‘Declamatorischer Gesang’: Historical Singing Technique and Aesthetics in Vienna at the Time of Schubert

DOI: 10.32063/1103

Table of Contents

Bernhard Rainer

Born in Zell am See (Austria) Bernhard Rainer studied trombone in Graz, Vienna, London and Basel and musicology in Vienna. He is currently Assistant Professor of Historical Musicology at the University of Music and Performing Arts Graz (KUG) and teaches historical trombone at the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna (MDW).

by Bernhard Rainer

Music & Practice, Volume 11

Scientific

Although singing is of fundamental importance for the development of Western musical culture and the notion of what can and cannot be considered music is essentially derived from the phenomenon of singing, the reconstruction of historical singing styles and techniques has long been a stepchild of performance practice research.[1]

While research into instrumental performance practice can largely rely on surviving musical instruments and iconographic documents, historical vocal research lacks concrete artefacts as an object of investigation. Recordings of vocal music have only existed since the end of the nineteenth century and only allow limited conclusions to be drawn about earlier times. It is obvious that it is very difficult to reconstruct historical singing techniques from the only remaining evidence: the written sources. These circumstances may offer an explanation as to why the reconstruction of historical vocal aesthetics and techniques is still not at the level of contemporary instrumental historical performance practice, even years after this statement by Thomas Seedorf and Bernhard Richter.[2]

What follows is a case study of a kind – a first attempt to reconstruct a historical vocal aesthetic cultivated by singers who performed Schubert’s works during his lifetime.[3] To begin with, the fundamentals of vocal technique in the Schubert period will be explored in order to create an awareness of the differences between them and the modern standard. We will see that the position of the larynx, the use of the registers and vibrato, as well as the way in which the notes are attacked and connected, differed substantially from the modern practice. Finally, pronunciation – another area of singing technique that is essential to vocal aesthetics – will be discussed. In this context, a method of singing from Schubert’s environment is presented, which seems to transmit an important part of the style of singing that was a speciality of German-speaking performers in Vienna at the time: the so-called Declamatorischer Gesang (declamatory singing).

Previous attempts at reconstructing historic vocal techniques

Despite the obstacles, scholars have attempted to document a style of singing from the first third of the nineteenth century that was very different from the modern one. Mauro Uberti, in particular, has been publishing groundbreaking articles on historical vocal technique since the 1980s.[4] Marco Beghelli, in his dissertation and in several studies, has explicitly dealt with the theme of pedagogy and changes in vocal technique in the nineteenth century.[5] Richard Wistreich has also noted developments towards a new type of technique in the art of singing, which, in his opinion, began at the end of the eighteenth century.[6] Thomas Seedorf, Gregory W. Bloch and Corinna Herr have also dealt with aspects of singing in the nineteenth century.[7] In his monograph, Tenor: History of a Voice, John Potter repeatedly referred to decisive changes in singing technique around 1830, which should be seen in the context of the innovations first published by the famous pedagogue Manuel García (1805–1906).[8] Robert Toft agrees with Potter, as he notes in his book Bel Canto: A Performer’s Guide.[9] Toft has also written two monographs and an article on the history of singing in Italy and England before the decisive changes in the art of singing.[10] Dissertations by Sally Sanford and Sven Schwannberger also deal with an earlier time frame, while Barbara Gentili’s doctoral thesis and other publications cover the period from 1870 to 1925.[11]

Two recent artistic dissertations have highlighted interesting aspects of nineteenth-century vocal practice: Sarah Potter’s Changing Vocal Style and Technique in Britain during the Long Nineteenth Century (2014)[12] and Alexander Mayr’s Die voce faringea – Rekonstruktion einer vergessenen Kunst (2014).[13] Rebecca Grotjahn’s article Seelenvolle Maschine. Natur und Technik im Gesangsdiskurs was a groundbreaking contribution,[14] and Ingela Tagil recently published her thematically relevant work Coup de la Glotte and Voix Blanche: Two vanished techniques of the Garcia school (2020).[15]

From these publications, it is clear that until the second third of the nineteenth century, a style of singing prevailed which made far fewer modifications to the vocal tract and was therefore obviously closer to speech than modern singing techniques. In this context, one can assume that the vocal music of the time, which by its nature was closely linked to language, was created in accordance with this contemporary vocal aesthetic. This hypothesis may be particularly true of Franz Schubert’s lieder, for the well-known Schubert singer Johann Michael Vogl (1768–1840), who seems to have represented a particular style of singing, is said to have had a direct influence on the composer’s work.

Historical versus modern vocal aesthetics and technique

It can be assumed that historical vocal aesthetics differed in several respects from the singing method used in Western art music today. As already indicated, the essential features of modern vocal technique were developed in the 1830s of the nineteenth century – and thus only after Schubert’s death.[16] Decisive factors in the pedagogy of modern opera and concert singing are a fixed and slightly low-positioned larynx, as well as extensions in the lower throat, with which a balanced sound can be achieved over the entire vocal range.[17] Furthermore, this technique makes it possible to create resonances and so-called singer formants, through which a voice acting in a large opera house and accompanied by a full orchestra can be perceived effortlessly.[18] However, singing (or speaking) with a lowered larynx results in a darkening of the vocal sound, which has a lasting effect on the intelligibility of singers.[19] The vocal aesthetics before 1830, which presumably involved significantly fewer modifications of the vocal apparatus, may have been characterized by a greater proximity to speech. The declamation and intelligibility of vocal texts were decisively facilitated, and the tonal result can be described as less artificial than modern opera singing. For instance, the artificial effect of the singing technique with a low-positioned and fixed larynx is noted by Schmidt in 1843 in a very good comparison of ‘older’ and ‘newer’ singing techniques:

In ordinary singing, the larynx is raised gradually as one progresses from the lower to the higher notes in the scale. However, it is also possible to sing through the scale while the larynx remains in a fixed position at the bottom of the throat. In both cases the voice has a different sound in the higher notes: the timbre clair (voix blanche) in the first case; the timbre sombre (voix sombrée, voix couverte, voix en dedans) in the second case. The voix sombrée has something muffled (sourd), it gives the listener the impression that its formation is based on something forced, artificial.[20]

Furthermore, it can be postulated that the greater heterogeneity of the vocal sound afforded increased expressive possibilities, and that a flexible laryngeal position facilitated the execution of ornamentation and coloratura. This is supported by the observations of the eminent singer and singing teacher Julius Stockhausen (1826–1906), who commented on the singing technique of his teacher Manuel García (1805–1906). Although García was the first to describe the low laryngeal position in 1840, it apparently did not (yet) form the basis of his method:

But it is even more striking that he [García] did not establish his theory of the low laryngeal position as a law for tone formation in general, as the basis of vocal technique in general, even as a ‘conditio sine qua non’ for a musical, measured colouratura. Was the famous master afraid that the moderately low position of the larynx would make the throat less supple for Rossini’s firework-like runs? It almost seems that way to me … when I take a closer look at his and his father’s variations on the arias of the old and new Italian school.[21]

Flexible laryngeal position

Crucial evidence for this more natural use of the voice is the mention of a vertical movement of the larynx when singing as an ideal of the historical art of singing in scientific treatises on the voice and in singing methods. In the Vienna of Schubert’s time, people were well aware of these physiological processes, as can be seen from the following sources. The Viennese physician and voice researcher Georg Prochaska (1749–1820), for example, wrote in 1797:

