Celibidache Considered

DOI: 10.32063/1108

Table of Contents

Preliminary notes from the author.

N.B. The linked sound and video examples rigorously adhere to the fair use principles of international copyright law: (a) their use “transforms” the copyrighted material by using it for a different purpose than that of the original, (b) the brief excerpts quote no more of the copyrighted material than is necessary to illustrate the text, and (c) their use presents no financial detriment to the copyright owners.

Markand Thakar

Markand Thakar, Director of Conducting Programs International, is renowned world-wide as one of the major conducting pedagogues of the 21st century. Maestro Thakar, inspired and informed by his studies with Sergiu Celibidache, has appeared in performance with the New York Philharmonic, the National Symphony and some 40 orchestras around the world. He is author of On the Principles and Practice of Conducting, Looking for the Harp Quartet: An Investigation into Musical Beauty, and Counterpoint: Fundamentals of Music Making.

by Markand Thakar

Music & Practice, Volume 11

Reports & Commentaries

Sergiu Celibidache opened my ears and changed my life. As a 24-year-old Fulbright Fellow studying in Romania I was told I’d learn more from a single rehearsal of his than I had in my life to date. “Yeah, sure. Chela-who? Never heard of him.” Back in the US a respected mentor said: “if Celibidache is doing anything – GO!”[1] He was, and I went.

It was 1981, Celibidache’s conducting course with the Munich Philharmonic. He spoke my language.[2] I’d been studying the Eroica Symphony and couldn’t make sense of the last movement. Friends tried to reassure me, yes, it’s some variations, a little dance, a march, a chorale, what’s your problem? In Munich, Celibidache said, “The last movement of the Eroica symphony is … a SALAD!” Aaaaah, I’m home!

More importantly, I heard a different music, a magical experience of sound, sucking me in, moving me, exulting me. I left after two summers in Munich with a guiding understanding: that under certain conditions the magical moment of beauty that we have all experienced, that has drawn us all to music, can extend from the beginning of the first sound of a movement to the end of the last. Astonishing! And I came away, too, with a nascent understanding of some of those necessary conditions in sound. In 1984 I risked my graduate assistantship to attend his rehearsals and lectures at the Curtis Institute, along with the concerts in Philadelphia and New York. In 1989 I attended all four of the Munich Philharmonic concerts on the East coast, and my first book, Counterpoint: Fundamentals of Music Making (Yale University Press, 1990) is dedicated to him.[3]

His concerts could be mesmerizing. At the sound check of Bruckner’s Symphony no. 4 in a virtually empty Carnegie Hall I found myself in tears. His rehearsals and lectures were revelatory. The extensive recorded videos available online bespeak a music-making head and shoulders beyond the ordinary level of excellence … would we’d been in the hall to experience it!

Celibidache’s influence on my musical life has been and continues to be profound. His foundational insights inform my own further explorations, my music making as a conductor, and my passion for teaching. In this article I offer a glimpse into what he taught, some specifics of what he did on the podium that elevated his music-making beyond the customary high professional level, as well as some rare misses.

What he taught

Guiding Celibidache’s musical understanding was transcendence: the listener transcends consciousness of physical time and space, losing the everyday distinction between self and the sounds as external, and becoming in consciousness one with the sounds. It is an experience he equated with freedom – freedom from the world encompassing us, freedom from human suffering.

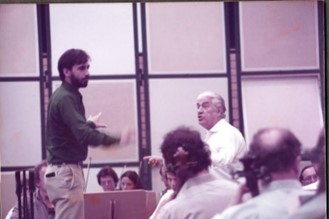

This transcendent experience can result when the listener absorbs the totality of a continuum of sounds in a single, undivided act of consciousness. The sounds – as suggested by the composer and brought to life by the performers – must allow it. To be absorbed in a single act of consciousness they must come to us as singular, as undivided, as a unity: “[The] biggest problem of the conductor is making an Einheit [unity], because man can only comprehend one thing at any given time” (Figure 1).

Performers create this possibility of oneness by reducing multiplicities. We play in tune to reduce a multiplicity of intonation systems; we play with good ensemble to reduce a multiplicity of metric systems. We balance the tones with a structure of volume that fuses them into a single entity. And – given a composition that allows it – we reduce a succession of tones to a single object. With inflections of volume and tempo we create a hierarchical structure of creating and releasing energy (impulse and resolution) such that the experience of every tone gives meaning to the tones already sounded and those as yet to come. We experience the totality in one extended now.

