding of the nature of practices.10)‘It is the social part of language, external to the individual, who by himself is powerless either to create it or to modify it. It exists only in virtue of a kind of contract agreed between the members of a community.’ (Saussure, 1983: 14).

One may object that practice and language are not identical phenomena, and, for this reason, it is invalid to conceive practice as language, in the Saussurian sense. But this objection misunderstands our intention (even if we leave aside the highly relevant hypothesis that practices and languages are in many aspects similar). Our turn to linguistic theory is an attempt to find a model that can make practice researchable. The linguistic path does, to some degree, answer our search for an explanatory model, a model that suggests that a practice can be analyzed by finding its underlying ordering principles, or its structuring system.

The advantage of the model is that it may explain why a simple set of performed acts does not as such reveal how a practice functions — how it is perceived as one practice. It also proposes to explain why a good practitioner is rarely capable of articulating the way a practice is organized, in the same way we are hardly capable of explaining how the language we speak functions on a deeper level.11)Similar statements are found in the literature of both practice research and performance studies. As Richard Schechner says: ‘It is also true that only a few masters will be able to formulate in words the grammar of whatever performance genre they practice, be it kathakali, ballet, rock music, baseball, noh, or shamanism. Most performers will not be able to articulate precisely what they do, even if over time they get better and better at doing it.’ (Schechner, 2006: 233). Interestingly, if we rephrase Saussure’s definition of language, we have a definition of practice that comes close to meeting our initial criteria: Practice is a structuring system, a self-contained whole and a principle of ordering at the same time.12)‘A language as a structured system … is both a self-contained whole and a principle of classification.’ (Saussure, 1983: 10). But as soon this is said, we can turn Saussure against both himself and us when he states that ‘no word corresponds precisely to any one of the notions we have tried to specify above. That is why all definitions based on words are vain’ (1983: 14). In fact, Saussure claims that it is ‘an error of method to proceed from words in order to give definitions of things’ (14). This slightly excruciating comment is nevertheless highly relevant. First, it illustrates the shortcomings of conventional approaches to research, in which the subject matter is simply accommodated to the previously established vocabulary and methods. Second, it is even more relevant for practice studies, since our ‘objects of study’ are likely to be far less identifiable than the components of language. What we have are acts — acts that as such lack the conceptual clarity of spoken words and sentences (that is the ‘executive’ side of language, the speech). The acts of a practice (and their internal relationship) cannot be comprehended without grounding the research in the messy, real world, where the performance of the act unfolds.13)Tempting as it is to ascribe the highest degree of scientific value to the model that is most abstract and general, it is important to recognize that practice research will lose its raison d’être if it should be dissociated from the actual messiness of the practice, its performed activity. And further, as our ambition is to find a theoretical outline for the studying of practicalknowledge, we cannot be satisfied by simply proposing an abstract structuring system. The knowledge that we are seeking must be found in the practical encounter with the world. That is why the actual performing of acts is vital to our research.

The performative turn

The performative turn has led to several notorious theoretical positions or spin-offs, such as Richard Schechner’s coining of ‘performance studies’ and Judith Butler’s ‘performativity’. The latter represents an important branch in contemporary gender studies, while the former combines theatre studies, anthropology, and philosophy in a bold attempt to explain the omnipresence of performance in all walks of life. We shall here, however, rather focus on some of the precursors of this turn, and more precisely, on the terms, ‘énoncé’, ‘enunciation’, and ‘performative’.

Émile Benveniste, who in many ways built his position on Saussure’s linguistic theories, nevertheless saw that a semiotic system of differences alone could not create meaningful communication. One needs the concrete act in order to reach a semantic level. Benveniste’s solution was to proffer a distinction between énoncé and enunciation, (a conceptual pair faintly echoing the Saussurian language/speech), in which énoncé is the statement independent of context, whereas the enunciation is the act of stating as tied to context.

The term ‘performative’ was first used by J. L. Austin, and presented in the posthumously published lectures How to do things with words (1962). The term was first used to describe certain utterances that actually performed actions (‘I hereby pronounce you husband and wife’).14)‘The term “performative” will be used in a variety of cognate ways and constructions … The name is derived, of course, from “perform”, the usual verb with the noun “action”: it indicates that the issuing of the utterance is the performing of an action – it is not normally thought of as just saying something.’ (Austin, 1962: 6—7). Both Austin’s term, performative, and his Speech Act theory were picked up by John Searle, and resulted in a new philosophical awareness of how speech acts.