From the lowest to the highest human voice, three octaves are generally counted; but the outermost notes are produced only with great effort, and usually uncleanly, except by very experienced singers … First, it is certain that the larynx is drawn upwards for higher notes and sinks downwards for lower notes. This raising and lowering of the larynx is about half an inch for one octave and consequently 11⁄2 inches for three octaves.[22]

The principle of the flexible larynx in singing is also evident in the singing school by Friedrich Starke (1774–1835), written in Vienna in 1819/1820:

The higher tone is produced when the larynx rises a little, the glottis narrows more, the glottis ligaments tighten more, and the airflow through the glottis is restricted; the opposite produces a lower tone.[23]

In another publication, of 1820, Prochaska confirmed the flexible effectiveness of the larynx in singing: ‘Firstly, it is quite visible that the larynx is raised in the higher voice and sinks in the lower voice’.[24] However, one of the most well-founded statements about the historical use of the voice by means of a flexible larynx was made by the Italian vocal physiologist Francesco Bennati (1798–1834):

The first phenomenon which presents itself here is that the soft palate rises on the low notes through the action of its elevator muscle … At the same time as the larynx is depressed, the soft palate turns backwards … Precisely the opposite phenomenon appears on the high notes … But instead of these muscles moving from front to back at the same time as the larynx is lowered, now, as the larynx rises, their movement is from back to front.[25]

Bennati is among the most credible witnesses to vocal aesthetics before the innovations that eventually led to modern singing technique, for he studied some of the most famous active singers of his time; several of these were also active in Vienna in the 1820s.[26]

Finally, Franz Eyrel informs us in his treatise on the art of singing that in the 1850s the use of the voice with an ascending and thus flexible larynx was still common in Vienna: ‘In order to give each tone the appropriate fullness, the pharynx narrows, the larynx rises and the uvula retracts, all to the extent that the tones become higher’.[27]

Register treatment

Another major difference between historical and modern vocal technique is in the treatment of register. As Alexander Mayr notes, there is a direct connection between the flexible laryngeal position and the use of falsetto in male voices. Since it was only with the technique of the lowered and fixed larynx that tenors in particular were able to reach the high register by expanding the chest voice – in the so-called modal register – the use of the falsetto, which is frowned upon today, was considered natural until the middle of the nineteenth century.[28] Special attention was paid to an imperceptible transition of the different sounding registers.[29] A successful combination of chest voice and falsetto was therefore the ideal, as the following description of the vocal qualities of the Bavarian tenor Franz Löhle (1792–1837), who performed at the Vienna Court Opera in 1820, demonstrates:

Among the foreign tenorists heard so far [ … ] Mr. Löhle stands out advantageously. From G to G, his voice actually comprises only one octave, but they are all sonorous, full chest notes that penetrate to the heart and fill the room of the house. The notes below G are weaker, the high A can only be reached with effort, so we do not count them, but we do notice that Mr. Löhle knows how to combine the falsetto notes with the chest voice very artfully and imperceptibly, which gives his performance grace and roundness.[30]

Almost equivalently, one of the most famous Viennese tenors of the time, Franz Wild (1791–1860; he sang Beethoven’s song ‘Adelaide’ accompanied by the composer in 1815), describes his own use of the high register in his biography:

My voice was of considerable range. It encompassed all notes with equal sonority and power from the low g to the high a-flat; indeed, on happy evenings I even took A with ease. I only learned to use the falsetto in 1825 when I was in Paris, where, under Rossini’s guidance, I acquired the ability to ‘go up’ in ornaments to the high C, even to the D … I finally achieved, through much and careful practice, that one did not notice the transition from the head voice to the chest voice.[31]

Significantly, sources on historical vocal aesthetics do not so much invoke the ideal of a uniform voice over the entire range, but rather demand a smooth transition of registers. August Swoboda’s Gesanglehre (Vienna, 1827) offers exercises for achieving this skill:

In order to connect the different voice registers mentioned in §13 smoothly and imperceptibly, one proceeds in the following manner. … If one wants to combine the middle voice with the head voice, the first note must be sung stronger and the second weaker, because the head notes are in any case more sonorous (actually more shrill). The latter must also be observed by men in the transition from the chest to the head voice.[32]

The importance of the register transition is also emphasized by Adolf Müller (1801–1886) in his Gesangschule published in Vienna in 1844, thus confirming the vocal aesthetics still common at that time:

These examples show that the last notes of the chest voice must be cultivated just as much as the first notes of the head voice, and that one is often forced to sing one and the same note in both registers. For this reason, it is also necessary to practise those related notes of the two registers equally and most carefully in order to be able to use them as required in each register.[33]

Vibrato

In contrast to modern opera singing, vibrato in historical vocal aesthetics was seen not as a component of sound production but as a means of enhancing expression, and it was used as an embellishment.[34] Viennese sources of the Schubert period do not usually discuss terms such as Bebung (quavering) or Tremolieren (tremolo) in relation to vocal music and thus seem to suggest that any vibrato-like phenomena that may have been practised did not play a major role. However, this situation changed dramatically in the 1840s. It is highly probable that the changes in vocal technique already described favoured the emergence of an audible, continuous vibrato, for from this time onwards it is mainly singers trained in Italy who are criticised for tremolo. As a survey of reviews of vocal performances in nineteenth-century Viennese newspapers revealed, negative evaluations regarding vibrato occurred disproportionately frequently in the period from 1840 to 1860, before continuous vibrato was apparently accepted as an aesthetic concept in the 1860s and no longer explicitly discussed after a final mention in 1868.[35]

Exemplary for this period is the following statement from 1845 about the voice of the court opera soloist Marie von Marra-Vollmer (1822–1878), who was trained by the Italian composer Gaetano Donizetti (1797–1848):

[T]he mania of quivering, this seemingly pathologically overstimulated vibrating of the tone, which in so many singers of the Italian school is carried to the point of lavish exuberance, we must of course wish to eliminate entirely where healthy, fresh cantilenas are concerned.[36]

Also significant in this regard is the explicit mention in 1855 of the avoidance of a continuous vibrato in the singing of the imperial chamber singer Luise Meyer-Dustmann (1831–1899), who was educated in Vienna at the Conservatorium der Musikfreunde: ‘she [avoids] quivering (tremolando) throughout, she holds the tone brought up to pitch calmly and firmly, an advantage that cannot be appreciated enough’.[37]

The following review of a court opera performance by the tenor Angelo Masini (1844–1924) in the newspaper Die Presse in 1877, in turn, seems to confirm the thesis of a changing sound ideal with regard to vibrato: ‘However, here the vibrato was reduced to a modest degree … The vibrato is, however, an artifice which, used in time, does not fail to have an effect’.[38]

Tone attack and connections

Between the vocal aesthetics of the Schubert period and modern concert and opera singing, there is a marked discrepancy in the treatment of tone onset and the connection of tones. In addition to the direct beginning of a phrase, since the end of the sixteenth century there is ample source evidence for the possibility of beginning a note below its nominal pitch.[39] Approximate tonal approaches and connections such as cercar della nota (search for the note) were used by singers as heightened means of expression until the second half of the nineteenth century, as the following review from 1855 seems to illustrate:

It is not conceivable that the human being is constantly in a state of passionate excitement; there must also be moments of calm. But these are never found in Miss Meyer’s singing. It is constantly emotion, which she tries to express by dragging and merging the notes together. It is true that she consistently avoids quivering (tremolando), she holds the tone brought to the pitch calmly and firmly, an advantage that cannot be appreciated enough; but the rarely immediate attack of the tones is just as much a mistake, which Miss Meyer will have to make an effort to avoid.[40]

Luise Meyer-Dustmann, already mentioned in connection with vibratoless singing, is criticized here for an overdramatized interpretation, which was very probably achieved through the creative devices of the cercar la nota (‘the rarely immediate attack of the tones’) and the portamento (the ‘dragging and merging the notes together’). Significantly, however, only the excessive use of these manners is criticized, but not their fundamental effectiveness in expressing the emotion of passion.[41]

Portamento can be described as another essential component of the art song of Schubert’s time.[42] The exact execution – especially the degree of blending between the notes – as well as the transfer of this manner from singing to musical instruments was the subject of lively discussion. A newspaper article in the Leipziger allgemeine musikalische Zeitung from 1814 is particularly instructive with regard to Viennese conditions:

The drawing through of notes, this manner, which is certainly pleasant in song, if it is used with great moderation, in the right place and with taste, and which was then rightly transferred from song to instrumental music, was so abused by violin players in a place where the art of music flourishes to a high degree (in Vienna) that very respectable men (such as Salieri) found it an atrocity and therefore, as far as their sphere of activity went, introduced a … formal prohibition against it, at least in orchestral playing, where it naturally belongs least of all … If one wanted to extend this to solo playing as well, then it would probably have been a little too strict again, and by eradicating this manner, according to the old proverb, the baby would be thrown out with the bathwater. Who can hear a good song without it?[43]

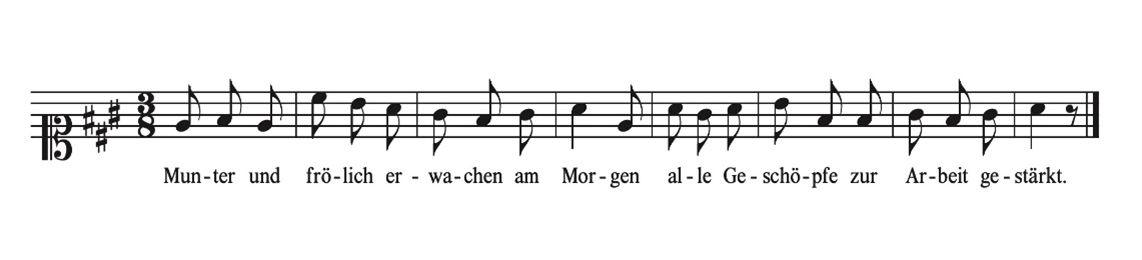

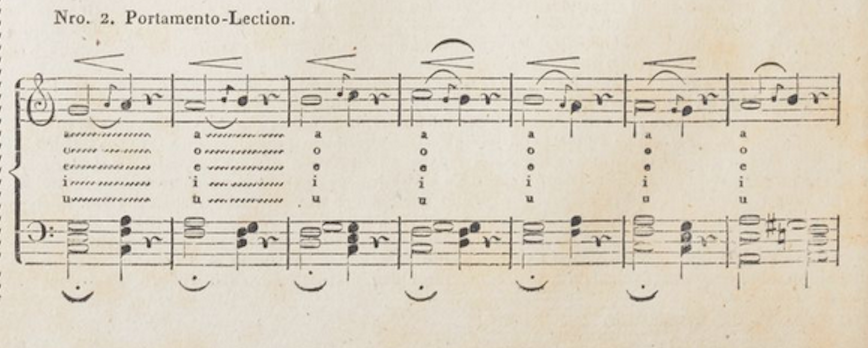

In the vocal tutors of Schubert’s time, portamento is described as elementary.[44] This was not, however, a glissando-like articulation of notes, which was universally rejected at the time,[45] but a manner of performance in which, in the sequence of two notes, the first was connected to the second by a slight anticipatory articulation of the latter (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Friedrich Starke, Kurzgefasste Gesang-Methode, appendix to: Wiener Pianoforte-Schule in III Abtheilungen (Vienna: the author, 1819/20), 2.

A true vocal glissando between two notes is mentioned positively in the sources only as a rare ornament. In this context, terms such as strascino, strascicando, strascinando, strascinar la voce, strisciature, cercar della nota, messa di voce crescente/decrescente, ziehen, schleifen and similar are used.[46]

Pronunciation – Declamatorischer Gesang

In general, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, a German, dramatic school of singing was propagated in Vienna in opposition to the prevailing Italian art of singing, and the soprano Anna Milder-Hauptmann (1785–1838) and baritone Johann Michael Vogl (1768–1840) were held to be the ideal representatives of this school.[47] Particular importance was attached to clear pronunciation and an artful delivery, and singers trained with special teachers of declamation such as Adolph Duprèe (1766–1833)[48] and Josepha Gottdank (1792–1857).[49]

This environment was decisive for Schubert’s German-language vocal music; in particular, Johann Michael Vogl’s interpretation of a so-called declamatory singing style had a direct impact on Schubert’s song compositions, as was stated by contemporaries:

Schubert … had the good fortune to win the affection of the court opera singer Vogl, already mentioned several times, this first declamatory singer of our time … Vogl guided his choice in relation to the poems, declamated the poems for him with his own captivating expression, which was already capable of leading the composer to the most suitable melody.[50]

and

… [Vogl] who, through the excellent declamatory performance of his songs, contributed a great deal to making them known and popular, and thus inspired Schubert himself to new creations in this field.[51]

As can be seen from a diary entry and from reports after his death, Vogl was planning to publish a tutor for this very declamatorischen und dramatischen Gesang (declamatory and dramatic singing), in which he apparently intended to discuss the ideal performance of Schubert’s songs.[52] The method of this prototypical representative of the German art of singing on dramatic performance has unfortunately not survived, but in the singing school of the Conservatorium der Musikfreunde in Vienna by Anton Rösner, at least the essence of declamatory singing seems to have been transmitted.[53] Rösner demonstrably had years of professional connections with Vogl and his location in the environment of the Viennese German singing school is obvious.[54] In addition, his acting activities – as early as 1799 he was presumably on stage with the legendary actor August Wilhelm Iffland (1759–1814) in Dessau – enabled him to treat pronunciation in song in a special way. In the relevant paragraphs in his tutor, he implies that clear declamation has priority over melodious, instrumental singing in any case. He makes this clear in particular in vivid text and musical examples on the pronunciation of consonants in singing:

The final consonants, especially the compound ones, are always given a short cut by the tongue, so that they do not merge with the following word, especially if it begins with a vowel, and thus become incomprehensible to the listener: e.g.:

Munter und fröhlich erwachen am Morgen, alle Geschöpfe zur Arbeit gestärkt.

And not: Munterund fröhlicher wachenam Orgen, alle Geschöpfe zurarbeit gestärgd [see Figure 2].