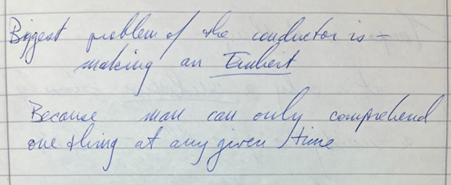

On a local level we use primarily volume to create groupings of energy and its release: louder creates energy; softer releases it.[4] Celibidache described the use of inflections of volume to create overarching unities out of successions of individual tones on a local level: “Tension is the force which lives within the phenomenon; intensity [volume] is the force with which we express it. We have no influence on the frequency (tension), but on the dynamics (intensity)” (Figure 2). And “We make a unity out of a group of notes via phrasing [volume inflections].”

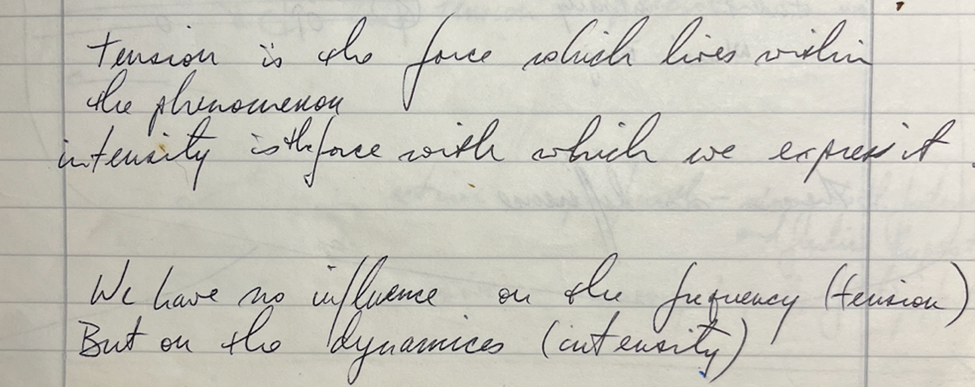

And (assuming a work that allows it) he described how we unfold a movement as a singular whole with an overarching creation and release of energy: by directing the tempo forward to the high point (climax) and allowing it to settle to the end (Figure 3).

Celibidache clearly understood as a musician – although to my knowledge never articulated – this essential corollary: that any grouping of tones can form a unity only if the energy created is resolved in equal measure, to the extent possible. This is true for any unity on any level, whether a grouping of tones, or a grouping of groupings, up to the whole movement at the highest level of the hierarchy.[5]

What he did

Celibidache’s understanding of structuring successions via volume inflections on a local level is what helped him get right in performance what so many have gotten and still get wrong.

Gabriel Fauré: Requiem, “In Paradisum” Download a reduced score

The link below is to a computerized realization of a reduction of the first 30 bars of the “In Paradisum” from Fauré’s Requiem. In particular note the deathly, amusical soprano line – exactly as Fauré gave it to us – completely lacking in inflection outside of the written crescendo and diminuendo of bars 24–27.

Video 1 Fauré: Requiem, “In Paradisum,” bars 1-30; computer realization

Consider how inflections of volume result in the unification of a succession of tones in Celibidache’s performance of the “In Paradisum” with the London Symphony Chorus and Orchestra. Starting in bar 3, the first four bars of the soprano line open up ever so slightly to the D of bar 5; they join with the next four bars into an eight-bar grouping that climaxes with the D of bar 8. The energy created is almost completely resolved by beat 3 of bar 10.

Video 2 “In Paradisum,” bars 1-10; London Symphony Chorus and Orchestra, Sergiu Celibidache

Next a two-bar grouping begins with the pickup to bar 11, climaxes with the downbeat of bar 12, and resolves within that bar. This grouping joins with the subsequent four-bar grouping into a six-bar grouping climaxing with the downbeat of bar 14. The climactic downbeat of bar 14 necessarily has more volume than that of bar 12; it creates sufficient energy to accommodate the two bar resolution of bars 15–16.

Video 3 “In Paradisum,” bars 11-16; Celibidache

Bars 17–18 form a grouping that climaxes on the downbeat of bar 18; it joins with the more insistent bars 19–20 into a four-bar grouping with a climax on bar 20. Finally bars 21–24 build energy via the indicated crescendo to the climactic f of bar 25; the energy created is released by the subsequent continuous diminuendo. And note the exquisite balance when the men join at bar 21.