But our ‘object of study’ is not language, but music. This makes the performative aspects at once more self-evident and more problematic. There can be no doubt that we tend to emphasize énoncé rather than enunciation when we talk about music. Few of us would actually say that the meaning of a Beethoven symphony lies in the actual performance, and not in the ‘music itself’. (Despite the fact that the énoncé level in music is highly abstract, likely to be associated with some variants of structure. In fact, what are the ‘statements’ that music actually performs?) The essentialist thinking in music, persistent as it is, may to a large extent also explain why neither performance studies nor practice studies have made significant inroads in music research. Or, to put it differently, we do not emphasize the performative aspect of the act: how to do things with music. The act is likely to be considered as representative, whether of intentionality, score, school, tradition or some (emotional) state of mind. Now, the point for practice studies is not to decline the representative function of the act, but also to judge the act as performative — that is, on the basis of what it actually does, as well as what it represents. This double turn of perspective is likely to tell a different story, a story that in fact introduces ‘practice’.

The essentialist point of view is not the only one with which we have to struggle. Although acts of music lack the ‘clarity’ and articulation of spoken language, it would be a gross simplification to call them tacit. They are articulate — acts always are — but in a different way, which is to say, within a practice. In order to study this articulation, we need to be familiar with the ‘speech’; we need to understand what is spoken in this ‘language’. If not, we will have an equation formed of unknown entities. To put it bluntly, in order to understand how a practice is constructed, one needs to understand what it ‘says’ when it ‘speaks’.

Underlying our argument for a performative turn is a claim that there is no vantage point outside the practice that can reveal its ordering principles. We need to focus on both how an act is performed and what it performs inside the practice. This requires an approach from within the practice, one that can redirect or challenge the conventional academic position from outside (practice).

We believe that these two turns (i.e. the ‘linguistic turn’ and the ‘performative turn’) provide two possible outlines for a theory of practice. With these two turns we have a model not only for seeking the ordering principles beneath the chaotic surface of a practice, but also for taking into account the plenitude created by the performance of an act. Still, how is it possible to combine these two highly different positions in research? Systems, objective relations, ordering principles are all expressions that bring forth ideas of strict control, compulsory decisions and even punishment, while performance and act are easily associated with the transient, the fugitive and the contextual. There is an apparent conceptual dissonance between these two models that demands some kind of resolution.

The resolving power of frail logic

A resolution is possible if we accept that the ordering principles in a practice are idiomatic (or should we dare a neologism, ‘praxiomatic’?) That is to say that a practice has its own ways of forming successions and inherent relations, and further, that this process of formation must be related to how acts are actually performed and not to general or abstractly constructed schemas.15)Foucault states that the discourse (le discours) is a practice that has its own forms of sequence and succession (‘qui a ses formes propres d’enchaînement et de succession’) (Foucault, 1969: 221). Similar statements and observations can be found in the writings of de Certeau and Bourdieu. Methodologically speaking, acts inform order, and order forms acts. To analyse and describe this order is to study the inherent qualities of a practice. It is to find how a practice works, and how it gains a heuristic quality as something identifiable. Moreover, describing these inherent forms of succession and internal relations can be a major step in divulging a practical knowledge.

Let us take driving a car as an example. All the science in the world, explaining in detail the way technology operates the vehicle, the physical reality involved in driving, the rules of traffic, even the psychology of driving, will not make you able to drive a car. When you finally get your licence, your knowledge of theory and traffic rules is probably at its peak, while your ability to actually operate in traffic is at its lowest ebb. Gradually, as you learn the practice, you develop an amazing ability to control the car: you make the car an extension of your body, and you operate in complex urban surroundings where the mass of information is overwhelming. At the same time, you develop an ability to recognize instantly what is important, what needs to be given attention and what can, if the surface is not slippery, the evening light not deceiving, be ignored. Even more impressive, you recognize and can deal with the behaviour of other drivers. You recognize instantly different attitudes within the practice. The driving practice of others is an entity you evaluate as comprehensible and calculable. And yet, the practice of driving is regionally, geographically and socially conditioned. Driving a car in Rome is quite different from driving a car in Oxford or in snowbound Haparanda. So, learning the theory of driving is the easy part. What a driver needs is practice, in the double sense of the word. The best teacher is the one that makes you aware of practice, gives you tools in order to appropriate the way the practice functions, and who makes you understand its logic.