… in particular, no consonant may be swallowed or pronounced indistinctly, but it must be struck audibly with the tongue, creating a small paragraph: e.g.: Wer begreift das Werk der Allmacht, wer die Langmuth unsers Schöpfers? And not: Wea be Greif das Weag dea Allmachd, wea die Langmuhd unseas Schöpfeas? … If the consonant is between two vowels in a word, it is drawn to the next syllable according to the rule: e.g.: wa_chen, and not wach_en.

If, however, in compound words two consonants stand between two vowels … the consonants must not be drawn to the following syllable, e.g.: wach_auf, and not wa_chauf.[55]

In terms of vocal technique, this speech-focused, non-bound performance is achieved through a ‘short cut by the tongue’ and clear separation of words. The consequence of Rösner’s instructions is that a continuous legato is not possible. The Leitfaden einer Gesanglehre of the Vienna Conservatory is thus obviously in complete congruence with Vogl’s declamatory and dramatic singing, which set itself apart from the legato style and more lyrical singing ideals of the time.[56] Rösner is particularly explicit again at the end of the paragraph on declamation:

In general, in order to pronounce and be understood quite clearly, all notes with one, two or even three consonants should always be sung somewhat shorter than the actual value of the note.[57]

Although Italian and Latin vocal works were performed on an equal footing with German in the concerts of the Conservatorium der Musikfreunde, and other Viennese singing schools of the time very well contain instructions for the pronunciation of foreign languages, Rösner’s Leitfaden einer Gesanglehre only treats German.[58] His singing school is to be named as the most important witness of German declamatory and dramatic singing and proves that this was also common practice in Vienna beyond Johann Michael Vogl’s time in the first half of the nineteenth century – Rösner’s method was, after all, published again by his successor Laurenz Weiss in 1842.[59] Interactions of this vocal aesthetic, which is based on historical, speech-like vocal technique and, beyond that, on declamation, with Schubert’s song oeuvre are obvious and are supported by sources from his environment.

Later nineteenth-century declamation

Whether the Viennese declamatory singing school, presumably influenced by Vogl, was a locally limited circle of interpreters cannot be decided at present. From the middle of the nineteenth century onwards, opposing positions regarding speech-bound, separate declamation or legato performance can be observed in German-language vocal pedagogical writings. Friedrich Schmitt (1854), Ferdinand Sieber (1856) and Franz Hauser (1866), for example, all advocate legato performance in German singing in their tutors.[60] In contrast, the Mannheim court singer Oskar Guttmann in 1861 demands similar declamatory rules regarding the text as Rösner:

A big mistake is to drag the last consonant of a word over to the beginning vowel of the next word. This must not be done … For example, instead of: Graf Eberhard either Gra Feberhard, or … Gra Weberhard. This is only a vagueness; but we hear a completely different sense in the following: ‘seit ich’ [since I] we hear almost everywhere as ‘sei dich’ [be you]; also: gute Nabend instead of guten Abend; further: um un dum instead of: um und um, and wa sist instead of : was ist, etc.[61]

Another advocate of declamatory recitation in the second half of the nineteenth century was Thuiskon Hauptner (1821–1899), who postulated in an undated method that a final consonant should never be drawn into the following word: ‘One should sing: Im-Opfer and not Im-mopfer [one should sing] Macht – alles [and not] Mach-talles [ … ]’.[62]

Gustav Engel took a middle position in this controversial discourse in 1874. He believed that in questionable passages, musical expression should decide over continuous legato or declamatory performance.[63] In the last third of the nineteenth century, however, the legato performance, which is still authoritative in modern opera singing, may have finally established itself in German vocal music, as can be read in Julius Stockhausen’s work:

If one wants to sing a solemn piece with text, the main condition is that each note and each syllable be given its full value. Breaking off a note, dwelling too long on a consonant, doubling it where it should be used simply, completely destroys the effect of the bound performance.[64]

Résumé

In the contemporary concert setting, Schubert’s vocal music is performed almost exclusively by singers who have acquired modern classical vocal technique. However, as various studies have already argued, vocal performance practice in the nineteenth century was fundamentally different from contemporary practice. In contrast to modern vocal technique, the historical vocal aesthetic was probably characterized by far fewer muscular contractions in the production of the voice. Until the mid-nineteenth century, it is possible that singers may have cultivated a vocal technique that can be described as closer to speaking than is customary today. The interactions of this vocal aesthetic, founded upon a historical, speech-like vocal technique and extending beyond that to declamation, with Schubert’s song oeuvre are apparent, and supported by sources from his environment. It thus appears appropriate to have undertaken a case study with the objective of reconstructing the historical vocal aesthetic cultivated by singers who performed Schubert’s works during his lifetime.

In contrast to the fixed and lowered larynx position that is a feature of modern classical singing technique, the Viennese sources of the first half of the nineteenth century seem to testify that a flexible laryngeal position was used by professional singers, as in speech, and fewer modifications of the lower pharynx were attested. This may be taken to have resulted in a more natural-sounding outcome than is perceived today. Furthermore, different vocal registers were tolerated in historical singing to a greater extent than today, which gave the singers of Schubert’s time a far more colourful means of expression. Reviews from nineteenth century Viennese newspapers also suggest that continuous vibrato – an integrative element of sound in modern vocal technique – was not developed until the second third of the century, roughly coinciding with significant changes in vocal technique observed from 1830 onwards. In contrast, today frowned upon approximative tonal beginnings and connections, such as the cercar della nota and the portamento, were frequently used in historical vocal aesthetics as expressive performance devices.

A particularly noteworthy finding of the present study is that at least essential elements of the Schubert singer Johann Michael Vogl’s so-called declamatory singing are likely to have been preserved in the Leitfaden einer Gesanglehre by the Viennese conservatory professor Anton Rösner. In the relevant paragraphs in his tutor, Rösner implies that clear declamation has priority over melodious, instrumental singing in any case. A speech-focused, non-bound performance is achieved through the clear separation of words, which, as a consequence, makes a continuous legato as usually executed in modern singing impossible.

This study offers a first starting point for the reconstruction of historical Schubert singing. It also has the potential to open up a new perspective on the composer’s vocal works due to the apparent correspondence between the vocal aesthetics of contemporary performers and the creative process.

Endnotes

[1] Thomas Seedorf and Bernhard Richter, ‘Befragung stummer Zeugen – gesangshistorische Dokumente im deutenden Dialog zwischen Musikwissenschaft und moderner Gesangsphysiologie’, in Basler Jahrbuch für historische Musikpraxis 26 (2002), 173–186, at 173: ‘Obwohl das Singen für die Entwicklung der abendländischen Musikkultur von grundlegender Bedeutung ist und die Vorstellung von dem, was als Musik gelten könne und was nicht, wesentlich vom Phänomen des Gesangs abgeleitet wird, war die Rekonstruktion historischer Gesangsstile und -techniken lange Zeit ein Stiefkind aufführungspraktischer Forschung’. All translations are my own.