Video 4 “In Paradisum,” bars 17-30; Celibidache

The magic comes from the creation of a single whole unit from these initial 30 bars: the increasingly strong climaxes at bars 14, 20, and 25 allow the first 24 bars to join into a single large-scale impulse, which is almost completely dissipated by the subsequent six-bar resolution. Have a listen, perhaps with eyes closed. You will hear a similar magical, unitary unfolding through the remainder of the work, with its global climax at bar 45. This is everything music can be, and it is rare.[6] Oh to have been in the hall!

Video 5 “In Paradisum,” complete; Celibidache

Beethoven: Symphony no. 3, i: Allegro con brio Download a reduced score (bars 1-45)

Another, more complex example, is the opening 45 bars of the first movement of Beethoven’s Eroica symphony. As expected in a sonata-form movement, the climax comes in the development (bar 279, beat 3). Thus the first 279 bars constitute one overarching gathering of energy, released in the subsequent 412 bars, and the first 45 bars participate in that global gathering of energy.

After the initial two explosive chords, the four-bar theme consists of a two-bar grouping climaxing with the G of bar 3, and a two-bar grouping climaxing with the Bb of bar 5. These two two-bar groupings join into a four-bar grouping in which the hopeful growth to a high Bb in bar 5 is thwarted by a deflating return to Eb in bar 6. The subsequent five-bar grouping climaxes with the sf Ab of bar 10; the limited resolution leaves energy that participates in the subsequent growth in bars 12–14. Overall, we have a climax on Bb in bar 5 growing to the sf Ab of bar 10, followed by an aborted grouping: a three-bar growth to a non-existent climax, the subito p of bar 15. The resultant hang-over of energy gives impetus for the next large-scale gathering of energy. In a performance by the Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Celibidache (1975) you will hear these fourteen bars unfolded as one in this optimal structure.

Video 6 Beethoven: Eroica Symphony, i, bars 3-14; Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra (1975), Celibidache

Contrast this with a performance by an excellent orchestra, the Frankfurt Radio Symphony, conducted by its music director Andrés Orozco-Estrada. Your initial impression may be shock at the speed: it is essentially at Beethoven’s metronome mark of dotted minim = 60.[7] At this breakneck speed the performance has a certain visceral excitement, but the speed prevents a transcendent, singular performance in multiple ways. Many of the faster tones are inaudible, and it lacks sufficient time to hear and create a dynamic structure that can result in an overarching unity. For example it is too fast for the musicians to make an immediate p at bar 15 from a forte at the end of bar 14. As a result, bars 12–14 make a full grouping climaxing with the downbeat of bar 14, and continuing with a diminuendo. This unfortunate resolution leaves no surplus of energy to fuel the next growth.

Video 7 Eroica Symphony, bars 3-14; Frankfurt Radio Symphony, Andrés Orozco-Estrada conductor

This next building of energy begins at bar 15 with the opening Eb triadic theme. But instead of dropping back down as in bars 6–7, it now begins a steady growth in pitch and in volume. In Celibidache’s performance you will hear the shape of the Eb, F Minor, and Ab triads opening up to the top and releasing with the fifth descent, as per the opening theme. You will also hear the growth in volume within the soprano line ascents to the Bb V 42 harmony of bars 29–30 and to the Eb6 harmony of bars 31–32. Take note of the singular overarching continuing growth from Eb (bar 15) to F (bar 19) to G–Ab (bars 20–21) to the six increasingly strong Bbs (bars 23, 27, 30, 32, 33, and 34) followed by the two-bar crescendo to the breakout tutti ff.

Video 8 Eroica, bars 15-37; Celibidache

By contrast, Señor Orozco loses steam by getting softer to the tops of the Eb and F minor statements of the opening ascending triads. And entire passage from bar 23 to bar 34 is deathly static, as aside from the sf accents the Frankfurters make zero volume differentiation.

Video 9 Eroica, bars 15-37; Orozco-Estrada

In Señor Orozco’s performance what should be a glorious heroic passage has the character of a waltz, due to the speed and downbeat accents. And then you will hear the grandeur in Celibidache’s performance, which maintains the structure of both the Eb major and C minor statements of the motive.

Video 10 Eroica, bars 37-34; Orozco-Estrada then Celibidache

Listen now to Celibidache’s performance of the first 44+ bars. Had we been in the hall we could have had an uninterrupted, singular, and transcendent experience.

Video 11 Eroica, bars 1-45; Celibidache

Beethoven: Symphony no. 9, ii: Molto vivace – Presto Download a reduced score

Celibidache also understood that unfolding an entire movement as a singularity involves tempo: tempo directed forward drives the energy toward a single global climax, tempo settling participates in its resolution (see Figure 3 above).