This last word might be surprising. And yet, throughout history, theoretical discussions of practice have returned to the words ‘logic’ and ‘rationality’. For Petrus Aureoli (1280—1322), logic was an example of how the intellect plays an active and regulating role in practice (Ritter, 1989: 1290), whereas Aristotle’s concept of practice emphasised rationality. This also explains the background for Bourdieu’s thinking, when he claims that practice ‘has a logic which is not that of the logician. This has to be acknowledged in order to avoid asking of it more logic than it can give …’ (Bourdieu, 1990: 86). According to Bourdieu, this practical logic is ‘able to organize all thoughts, perceptions and actions by means of a few generative principles, which are closely interrelated and constitute a practically integrated whole, only because of its whole economy, based on the principle of the economy of logic, presupposes a sacrifice of rigour for the sake of simplicity and generality …’ (86).

In fact, it is the poverty of the logic that will resolve the dissonance created by regulating principles and the necessary attention given to the particularity and ‘reality’ of the performed act. In order to deal with the complex reality in practice, one has to cope with an abundance of information and choices. Let us return to our example of driving a car in a busy city street. The ‘poverty’ of the logic here lies in the fact that one cannot pay attention to every detail and assess consciously every bit of information in strictly formal logical terms. One is forced to organize the complexity according to some generative principles (hence ‘economy’), which cannot explicitly cover in detail every particular situation. A general lack of precision and strictness makes the logic frail, but it is both necessary and a guarantee of efficiency. To find these generative principles is to explain how a practice functions, how it can be comprehended as a dynamic entity, and how it is capable of dealing with constantly changing circumstances.

We could talk about the operationality of a practice, by which term we mean the way a practice develops efficient and broad-spectrum generative principles. If the principles are too many and too specific, the practice will lose operationality. The practice’s operationality is dependent upon its economy; a practice with relatively few, but well functioning principles, is likely to perform a high degree of operationality. Yet too few generative principles will not be sufficiently precise to cover every possible situation in which an act is performed. Efficiency comes with a cost: a poor but practical logic.

Insight and blindness

As we have seen, there are multiple ways to define practice. For some, practice is understood as ‘well-functioning routines’ (Kreiner and Scheuer, 2002: 15), while others define both individual habits and routines as practices, thereby stressing the ‘unconscious and automatic activity embedded in taken-for-granted routines’.16) See endnote 6. Again, we may claim that when the definition of practice tends to include any unconscious action, its ability to reveal knowledge inpractice will be limited. And yet it is not always possible to draw an absolute distinction between routines, automatic activity, habits, on the one hand, and practice, on the other; nor is such a distinction necessarily something to wish for. In music, automatic activities, routines and skills, are necessary preconditions for most practices, and often simply comprehended as technique.

Not all activity is practice. Many of the actions in playing an instrument are deeply embedded in internalized and reflexive bodily actions; they have become second nature of the musician. So, drawing a clear-cut distinction between these bodily movements and practice is, for good reasons, not always possible. However, we may claim that internalized movements as such are not practices, but bodily acts through which practice may be articulated. Or rather, these bodily movements are the means through which a practice ‘articulates’, in the same way as the subtle production of sound by the human voice is not the language as such, but a means by which language is possible. This does not belittle the importance of technique and skill in music or in practice. In fact, the relation between technique and practice in music is particularly interesting and multilayered.