[2] An empirical PhD project by Helena Daffern in 2008, for example, showed that singers from the so-called early music scene use the same technical singing methods as contemporary opera singers. See Helena Daffern, Distinguishing Characteristics of Vocal Techniques in the Specialist Performance of Early Music (PhD diss., University of York, 2008), 2 (abstract): ‘Although classified as having a characteristically distinct sound from opera singers, early music singers were found to utilise methods of vocal production strongly representative of a modern operatic technique. Differences that were identified between early music and opera singers seem to represent the individual vocal backgrounds of the singers rather than any scholarly revival of historical vocal techniques. The training of the singers and particularly their choral background seemed to be a major determining factor of the singers’ speciality. In spite of a scholarly interest in historical vocal techniques infiltrating performance institutions to various extents in recent years, the central objective of the singers appears to remain the need to conform to conventional aesthetic of a “classical” voice’. See also Richard Wistreich and John Potter, ‘Singing Early Music: A Conversation’, Early Music, 41/1 (2013), 22–26.

[3] A comprehensive list of the singers active during Schubert’s lifetime can be found in David Montgomery, Franz Schubert’s Music in Performance (Hillsdale: Pendragon Press, 2003), 17–18.

[4] Mauro Uberti, ‘Vocal Techniques in Italy in the Second Half Of the 16th Century’, Early Music 9/4 (1981), 486–95; Uberti, ‘Caratteri della tecnica vocale in Italia dalla lettera sul canto di Camillo Maffei al trattato di Manuel Garcia’, in La situazione attuale degli studi e della ricerca sulla tecnica vocale e sulla didattica della vocalità con particolare riferimento al canto corale: 15. Convegno europeo sul canto corale promosso e organizzato dall’Associazione corale goriziana C.A. Seghizzi: Gorizia, Sala convegni (Espomego), agosto 1984: atti e documentazioni / a cura di Italo Montiglio (Gorizia: Grafica goriziana, 1987), 23–53; Uberti, ‘Sembrava uno sbadiglio, era una nuova tecnica di canto’, La Stampa, 29 January 86, available at www.maurouberti.it/sbadiglio/sbadiglio.html.

[5] Marco Beghelli, I trattati di canto italiani dell’Ottocento. Bibliografia, caratteri generali, prassi esecutiva, lessico (PhD diss., Università degli Studi, Bologna, 1995), Beghelli, ‘Il ‘Do di petto’: Dissacrazione di un mito’, Il Saggiatore musicale, 3/1 (1996), 105–49, Beghelli, ‘Singing Bodies: The Visual Metamorphosis of Rossini’s Arnold from “canto di grazia” to “Belting”’, in Rossini after Rossini: Musical and Social Legacy, ed. Arnold Jacobshagen (Turnhout: Brepols, 2020), 123–51.

[6] Richard Wistreich, ‘Reconstructing Pre-Romantic Singing Technique’, in The Cambridge Companion to Singing, ed. John Potter (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 178–91, at 178. Wistreich claims that the technique of a lowered laryngeal position in singing was developed at the end of the eighteenth century, but he does not cite any sources. He may be referring to sources from the late eighteenth century which report singers who incorrectly extended the chest voice upwards, and which Marco Beghelli cites in his dissertation. See Beghelli, I trattati di canto italiani, 224. However, these accounts probably refer to a technique known today as belting and not to revolutionary singing with the larynx in a low position. For singing with a lowered larynx position, see below. See also Richard Wistreich, ‘Practising and teaching Historically Informed Singing – Who Cares?’, in Basler Jahrbuch für historische Musikpraxis, 26 (2002), 17–29, at 28.

[7] Thomas Seedorf, ‘Oper und Vokalmusik’, Neues Handbuch der Musikwissenschaft, 11 (1992), 321–41; Seedorf, ‘Altitalienische Gesangsmethode und deutsche Gesangspädagogik’, Singen und Lehren zwischen Tradition und Moderne: XXII. Jahreskongress des Bundesverbandes Deutscher Gesangspädagogen, ed. Bundesverband Deutscher Gesangspädagogen (Detmold: BDG, 2011), 130–39; Seedorf, ‘Das Falsett der Tenöre: Zu Klangästhetik und Gesangstechnik von Tenören des frühen 19. Jahrhunderts’, in Der Countertenor: Die männliche Falsettstimme vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart, ed. Corinna Herr, Arnold Jacobshagen, Kai Wessel (Mainz: Schott, 2012), 155–66; Seedorf, ‘Vom Tenorhelden zum Heldentenor: Richard Wagner und das Ideal eines neuen Sängertypus’, in Musik und kulturelle Identität, ed. Detlef Altenburg and Rainer Bayreuther (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2012), 1:463–72; Seedorf, ‘Singen: Historische Aspekte’, in MGG Online, www.mgg-online.com/mgg/stable/11802 (30 July 2021); Seedorf and Richter, ‘Befragung stummer Zeugen’, in Basler Jahrbuch für historische Musikpraxis 26 (2002), 173–186, Gregory W. Bloch, ‘The Pathological Voice of Gilbert-Lois Duprez’, Cambridge Opera Journal, 19/1 (2007), 11–31; Corinna Herr, ‘Zur Pariser Tenor-Situation um die Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts: Von Faust zu den Pêcheurs de perles’, in Der Tenor: Mythos – Geschichte – Gegenwart, ed. Corinna Herr, Arnold Jacobshagen, and Thomas Seedorf (Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2017), 145–83.

[8] John Potter, Tenor: History of a Voice (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 46, 52, 59, 79. See also Potter, ‘Vocal Performance in the “Long Eighteenth Century”’, in The Cambridge History of Musical Performance, ed. Colin Lawson and Robin Stowel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 506–26.

[9] Robert Toft, Bel Canto: A Performer‘s Guide (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 19.

[10] Robert Toft, ‘Action and Singing in Late 18th and Early 19th Century England’, Performance Practice Review, 9/2 (1996), 146–62, Toft, Heart to Heart: Expressive Singing in England 1780–1830 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), Toft, With Passionate Voice: Re-Creative Singing in 16th Century England and Italy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

[11] Sally Allis Sanford, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Vocal Style and Technique (DMA diss., Stanford University, 1979), Sven Schwannberger, Studio et Amore: Die Gesangskunst des 17. Jahrunderts in italienischen und deutschen Quellen (PhD diss., Hochschule für Musik Detmold, 2019), Barbara Gentili, The Invention of the ‘Modern’ Voice: Changing Aesthetics of Vocal Registration in Italian Opera Singing 1870–1925 (PhD diss., Royal College of Music, London, 2018), Gentili, ‘The Birth of “Modern” Vocalism: The Paradigmatic Case of Enrico Caruso’, Journal of the Royal Musical Association, 146/2 (2021), 425–53, Gentili, ‘The Changing Aesthetics of Vocal Registration in the Age of Versimo’, Music and Letters, 102 (2021), 54–79.

[12] Sarah Potter, Changing Vocal Style and Technique in Britain during the Long Nineteenth Century (PhD diss., The University of Leeds, 2014).

[13] Alexander Mayr, Die ‘voce faringea’ – Rekonstruktion einer vergessenen Kunst (Artistic diss., University of Music and Performing Arts, Graz, 2014).

[14] Rebecca Grotjahn, ‘Seelenvolle Maschine: Natur und Technik im Gesangsdiskurs’, in Naturalezza | Simplicité – Natürlichkeit im Musiktheater, ed. Vera Grund, Claire Genewein, and Hans Georg Nicklaus (Bielefeld: Transcript, 2019), 81–107.