One of his favorite examples of a ubiquitous misunderstanding of tempo was the Scherzo of Beethoven’s ninth symphony. The movement begins Molto vivace, three crotchets to the bar, with a metronome indication of dotted minim = 116 – followed by stringendo to Presto, four crotchets to the bar, semibreve = 116. So clearly the Presto is faster than the Molto vivace. Unfortunately, the early editions notated the Presto not as semibreve = 116, but as minim = 116.[8] As this would result in nothing remotely like a Presto, the tradition has been – for some reason difficult to comprehend – to play the Presto at a leisurely Moderato. In Celibidache’s words, if it were a house, it would fall down … i.e. for the movement to be experienced as a whole the high point must come within the Presto, thus requiring a faster quality of motion, not a slower one.

Here are the opening few bars and then the stringendo to Presto from a performance conducted by Celibidache. The bar of the Molto vivace is equal in duration to that of the Presto, which logically is faster.

Video 12 Beethoven: Symphony no. 9, ii, bars 1-12 followed by bars 396-422; Munich Philharmonic (1989), Celibidache

Surprisingly – and disappointingly – numerous well-respected, brand name conductors completely misunderstand this essential tempo relationship. Beware the tumbling walls.[9]

Shostakovich: Symphony no. 5, iv. Allegro non troppo

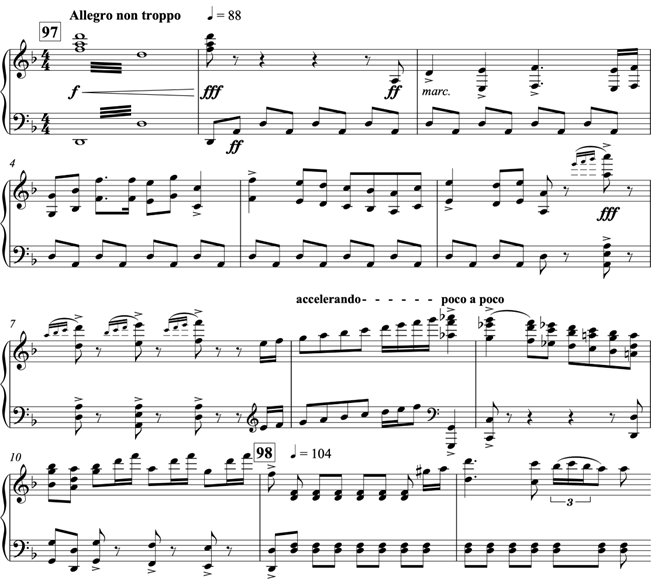

Two inexplicable, amusical performance traditions persist in the last movement of Shostakovich’s Symphony no 5. The first involves the tempo at the opening (Figure 4).

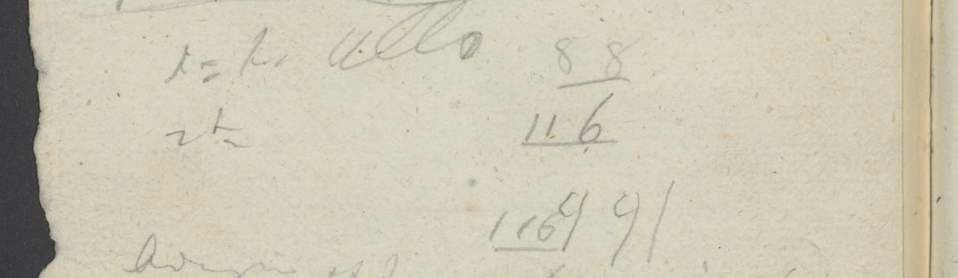

The finale of this monumental symphony builds energy to the climax with a gradual, barely perceptible increase of speed. The movement begins Allegro non troppo (fast, but not too much), he writes accelerando poco a poco (accelerate little by little), and if the Italian directions aren’t clear enough, he puts in metronomic guide markers indicating a gradually increasing speed: crotchet = 88 beats per minute to start, then 104, 108, 120, 126, 132, 144, and ultimately to the climactic 184.

Linked below is the opening of Celibidache’s performance with the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra from 1967. The image is an excerpt from Erich Leinsdorf’s score, on which he highlights in pencil both Shostakovich’s initial marking of crotchet = 88 and the subsequent crotchet = 104 at rehearsal number 98. Celibidache’s performance, Leinsdorf’s score.