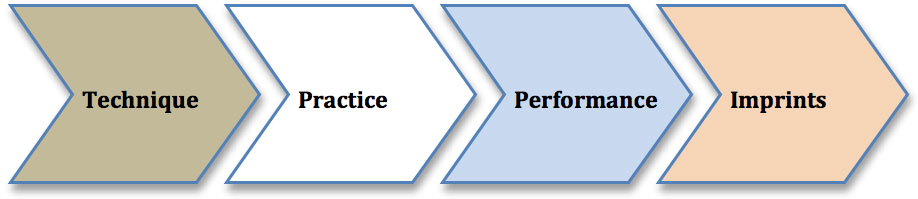

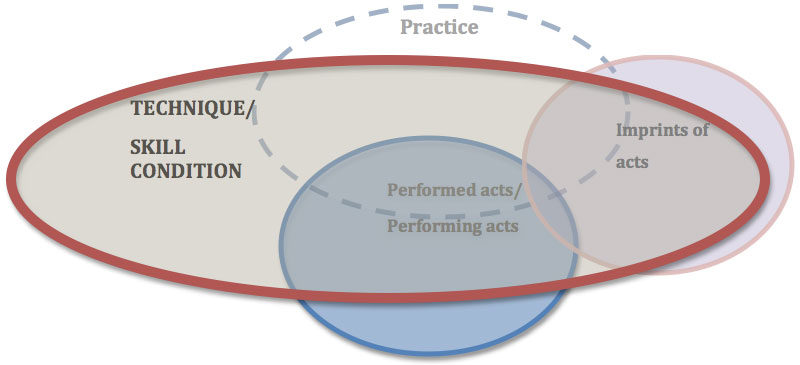

Taking these considerations into account might lead us to the following model (Figure 1), which shows how practice might be regarded as something both depending on and reflected through other instances of activity. Of course, the function of the figure is to represent, in a very simplified manner, a relationship that can be presented as a sequence.17)It has, however, the inconvenience of suppressing both a far more complex chain of correspondence between the different links and the influence and participation of any other cultural, social or technological phenomenon.

We thus have a sequence from what we can call the skill conditions (‘Technique’) to practice, to the performing of acts or acts performed (‘Performance’) and the documentation (‘Imprints [of acts]’). In this sequence, ‘practice‘ is the link placed in the middle of a process going either from potentiality to realization, motion to act, or technique to performance, and which, finally, leads to imprints of acts or documentation. In this figure, practice is the only link that has no material or physical presence.

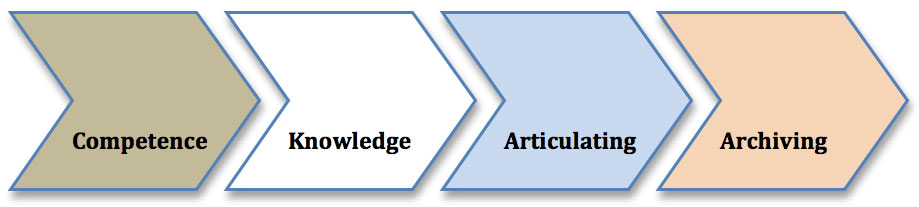

A parallel model (see Figure 2), focusses on the research-related qualities of each link — on what the practitioner and researcher could have, do, or find:

Related to technique and skill conditions we find competence. Related to practice we have knowledge, or rather practical knowledge. Related to performance we have articulation (or enunciation, if we should repeat the terminology of Benveniste). And related to imprints we have archiving or documentation.

As a demonstration, these simplified models explain how our understanding of practice can depend on where our attention is focussed. What we here call technique/competence can also be what Swidler defines as practice (‘unconscious and automatic activity embedded in taken-for-granted routines’), or what MacIntyre defines as skills. The position of Schatzki (‘set of actions’ and ‘making sense’) is mainly describing practice as ‘performance’/‘articulation’, whereas much of the performance practice (e.g. the Early Music Movement) use of historical sources focusses primarily on the ‘imprints of acts’ (‘archive’ or ‘archiving’) and not necessarily the study of a historical practice per se.18)Interestingly, this model also finds support in Saussure’s definition of ‘Speech’, where both the performative (and necessarily individual part) is in the following citation marked by (1), and what we have called ‘technique and skill conditions’ is marked by (2): ‘Speech, on the contrary, is an individual act of the will and the intelligence, in which one must distinguish: (1) the combinations through which the speaker uses the code provided by the language in order to express his own thought, and (2) the psycho-physical mechanism which enables him to externalise these combinations.’ (Saussure, 1983: 14).