[15] Ingela Tagil, ‘Coup de la Glotte and Voix Blanche: Two Vanished Techniques of the Garcia School’, Music and Practice, 7 (2020), www.musicandpractice.org/volume-7/.

[16] John Potter and Robert Toft also pointed to this point of origin: Potter, Tenor, 46, 52, 59, 79; Toft, Bel Canto, 19.

[17] On modern voice research and vocal pedagogy see Johan Sundberg, The Science of the Singing Voice (Dekalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1987). Vocal physiological differences between historical use of the voice and modern singing technique were vividly illustrated by Seedorf and Richter, ‘Befragung stummer Zeugen’, 175–86.

[18] The so-called singer’s formant causes an increase in the sound transmission capacity of tenors in the range of 3 kHz by 20 dB. Sundberg, The Science of the Singing Voice, 143.

[19] Male singers with modern vocal technique have been shown to have a vowel migration from [i] to [y], [a] to [o], and [e] to [œ], while speaking with lowered larynx the sound of all vowels shifts towards [œ]. See Sundberg, The Science of the Singing Voice, 138–39 and 142.

[20] Carl Christian Schmidt, ‘Vom Singen’, in Encyklopädie der gesammten Medicin (Leipzig, 1843), 313: ‘Beim gewöhnlichen Singen findet sich in gleichem Verhältnisse, als man in der Tonleiter von tiefen zu den höheren Tönen fortschreitet, ein allmäliges Erheben des Kehlkopfes statt. Es ist indessen auch möglich, dass die Tonleiter durchgesungen wird, während der Kehlkopf in einer festen Stellung unten am Halse verharrt. In beiden Fällen hat die Stimme in den höheren Tönen einen verschiedenen Klang: den Timbre clair (Voix blanche) im ersten Falle; den Timbre sombre (Voix sombrée, Voix couverte, Voix en dedans) im zweiten Falle. Die Voix sombrée hat etwas Gedämpftes (sourd), sie macht auf den Zuhörer den Eindruck, dass ihrer Bildung etwas Erzwungenes, Künstliches zu Grunde liegt’.

[21] Julius Stockhausen, Gesangsmethode (Leipzig: C.F. Peters, 1884), 20: ‘Noch auffallender ist es aber, dass er [García] seine Theorie der tiefen Kehlkopfstellung nicht als Gesetz für die Tonbildung überhaupt, als Grundlage der Stimmbandtechnik im Allgemeinen, auch als ‚conditio sine qua non’ für eine musikalische, gemessene Coloratur aufstellte. Fürchtete der berühmte Meister, durch die mässig tiefe Kehlkopfstellung die Kehlen minder geschmeidig für die Rossini’schen feuerwerkartigen Läufe zu machen? Fast will es mir so scheinen … wenn ich seine und seines Vaters Varianten zu den Arien der alten und neuen italienischen Schule näher betrachte’. See also Manuel García, École de Garcia: Traité complet de l’art du chant par Manuel Garcia fils (Mainz/Paris, 1840).

[22] Georg Prochaska, Lehrsätze aus der Physiologie des Menschen (Vienna: Christian Friedrich Wapplar, 1797), 42–43: ‘Von der tiefesten bis zur höchsten menschlichen Stimme zählet man gewöhnlich drey Oktaven; doch werden davon die äussersten Töne nur mit großer Anstrengung und zwar meistens unrein, ausser von sehr geübten Sängern, herausgebracht. … Erstens ist gewiss, daß der Kehlkopf bey feineren Tönen in die Höhe gezogen werde, und bey tiefen Tönen niedersinke. Dieses Steigen und Fallen des Kehlkopfs beträgt bey einer Oktave ungefähr einen halben Zoll, folglich bey drey Oktaven 11⁄2 Zoll’.

[23] Friedrich Starke, Kurzgefasste Gesang-Methode, appendix to Wiener Pianoforte-Schule in III Abtheilungen, (Vienna: the author, 1819/20), 4: ‘Der höhere Ton wird hervorgebracht, indem der Kehlkopf sich etwas erhebt, die Stimmritze sich mehr verengert, die Stimmritzebänder sich mehr spannen, und der Luftstrom durch die Stimmritze beschleiniget wird; das Gegentheil bewirkt einen tiefen Ton’.

[24] Georg Prochaska, Physiologie oder Lehre von der Natur des Menschen (Vienna: Karl Ferdinand Beck, 1820), 308–9: ‘Erstens ist es ganz sichtbar, dass der Kehlkopf bey höherer Stimme gehoben wird, und bei tieferer niedersinket’.

[25] Francesco Bennati, Die physiologischen und pathologischen Verhältnisse der menschlichen Stimme [ … ] Nach dem Französischen frei bearbeitet (Illmenau: Bernh. Friedr. Voigt, 1833), 10–11: ‘Die erste Erscheinung welche sich hier darbietet ist, daß der weiche Gaumen sich bei den tiefen Tönen durch die Thätigkeit seines Hebemuskels erhebt … Gleichzeitig mit der Niederdrückung des Kehlkopfes wendet sich hierbei das Gaumensegel nach hinten … Gerade die entgegengesetzte Erscheinung zeigt sich bei den hohen Tönen. … Anstatt daß aber dort diese Muskeln gleichzeitig mit der Senkung des Kehlkopfes sich von vorn nach hinten bewegen, geht jetzt, indem der Larynx sich erhebt, ihre Bewegung von hinten nach vorn’.

[26] Bennati mentions the following singers who were active in Vienna: Giovanni David (1790–1868), Giovanni Battista Rubini (1795–1854), Luigi Lablache (1794–1858), and Henriette Sontag (1806–1854). Sontag created the title role in Carl Maria von Weber’s Euryanthe at the Kärtnertortheater in Vienna in 1823 and sang the soprano part in the premiere of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in 1824.

[27] Franz Eyrel, Die Stimmfähigkeit des Menschen und ihre Ausbildung für Kunst und Leben (Vienna: Mechitaristen-Buchdruckerei, 1854), 33: ‘Um jedem Tone die angemessene Fülle zu geben, verengert sich der Schlund, erhebt sich der Kehlkopf, und zieht sich das Zäpfchen zurück, und zwar alles in dem Masse als die Töne höher werden’.

[28] Mayr, Die voce faringea, 26–27.

[29] See also Thomas Seedorf, ‘Das Falsett der Tenöre: Zu Klangästhetik und Gesangstechnik von Tenören des frühen 19. Jahrhunderts’, in Der Countertenor. Die männliche Falsettstimme vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart, ed. Corinna Herr, Arnold Jacobshagen, Kai Wessel (Mainz: Schoot, 2012), 155–66.

[30] Anon., ‘Wiener-Schaubühnen’, Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung mit besonderer Rücksicht auf den österreichischen Kaiserstaat 79 (30 September 1820), 627–28: ‘Unter den bisher gehörten fremden Tenoristen … zeichnet sich Herr Löhle vorteilhaft aus. Seine Stimme umfasst von G bis G eigentlich nur eine Octave, doch sind es alle klangreiche, volle Brusttöne, die zum Herzen dringen und den Raum des Hauses erfüllen. Die Töne unter G sind schwächer, das hohe A nur durch Anstrengung erreichbar, daher wir sie nicht zählen, bemerken aber dafür, dass Herr Löhle die Falsettöne mit der Bruststimme sehr kunstreich und unmerklich zu verbinden weiss, was seinem Vortrage Grazie und Ründung verleiht’.