Video 13 Shostakovich: Symphony no. 5, iv, bars 1-12; Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra (1967), Celibidache

Although the composer’s precise metronome mark is irrelevant to finding a good tempo,[10] this performance hews closely to Shostakovich’s indications of crotchet = 88 easing ahead to 104. If you can locate the full recording you will hear a building of speed – barely perceptible but nonetheless inexorable – to the terrifying climax.

By contrast, Leonard Bernstein’s famous 1959 Moscow performance with the New York Philharmonic reaches top speed virtually immediately, allowing zero possibility of building energy: another house falling down.

Video 14 Shostakovich: Symphony no. 5, iv, bars 1-12; New York Philharmonic (1959), Leonard Bernstein

But this is not a one-off. In fact it’s difficult to find a performance that does not get way too hot at rehearsal 98.[11]

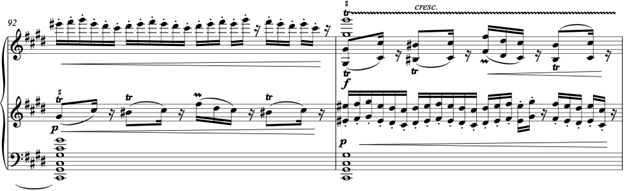

The second common mistake in performance involves an egregious misunderstanding of the shape of a local phrase.

The first violins begin an extended melody at rehearsal no. 119 (Figure 5). The initial 6-bar sub-grouping climaxes with the ascending leap to D on the downbeat of the fourth bar (first arrow), and releases that energy in the next three bars. That climactic moment is supported by the entrance of the second violins and violas, as well as with the harmonic climb from Db major to D minor. Another sub-grouping begins in bar 218 and gives an even stronger climax with the leap to A on bar 219 (second arrow), creating energy that is released over four bars. Celibidache makes the phrase beautifully.

Video 15 Shostakovich: Symphony no. 5, iv, bars 210-224; Celibidache

The common egregious error? Assuming that the pp indication for the inner voices at bar 215 is mistakenly missing in the first violin line, and thus that Shostakovich intended this bar to be suddenly softer. Of course the first violins are already pp, and a drop in volume at a climactic moment destroys the possibility of a unified experience of these tones … another house falling down.

Bernstein commits this offense too. Figure 6 is an excerpt of page 144 of his score showing his pencil marking of the phantom subito pp in the first-violin line at the 4th bar of rehearsal no. 119. You can hear the damage.

Video 16 Shostakovich: Symphony no. 5, iv, bars 210-224, Bernstein

Figure 6 Page 144 of Leonard Bernstein’s score of Shostakovich’s Symphony no. 5. Courtesy of NY Phil Shelby White & Leon Levy Digital Archives.

I have heard such a thing described as a negative climax: highlighting a tone with a sudden drop in volume, making it somehow special. Let me state emphatically that there is no such thing as a negative climax. If you are hiking to the top of a mountain and you fall into a hole, well that is a special moment to be sure, but you have not reached the height! Climax on a local level is created with increased levels of volume, not decreased.

Many conductors fall into this same hole.[12]

But (gasp!) he wasn’t perfect

It is easy to ascribe gospel status to the words and performances of a musician as brilliant, as superb, and as charismatic and supremely confident as was Sergiu Celibidache. But hero worship bespeaks a lack of comprehensive understanding. As it turns out, he was human.

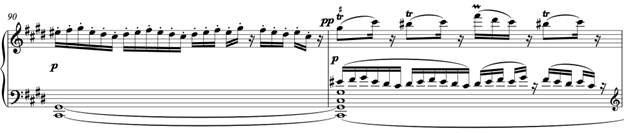

We heard in Celibidache’s sublime performance of the “In Paradisum” how the large-scale unity results from each grouping throughout the hierarchy creating energy and releasing it to the extent possible. And so a disappointment comes in multiple Celibidache performances of the passage from bar 90 to bar 111 of the Largo of the New World Symphony (Figure 7), where he fails to fully release the gathered energy.