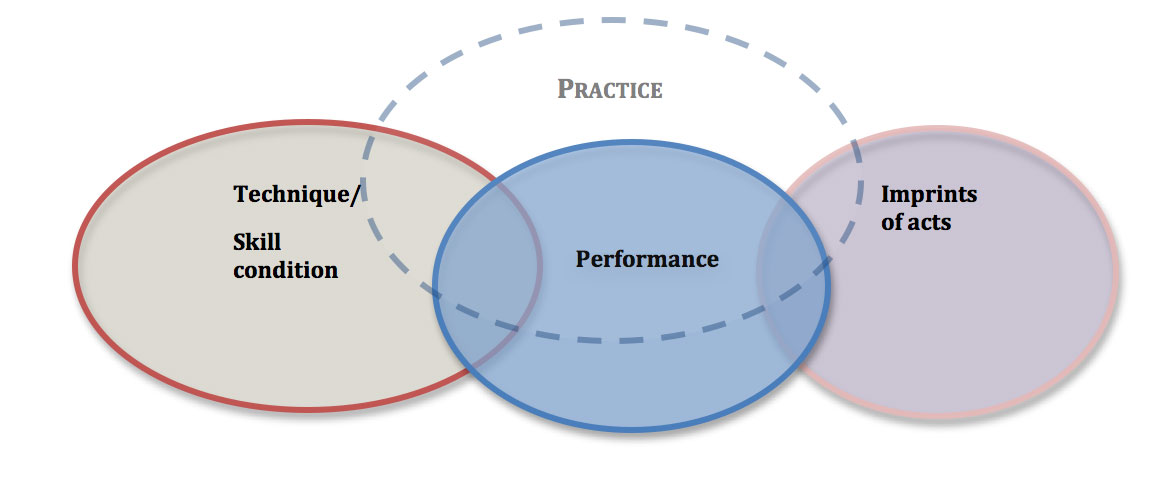

Of course, the simplicity of this model is also its weakness. By representing the model as a track from technique to performance, we ignore the fact that influences and ‘cause and effect’ are far more complex. And the model presents the links as clearly distinguishable, which they are not. We might therefore rearrange the figure so that, instead of links in a sequence, we have discs that overlap in varying degrees (see Figure 3). The ‘practice disc’ is in stippled line, indicating its lack of direct physical presence. The figure also shows that practice may overlap with all the other discs, but still, each of the discs has its proper field. The existence of an area of practice, which does not overlap any of the other discs, could also indicate its openness to what we could call a superstructure, consisting of — for example — other social and cultural practices.

If these models achieve any clarity, then they have a purpose. The relation between technique and practice is complex, however, as technique is not only a precondition for practice, but may also be a reply to what a practice demands. In most cases, we access practice only through ‘acts performed/performing acts’ or ‘imprints of acts’. We then need to (re)construct what, precisely, constitutes a practice or its technical preconditions. Of course, to maintain a distinction demands a methodological effort, but a necessary one, as the alternative is to lose sight of our main object, the study of practical knowledge, and can easily result in replacing practice with technique, performed acts or imprints of acts.