[31] Franz Wild, ‘Autobiographie VII. (Schluß) – Mein Jubiläum. Geschichte meiner Stimme’, in Recensionen und Mittheilungen über Theater und Musik 9 (29 February 1860), 124: ‘Meine Stimme war von bedeutendem Umfang. Sie umfaßte alle Töne in gleicher Klangfülle und Kraft vom tiefen g bis zum hohen as; ja ich nahm an glücklichen Abenden auch A mit Leichtigkeit. Das Falsett lernte ich erst im Jahre 1825 bei meiner Anwesenheit in Paris gebrauchen, wo ich mir unter der Anleitung Rossini’s die Fähigkeit erwarb, bei Verzierungen bis in das hohe c, ja selbst bis ins d “hinaufzugehen” … ich brachte es durch viele und vorsichtige Uebung endlich dahin, daß man den Uebergang aus der Kopf- in die Bruststimme nicht merkte’. See also Seedorf, ‘Das Falsett der Tenöre’, 163–64.

[32] August Swoboda, Gesanglehre (Vienna: Anton v. Haykul, 1827), 11: ‘Um die verschiedenen, §. 13. Angeführten Stimmregister fließend und unmerklich aneinander zu schließen, verfahre man auf folgende Art. … Will man die Mittelstimme mit der Kopfstimme verbinden, so muß der erste Ton stärker, und der zweyte schwächer gesungen werden, weil die Kopftöne ohnehin klingender (eigentlich gellender) sind. Dieß letztere müssen auch Männer beym Übergang von der Brust- zur Kopfstimme beobachten’.

[33] Adolf Müller, Neue vollständige Gesangschule (Vienna: Tobias Haslinger’s Witwe und Sohn, 1844), 27: ‘Aus diesen Beispielen ergiebt sich, dass die letzten Töne der Bruststimme eben so cultivirt werden müssen als die ersten der Kopfstimme, und dass man oft genöthigt ist einen und denselben Ton in beiden Tonregistern vorzutragen. Deshalb ist es auch erforderlich jene verwandten Töne der beiden Register gleichmässig und auf das Sorgfältigste zu üben, um sie nach Erforderniss in jeder Stimmlage anwenden zu können’.

[34] On vibrato as ornamentation, see Greta Moens-Haenen, Das Vibrato in der Musik des Barock, 3rd ed. (Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, 2021); Clive Brown, Classical and Romantic Performance Practice 1750–1900 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 517–57; Klaus Mieling, ‘Zur Rolle des Gesangsvibratos in der abendländischen Musikgeschichte’, Concerto, 164 (2001), 19–24, updated 2018: https://www.academia.edu/37112772/Zur_Rolle_des_Gesangsvibratos_in_der_Musikgeschichte; Robert Toft, Bel Canto: A Performer‘s Guide (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 92ff. See also a recent dispute on the subject of vibrato in historical singing based on two publications by Richard Bethell in the following blog: www.cacophonyhistoricalsinging.com/the-historic-record-of-vocal-sound-a-conversation-about-vibrato-with-richard-bethell (28 January 2024). See also Richard Bethell, Vocal Traditions in Conflict: Descent from Sweet, Clear, Pure and Affecting Italian Singing to Grand Uproar (Hebden Bridge: Peacock Press, 2019); Bethell, ‘The Historic Record of Vocal Sound (1650–1829) ’, NEMA Newsletter (2021), 30–83, and the online version of a lecture given by Richard Bethell at the conference Singing Music from 1500 to 1900: Style, Technique, Knowledge, Assertion, Experiment (Music Department of the University of York, 7–10 July 2009), www.york.ac.uk/music/conferences/nema/ (5 April 2023).

[35] Negative statements about vocal tremolo can be found in opera and concert reviews in the following Viennese newspapers between 1840 and 1860: Der Adler, 13 September 1842, 910; Wiener Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung, 2 September 1845, 420; Wiener Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung, 28 November 1846, 582; Wiener Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung, 16 March 1847, 131; Wiener Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung, 19 August 1847, 398; Oesterreiches Morgenblatt, 20 September 1847, 450; Wiener Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung, 21 September 1847, 454; Oesterreichisches Theater- und Musik-Album, 26. November 1847, 368; Oesterreichisches Theater- und Musik-Album, 5 December 1847, 584; Wiener Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung, 13 May 1848, 231; Humorist, 2 May 1852, 426; Oesterreichisch-kaiserliche Wiener Zeitung, 19 May 1853, 357, Neue Wiener Musik-Zeitung, 12 May 1853, 77; Humorist, 18. December 1853, 1159; Ost-Deutsche Post, 9 July 1854, (3); Ost-Deutsche Post, 21 January 1855, (1); Fremden Blatt, 22 April 1855, (5); Blätter für Musik, 25 November 1856, 379; Blätter für Musik, 24 April 1857, 131. In the Wiener Theater-Chronik, 28. February 1868, 45, a singer was finally praised for the absence of ‘disturbing tremolo’, and a final negative mention of vibrato is found in the same newspaper: Wiener Theater-Chronik, 8 December 1868, 244.

[36] Wiener Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung 104, 30 August 1845, 413: ‘die Manie der Bebung, dieses krankhaft überreizt erscheinende Vibriren des Tones, was bei so vielen Sängern der italienischen Schule bis zur überschwenglichen Überschwenglichkeit getrieben wird, mußten wir freilich, wo es sich um gesunde, frische Cantilene handelt, gänzlich beseitigt wünschen’.

[37] Leopold Alexander Zellner, ‘Musikalische Wochenlese’, Blätter für Musik Theater und Kunst 48, 17 July 1855, 90–91: ‘sie [vermeidet] durchgehends die Bebung (Tremolando) sie hält den auf die Klanghöhe gebrachten Ton ruhig und feststehend aus, ein Vorzug der nicht genug gewürdigt werden kann’. On Meyer-Dustmann see ‘96. Meyer-Dustmann, Luise’, Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich, vol. 18, (Vienna: Kaiserlich-königliche Hof- und Staatsdruckerei 1868), 160–61.

[38] E. Schelle, Die Presse, 1 May 1877, 2: ‘Allerdings war hier das Vibriren auf ein bescheidenes Maß zurückgeführt [ … ] Das Vibrato ist allerdings ein Kunstgriff, welcher, rechtzeitig angewendet, seine Wirkung nicht verfehlt’.

[39] See e.g. Livio Marcaletti, ‘Il cercar della nota: un abbellimento vocale ‘cacciniano’ oltre le soglie del Barocco’, Rivista Italiana di Musicologia, 49 (2014), 27–53.