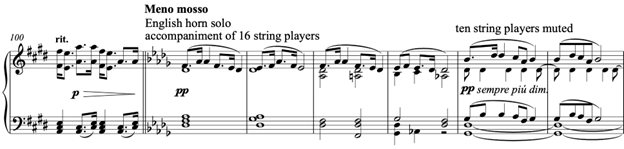

The energy builds steadily, adding volume and instruments, from the solo flute of bar 90 to the tutti ff of bar 96, climaxing with the ffz on beat 2 of bar 97 (the asterisk). Dvořák gives us crystal clear indications on the disintegration of that energy all the way through bar 110, by three different means. One is by reducing volume: ff – f – dim.– mp – dim.– p – dim. – pp – sempre piú dim. A second is by reducing the speed: rit. (bar 106) to Molto meno mosso (107) to stretching two bars into three, with added fermatas (107–109). And a third is by reducing instruments, from tutti full orchestra at the climax to trumpets and string sections (bar 106) to English horn and 16 muted string players (101) to ten muted string players (105) and finally to three (110). With the subtle beginning of a new gathering of energy in bar 111, we have a very clear guide to creating a single grouping: building energy (bars 90–97) and releasing it (97–110).

Unfortunately, conscientious principal string players commonly take the marking of “solo” in the part as synonymous with “project richly,” and thus the final, softest murmur is virtually always louder, thus preventing the full resolution of energy that Dvořák laid out so beautifully. But as in this typical Celibidache performance – linked below – the offending bump in volume was purposeful. Really, Maestro?

Video 17 Dvořák: Symphony no. 9, ii, bars 98-113; Munich Philharmonic (1991), Celibidache[13]

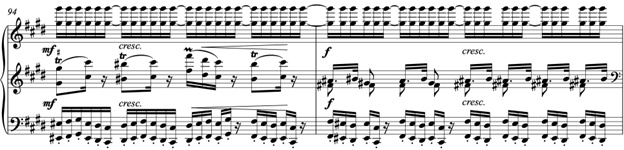

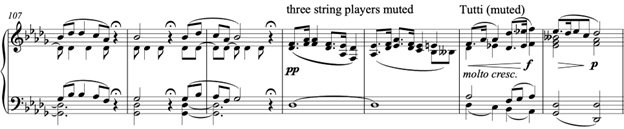

Another example is a passage in Tchaikovsky’s Symphony no. 5, movement 1 (Figure 8a). In a performance with the Munich Philharmonic in 1983 he tried to correct a traditional mistake with perhaps a worse one. Consider bars 198–199. The crotchet–quaver figure is the primary material, accompanied by the repeated percussive quavers. To make a unity of the crotchet–quaver figure, the crotchet must carry the weight. To make a single unit of the two-bar grouping, the first three crotchet–quaver figures must grow subtly in intensity to the fourth, with the energy resolving thereafter (Figure 8b, upper staff).[14]

However, the virtually universal performance convention is for the percussive accompaniment figure to grow all the way to the final quaver of bar 199 (Figure 8b bottom staff). An obvious problem is the jarring conflict with the upper-staff primary material.

Presumably in an effort to eliminate this conflict, Celibidache gives the same shape to both. But instead of conforming the accompaniment to the shape of the crotchet–quaver primary material and making a unified singular grouping (Figure 8c), he has the melodic material match the customary accompaniment growth to the final quaver (Figure 8d). The resultant burst of energy on the final quaver is unresolvable. Goodbye unity. The same is true of bars 202–203; in similar fashion the climaxes of bars 206 and 208 must come with the crotchets on the middle of the bar, and not the final quavers where Celibidache puts them. Say it ain’t so!

Video 18 Tchaikovsky Symphony no. 5, i, bars 198-213; Munich Philharmonic (1983), Celibidache

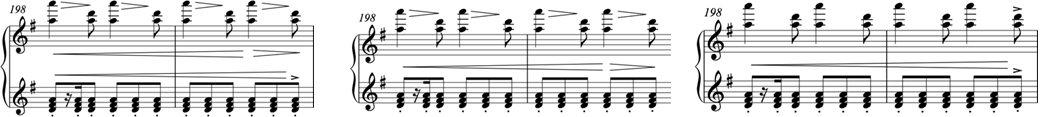

Another discordant note came from his inconsistency in applying a foundational element of his understanding: the consciousness must be absorbed fully and exclusively with the sounds.[15] Celibidache gave this wonderful example: “[There is] no relation between music and text – the dinner is served, the dinner is not served; the musical meaning is the same” (Figure 9). And as he understood that the focused consciousness is one, a consciousness directed to textual meaning is unavailable to experience the tones fully, and thus to an optimal, transcendent experience.

Yet in his rehearsal of Fauré’s Requiem with the London Symphony Chorus he frequently worked to match the music to the prosody of the text, to the detriment of the former. Perhaps the clearest instance comes in the Sanctus.