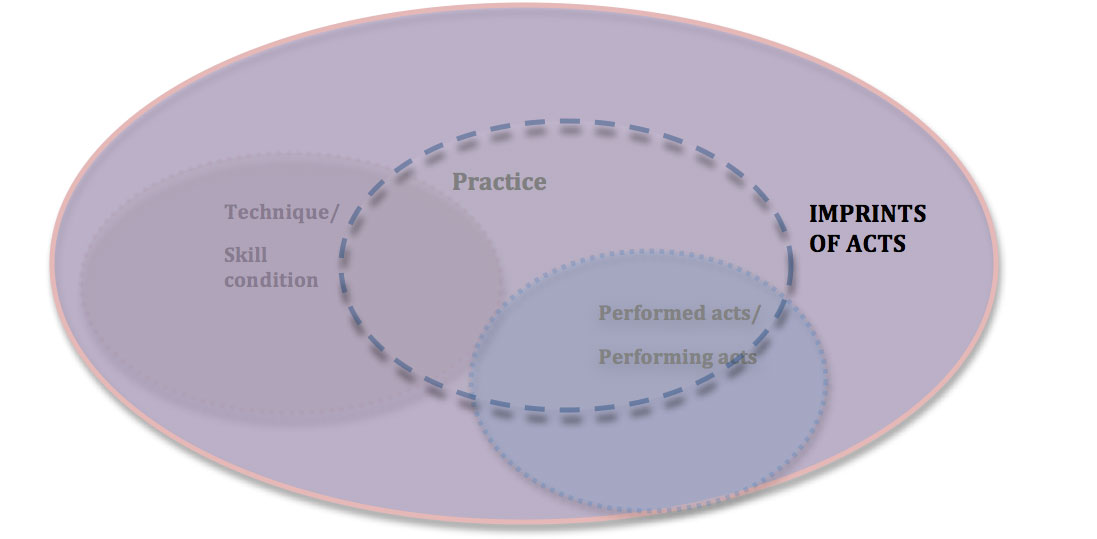

Still, it is neither in the idealized sequenced form nor in the overlapping and more complex disc form that we normally comprehend or meet practice. If we focus on what we actually see as researchers or practitioners, the model can be completely refigured (see Figure 4). For an archaeologist, the last disc (Imprints) would dominate totally. The existence of the other discs is methodologically hypothesized, and is to a large degree what the research is about.

A similar presentation of the dominance of the last disc could also exemplify the approach of a researcher/practitioner of Historically Informed Performance Practice. But contrary to the archaeologist — at least if we can accept the critique of Taruskin — this researcher/practitioner was less interested in uncovering the other discs, and more inclined to update these with present-day standards (see this issue’s editorial). Undoubtedly, Taruskin’s critique was based, when it was stated more than 30 years ago, on good observation. But even if we concede Taruskin some valid arguments, we must not forget that we are always under the inevitable spell of the present-day. Our methodological claim, however, is that a higher degree of awareness of the way we inevitably colonize historical music with our own contemporary practice (and technique), can redirect our attention and better uncover historical practical knowledge.

If we take another example, the view of the contemporary ‘mainstream’ musicians (if this is a valid term anymore) and their activity as performers, we may refigure the discs so that the first, the technique and skill conditions, is the most dominating one (see Figure 5). If that is the case, what is understood by the colloquially used ‘practice’ is in fact mainly technique.

Commentaries on the figures

These different figurations of the model, each emphasizing one of the discs give a simplified presentation of why practice means different things from different points of view. The one disc that is hardly ever emphasized is the one we actually label ‘practice’; and this is understandable: as we have already stated, this is the one that is only indirectly accessed and that lacks materiality. These possible refigurations illustrate not only how practice is easily circumvented by an elliptic turn, but also how it may be eclipsed by one of the other discs. The refigurations further explain how we can seemingly talk about the same topic, practice, but have quite different approaches to and views about what it is, all depending on our professional engagement in music.

Even though the point of our argument is to prioritize practice as an area of research, it must be stressed that all related subareas are of decisive importance for the study of practice. In most cases, what we know of technique/skills is underdeveloped and unarticulated. The performed/performing of acts is another field that both lacks methods (and to some extent, a relevant vocabulary) and demands great awareness. Imprint of acts is also a field that has been insufficiently explored, and must be both found and presented properly, either by ‘excavating sources’ (often the case with historical music) or finding ways to document practices that have weak imprints.

And yet, this presentation of practice has several obvious flaws. It leaves hardly any place for the individual. It also suppresses the complex relation between practices and the cultural, social and ‘ideological’ superstructure; in other words, the ways practices both reflect and partly constitute this superstructure. Neither does it account for temporality – how practices are created, how they change, refigure, succumb, etc. And of course, the list of flaws could be made much longer.

Some concluding remarks

It is hoped that some of the arguments and outlines sketchily presented in this article might point in the direction of a practice study in music. What is certain is that future practice studies will both challenge the arguments and claims presented here, and contribute many new ones. The nature of the topic demands a plurality of pathways, of critical and dissonant voices, of researchers and practitioners with highly differing views. If practice studies are to make a substantial contribution to how we understand and research music, it must embrace a wide variety of approaches, some occupied mainly with technical skills, others with describing the historical background, technological conditions, social function, routines, traditions, and so forth, all of which are necessary ingredients in an accomplished and developed research. But all this is to come. Now we need to accept the fact that practice studies in music has great potential, but needs our attention and effort to become a new and mature way of doing research in music.