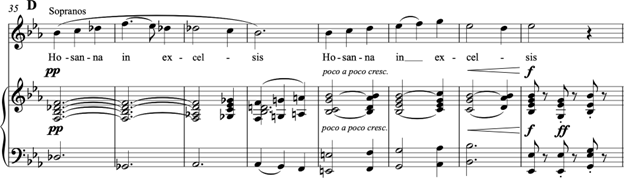

This 62-bar movement is built of two large-scale groupings: one climaxing in bar 20 at the height of a hairpin within p; and a second climaxing with an accented ff at bar 48. Bars 35–42 (Figure 10) participate in the energy gathering of that latter grouping, building toward the bar 48 global climax. Rehearsing the first four-bar phrase he asks the sopranos to sacrifice the prosody of the text for the musical strength on the syllable in; however in the subsequent four-bar phrase he asks sopranos to “let it fall,” so the sis of ex-cel-sis conforms to the prosody but directly contradicts Fauré’s crescendo to f.

Video 19 Fauré Requiem, “Sanctus”; bars 35-42; rehearsal, London Symphony Chorus, BBC documentary (1983)

While in the Dvořák Largo example above, the release of energy is interrupted with a bump in volume, in this movement the gathering of energy is interrupted by the dip in volume at bar 41. Sacrificing the prosody for the musical experience at bar 36 but not at bar 41? Difficult to understand. Nor was this a spur-of-the-moment idea in rehearsal, regretted later: it was so in the performance.

Video 20 “Sanctus”; bars 35-42; London Symphony Chorus and Orchestra (1982)

Finally, to address the elephant in the room of Celibidache’s perceived imperfections: tempo. I ascribe three reasons for criticism of his tempos as too slow, most of them misguided. (1) The tempos were not too slow; but they were slower than those to which people had become accustomed. There was more information in his performances, resulting from both greater volume inflections in the successions of tones, and beautiful balances of concurrently sounding tones, creating more perceivable overtones. More information needs more time. (2) The performance tempos were not too slow, but people reach this view from hearing recordings of his live performances, in different acoustics from the performance venue. Recordings eliminate a degree of the sonic information; less information in the same amount of time will likely result in a tempo experienced as too slow. I recall his celestial performance of the Tristan Prélude and Liebestod with the Curtis Institute Orchestra in Carnegie Hall, and later hearing a recording of it, to which my immediate reaction was “that’s too slow.” No it wasn’t. (3) He was human; some of his performances were too slow.

The examples of imperfections offered above are exceptions that prove the rule. Celibidache’s contributions as musician, thinker, and pedagogue were enormous, showing the possibility – and therefore the necessity – of seeking the optimal, transcendent, life-affirming experience from sound. This article represents a continuing reverence for his foundational insights, and his inspiration, that have made me a better musician. In Looking for the “Harp” Quartet[16] I refer to my contributions therein as standing on the shoulders of the proverbial giants Rameau and Schenker. I was remiss in not adding to that noble list the name of Sergiu Celibidache.

Endnotes

[1] Peter Perret, then music director of the Winston-Salem Symphony, whose lessons were a godsend for a young, thirsty-for-knowledge youth orchestra conductor in the musical wilderness of central North Carolina.

[2] Not literally, of course. He was fluent in Romanian, German, Italian, French, and I believe Spanish, but least comfortable in English. As a result, I found him nicest speaking English; otherwise most direct in German, most crude in Italian, and most sympathetic in Romanian with his countrymen.

[3] After the Munich Philharmonic concert in Worcester, Massachusetts, I told him about the book. His encouraging response: “You won’t know enough about counterpoint even after 300 lifetimes.”

[4] In fact resolution is a function of time; decreasing volume participates in the playing out of energy created.

[5] Note that the resolution comes with the qualifier “to the extent possible.” This is because, with the exception of a movement that ends with a dying out al niente, every grouping of tones must end with some degree of energy remaining. On lower levels of the hierarchy a grouping in which every scintilla of energy is dissipated would break the continuum; it is the left over energy that propels the impulse of the subsequent grouping. And it is composers’ recognition of the experience of a left-over wafting of dissipating energy following the forceful end of a movement that explains the common addition of a fermata over the final bar line, or over a final rest, or the addition of an extra bar of rest.

[6] By comparison, a sampling of recordings with brand-name conductors brings one limited performance after another, with beautiful sounding choirs, in tune, but without the subtleties of color and volume that allow for the optimal, magical, transcendent experience. Consider this performance conducted by Robert Shaw. The tones unfold note-by-individual-note, all at a similar volume, until the overwhelming f. And note the overbalancing of the sopranos by the men at bar 21. The result is a succession of individual events that cannot coalesce into a whole.