As we have seen, despite the need for a theoretical reflection on practice, the purpose of this article was not to give an ideal, philosophical definition of practice, nor to insist on the necessity of finding a common understanding of practice. On the contrary, the theoretical claim underlying this text is that we need to focus on what we can study as practice, and how we can seek a practical knowledge inside practice. To some extent we turn things around. It is the way we can study practice and find a practical knowledge that defines the concept.

But what about the British violinist who had the dubious honour of opening this article? If his aim was to produce a correct and truthful rendering of stylistic aspects of the historical recordings, he did not succeed. The attempt meticulously to replicate the historical figures was not supported by an understanding of how these figures were acts in a practice where they had expressive and formal functions. By transposing them to a modern historically informed performance, based on metronomical, plain playing, they were rendered unconvincing. The problem was that the violinist was no more concerned with practice than an archaeologist carefully digging up some relics and bringing these in to a museum, without providing any information or setting the pieces in a context, without caring for a meaningful presentation. The Englishman not only mistook archive for acts, but also acts for facts. But facts are not the words that practice speaks. Which leads us back to Shakespeare: In practice, fools we are. Either we know to play, or fooled we stay.

References

Austin, John L.. 1962. How to do things with words (New York: Oxford University Press)

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. The Logic of Practice (Cambridge: Polity Press)

Certeau, Michel de. 1990. L’invention du quotidian, I: Arts de faire (Paris: Gallimard)

Chomsky, Noam. 1986. Knowledge of language: its nature, origin, and use (New York: Praeger)

Foucault, Michel. 1969. L’archéologie du savoir (Paris: Gallimard)

Kerman, Joseph. 1982. Musicology (London: Fontana)

Kreiner, Kristian and Steen Scheuer (eds). 2002. Forskning i praksis: artikelsamling (København: Nyt fra samfundsvidenskaberne)

MacIntyre, Alasdair. 1994. After Virtue: a study in moral theory (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press)

Saussure, Ferdinand de. 1983. Course in General Linguistics (London: Duckworth)

Schatzki, Theodore R., Karin Knorr Cetina and Eike von Savigny (eds). 2001. The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory (London and New York: Routledge)

Schechner, Richard. 2006. Performance Studies: an Introduction (New York: Routledge)

Schmidt, Heinrich. 1951. Philosophisches Wörterbuch (Stuttgart: Kröners Taschenausgabe)

Swidler, Ann. 2001. ‘What anchors cultural practices’ in The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory, ed. Schatzki, Cetina, and Savigny (London and New York: Routledge)

Footnotes

References

| ↑1 | As found in Heinrich Schmidt’s much used Philosophisches Wörterbuch, 1951, where practice is simply defined as the ‘Gegensatz’ (opposite) to theory. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | ‘Divided ruinously between objectivism and subjectivism’, social science is, according to Bourdieu, given a third path by a theory of practice. Research in music could equally profit from this same third path. The point is that practice must defy any stiff division between the subjective and the objective. |

| ↑3 | Characteristically, in the nineteenth century, historians and theoreticians such as François Joseph Fétis and Hugo Riemann, as well as the famous critic and ‘aesthetician’ Eduard Hanslick, were explicit in their preferences for the natural sciences as a model for musicology. This tendency towards objectivism and positivism laid the founding principles for the institutionalisation of musicology, which explains Joseph Kerman’s observation that ‘Musicology is perceived as dealing essentially with the factual, the documentary, the verifiable, the analysable, the positivistic. Musicologists are respected for the facts they know about music. They are not admired for their insight into music as aesthetic experience’, or, we might add, music as practice (Kerman, 1982: 12). |

| ↑4 | To the last question Schatzki gives a clear confirmation — an answer that leads to several problematic questions concerning his use of organized activity, either in nexuses or webs. Is the simple fact that a set of activities are organized a sufficient explication for practice? Which activity can be defined outside practice, outside a possible organizable nexus or web? And how is a set of activities already there before the mind begins its organizing process? Schatzki does not answer these questions. One may argue that this reading of Schatzki is hair-splitting, but in this case, splitting hairs could prove important. The way we describe practice dictates our thinking and understanding. |

| ↑5 | ‘Rules, however, only intermittently and never simpliciter determine what people specifically do. A more omnipresent determinant of practical intelligibility is thus called for. I incline toward drawing on Aristotelian-Heideggarian intuitions and identifying this third factor as a mix of teleology and affectivity. Teleology, as noted, is orientations toward ends, while affectivity is how things matter. What makes sense to a person to do largely depends on the matters for the sake of which she is prepared to act, on how she will proceed for the sake of achieving or possessing those matters, and on how things matter to her; thus on her ends, the projects and tasks she will carry out for the sake of those ends given her beliefs, hopes, and expectations, and her emotions and moods. Practical intelligibility is teleologically and affectively determined.’ (Schatzki, 2001: 52). |

| ↑6 | Swidler continues: ‘But whether “practices” refer to individual habits or organizational routines, a focus on practices shifts attention away from what may or may not go on in actors’ consciousness — their ideas or value commitments — and toward the unconsciousness — their ideas or value commitments — and toward the unconscious or automatic activity embedded in taken-for-granted routines.’ (Swidler, 2001: 75). Obviously, in this position there is no important difference between habits, routines, and practice. |

| ↑7 | And when Swidler explains how ideas and values were replaced by practices in the sociology of culture, this change is — at least according to her take on practice — accompanied by an opening of practice to nearly anything, even to ideas. |

| ↑8 | ‘Thus the range of practices is wide: arts, sciences, games, politics in the Aristotelian sense, the making and sustaining of family life, all fall under the concept.’ (MacIntyre, 1994: 187). |

| ↑9 | Saussure’s theory was not entirely original. According to Noam Chomsky, Roger Bacon, Nicolas Beauzée, and John Stuart Mill, had all played with the idea of a some general principles prior to all languages, principles that ‘are the same as those that direct human reason in its intellectual operations’, according to Beauzée (Chomsky, 1985: 1). |

| ↑10 | ‘It is the social part of language, external to the individual, who by himself is powerless either to create it or to modify it. It exists only in virtue of a kind of contract agreed between the members of a community.’ (Saussure, 1983: 14). |

| ↑11 | Similar statements are found in the literature of both practice research and performance studies. As Richard Schechner says: ‘It is also true that only a few masters will be able to formulate in words the grammar of whatever performance genre they practice, be it kathakali, ballet, rock music, baseball, noh, or shamanism. Most performers will not be able to articulate precisely what they do, even if over time they get better and better at doing it.’ (Schechner, 2006: 233). |

| ↑12 | ‘A language as a structured system … is both a self-contained whole and a principle of classification.’ (Saussure, 1983: 10). |

| ↑13 | Tempting as it is to ascribe the highest degree of scientific value to the model that is most abstract and general, it is important to recognize that practice research will lose its raison d’être if it should be dissociated from the actual messiness of the practice, its performed activity. |

| ↑14 | ‘The term “performative” will be used in a variety of cognate ways and constructions … The name is derived, of course, from “perform”, the usual verb with the noun “action”: it indicates that the issuing of the utterance is the performing of an action – it is not normally thought of as just saying something.’ (Austin, 1962: 6—7). |

| ↑15 | Foucault states that the discourse (le discours) is a practice that has its own forms of sequence and succession (‘qui a ses formes propres d’enchaînement et de succession’) (Foucault, 1969: 221). Similar statements and observations can be found in the writings of de Certeau and Bourdieu. |

| ↑16 | See endnote 6. |

| ↑17 | It has, however, the inconvenience of suppressing both a far more complex chain of correspondence between the different links and the influence and participation of any other cultural, social or technological phenomenon. |

| ↑18 | Interestingly, this model also finds support in Saussure’s definition of ‘Speech’, where both the performative (and necessarily individual part) is in the following citation marked by (1), and what we have called ‘technique and skill conditions’ is marked by (2): ‘Speech, on the contrary, is an individual act of the will and the intelligence, in which one must distinguish: (1) the combinations through which the speaker uses the code provided by the language in order to express his own thought, and (2) the psycho-physical mechanism which enables him to externalise these combinations.’ (Saussure, 1983: 14). |