Or there is this pedestrian performance conducted by Richard Hickox. In contrast to Celibidache’s organ that participates in a delicate cushion of sound, this organ demands your attention from the get-go. The sopranos lack the intimate colour and subtle inflections of Celibidache’s sopranos, and it is overall just too loud. This is a small crystalline work, it can only take so much volume … the angels don’t sing that loud in paradise.

[7] Some assume that this should be conducted in one (one beat to the bar) because of the note value Beethoven gives for his metronome mark of dotted minim = 60. While it is difficult to imagine a situation in which that would not be too fast, Beethoven’s metronome only went up to 150; he did not have the option of a metronome mark at the value of the crotchet.

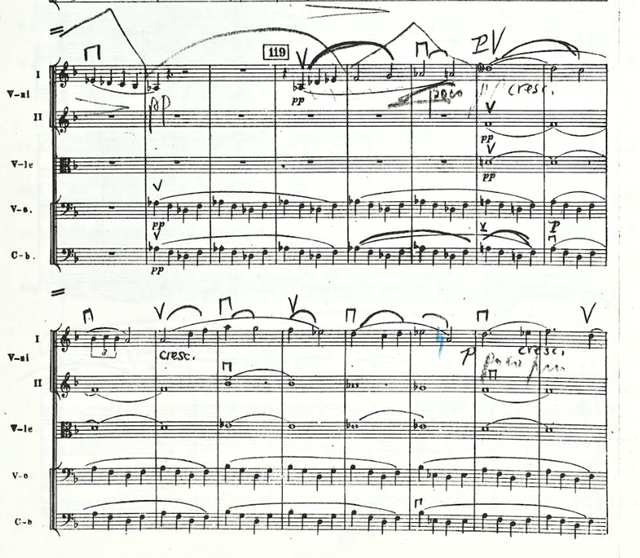

[8] In 1817 Beethoven sat down at a piano to notate metronome markings for his earlier works. At his side was his nephew Karl, armed with the metronome and a conversation book. Beethoven, virtually completely deaf by 1817, would bang out passages for Karl to write down the metronome number and the associated note value. In this brief excerpt of notes for Symphony 9 (Figure 11) we see the 1st movement marking of Allo. 88; followed by the 2nd movement: the opening Molto vivace given a metronome number of 116, and a second marking for the Presto also at 116. Unfortunately instead giving a semibreve for the Presto, Karl wrote 116 followed by two minims, evidently leading publishers to give a single minim as the associated note value.

Figure 11 Excerpt from the Conversation Book 122, folio 11; available from the Staatsbibliotheck zu Berlin

[9] Here is a Karajan performance … a superfast Molto vivace, proceeding to a leisurely so-called Presto. Paavo Järvi comes closer, but still the bar of his Presto is considerably slower than that of the Molto vivace. And after a speedy Molto vivace, Daniel Barenboim’s so-called Presto is the slowest yet.

[10] Consider the Eroica Symphony examples above, in which a metronome mark is clearly unhelpful in finding an effective tempo. For a comprehensive discussion of finding an ideal tempo see Markand Thakar, On the Principles and Practice of Conducting (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2016), 22-28.

Celibidache: “The day I learn something about music from a metronome is the day I will study with one.”

[11] Here is Mr. Solti with the Berlin Philharmonic, 1993; Señor Dudamel also with the Berlin Philharmonic, 2018; and Dudamel protégé Christian Vasquez with the Venezuelan National Youth Symphony, 2012. Simply a crime against music.

[12] Señor Vasquez does it, as does Paavo Järvi with the Orchestre de Paris, Valery Gergiev with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, and many others.

[13] Suggestion for listening: stop this clip at 1:50, hear in your mind the volume of the next entrance, then continue the clip. You will surely hear the entrance as too loud, and you will see Celibidache indicate the bump in volume.

[14] Emphasis occurring against the meter results in significantly more energy than emphasis occurring with it. For this reason climaxing the energy on the quaver in the crotchet-quaver figure would create too much impulse; it would also set up a new meter conflicting with that of the subsequent two bars. And within the two bars, if the energy were to climax before final crotchet it would die prematurely.

[15] See Figure 1: ‘[The] biggest problem of the conductor is making an Einheit [unity], because man can only comprehend one thing at any given time.’

[16] Markand Thakar, Looking for the “Harp” Quartet: An Investigation of Musical Beauty (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2011).