[40] Zellner, ‘Musikalische Wochenlese’, 190–91: ‘Es ist nicht denkbar, daß der Mensch fortwährend in leidenschaftlicher Erregung sich befinde, es müssen auch Momente der Ruhe eintreten. Diese finden sich aber nie in dem Gesange Frln. Meyers. Sie ist beständig Empfindung, die sie durch Schleifen und Ineinanderziehen der Töne auszudrücken sucht. Zwar vermeidet sie durchgehends die Bebung (Tremolando), sie hält den auf Klanghöhe gebrachten Ton ruhig und feststehend aus, ein Vorzug der nicht genug gewürdigt werden kann; aber das selten unmittelbar geschehene Ansetzten der Töne ist eben so ein Fehler, welchen zu vermeiden Frln. Meyer sich wird müssen angelegen sein lassen’. Only representatives of the singing technique with fixed larynx refrained from using the cercar, as Julius Stockhausen makes clear: ‘Die Italiener nennen diese Art des Ansatzes cercar la nota – ‚das Suchen des Tones’. Man muss sie durch ein ruhiges und correctes Ansetzen der Consonanten, durch ein bestimmtes Einsetzten der Vocale von Anfang an bekämpfen’. (The Italians call this kind of approach cercar la nota – ‘the search for the tone’. It must be combated by a calm and correct placement of the consonants, by a certain insertion of the vocals from the beginning.) Stockhausen, Gesangsmethode, 18.

[41] See also Daniel Leech Wilkinson, ‘Portamento and Musical Meaning’, Journal of Musicological Research, 25 (2006), 233–61.

[42] For portamento in the performance of nineteenth century music in general, see Clive Brown, ‘Bowing Styles, Vibrato and Portamento in Nineteenth-Century Violin Playing’, Journal of the Royal Musical Association, 113/1 (1988), 97–128; Brown, Classical & Romantic Performance Practice 1750–1900 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 558–87; John Potter, ‘Beggar at the Door: The Rise and Fall of Portamento in Singing’, Music & Letters, 87/4 (2006), 523–50; Daniel Leech-Wilkinson, ‘Expressive Gestures in Schubert Singing on Record’, The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics 18/33–34 (2006), 50–70; Leech-Wilkinson, ‘Portamento and Musical Meaning’; Mark Katz, ‘Portamento and the Phonograph Effect’, Journal of Musicological Research, 25/3–4 (2006), 211–32; Raymond Monelle, ‘The Orchestral String Portamento as Expressive Topic’, Journal of Musicological Research, 31/2–3 (2012), 138–46; Kai Köpp, ‘Die hohe Schule des Portamento – Violintechnik als Schlüssel für die Gesangspraxis im 19. Jahrhundert‘, dissonance 132 (2015), 16–25.

[43] Johannes Andreas Gleichmann, ‘Ueber Manier und Mode in der praktischen Musik, hauptsächlich beym Violinspiel‘, Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 11, 16. March 1814, 175–76: ‘Das Durchziehen der Töne, diese in dem Gesange gewiss angenehme Manier, wenn sie nämlich mit grosser Mässigung, am rechten Orte und mit Geschmack angewendet wird, und welche dann vom Gesange in die Instrumentalmusik mit Recht übertragen worden war, wurde an einem Orte, wo die Tonkunst in einem hohen Grade blüht, (in Wien,) von Violinspielern dermassen gemissbraucht, dass sehr achtungswerthe Männer (wie Salieri) daran ein Gräuel fanden, und daher, so weit ihr Wirkungskreis ging, ein … förmliches Verbot dagegen, wenigstens beym Orchesterspiel, wohin es denn freylich auch am wenigsten gehört, einlegten … Wollte man dies auch auf das Solospiel ausdehnen, so dürfte es nun wieder etwas zu strenge verfahren seyn, und es würde durch die Vertilgung dieser Manier, nach dem alten Sprichwort, das Kind mit dem Bade ausgeschüttet werden. Wer hört wol jetzt einen guten Gesang ganz ohne dieselbe?’

[44] On portamento in Viennese vocal treatises of Schubert’s time, see Bernhard Rainer, ‘The Vocal Tutors by Swoboda and Rösner and Their Relevance for Ornamentation in Schubert’s Lieder’, Music & Practice, 9 (2021) www.musicandpractice.org/the-vocal-tutors-by-swoboda-and-rosner-and-their-relevance-for-schuberts-lieder/ DOI: 10.32063/0901 (6 April 2023).

[45] Glissando-like portamenti were decisively rejected in Vienna around 1800. Antonio Salieri even had a manifesto published repeatedly in this regard. Anon., ‘Brief von Antonio Salieri’, Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 12 (20 March 1811), 207, and Eduard Hanslick, Geschichte des Concertwesens in Wien (Vienna: Wilhelm Braumüller, 1869), 233/34. In the last third of the nineteenth century, however, portamento may have developed more and more in the direction of glissando. Early recordings show evidence of such use. A connection with the changes in vocal technique in the course of the century can be assumed.

[46] See, e.g., Johann Friedrich Agricola and Pier Francesco Tosi, Anleitung zur Singkunst (Berlin: George Ludewig Winter, 1757), 233–34; Johann Adam Hiller, Anweisung zum musikalisch-zierlichen Gesange (Leipzig: Johann Friedrich Junius, 1780), 53; Johann Friedrich Schubert, Neue Singe-Schule (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1804), 56–57; Ambrosio Minoja, Ueber den Gesang – Sendschreiben an B. Asioli (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1815), 25; Friedrich Dionys Weber, Allgemeine theoretisch-praktische Vorschule der Musik (Prague: Marco Berra, 1828), 82; Christian Gottfried Nehrlich, Gesang-Schule für gebildete Stände (Berlin: the author, 1844), 102; Auguste-Mathieu Panseron, Methode de vocalisation. Neueste, vollständige Gesangschule der Conservatorien zu Paris, Brüssel und Neapel (Cologne: Eck & Comp., ca. 1845), 20.

[47] On the ‘German stage ideal’ pursued above all by Ignaz von Mosel, Milder-Hauptmann’s ‘genuinely German singing’ and Vogl’s ‘declamatory singing’, see Martin Günther, Kunstlied als Liedkunst: Die Lieder Franz Schuberts in der musikalischen Aufführungskultur des 19. Jahrhunderts (Stuttgart: Franz Stainer Verlag, 2016), 146–72.

[48] The imperial and royal court actor Adolph Duprèe first publicly offered his services as a declamation teacher in 1816, see Der Sammler 150 (14 December 1816), 615. In the 1820s he also taught declamation to the successful singer Caroline Unger (1803–1877), see Allgemeine Theaterzeitung 178 (27 July 1842), 793.

[49] In 1829, the Vienna court theatre employed Josepha Gottdank as a teacher for mimic and declamatory instruction. Her position came in addition to the customary male and female singing teachers, thus emphasizing the attention on delivery, see Berliner Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung 6/18, 2 May 1829.

[50] Ignaz Franz von Mosel, ‘Die Tonkunst in Wien während der letzten fünf Decennien’, Allgemeine Wiener Musik-Zeitung 134 (9 November 1843), 566: ‘Schubert … hatte das Glück, sich gleich im Anfange seiner Laufbahn die Zuneigung des schon öfters erwähnten Hofopernsängers Vogl, dieses, ohne Widerrede, ersten declamatorischen Sängers unserer Zeit, zu gewinnen … Vogl leitete seine Wahl in Beziehung auf die Gedichte, declamirte ihm die Gedichte mit dem ihm eigenen hinreißenden Ausdrucke vor, der den Componisten schon auf die passendste Melodie zu führen geeignet war’.

[51] Otto Erich Deutsch, Schubert: Die Erinnerungen seiner Freunde (Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1983), 16: ‘[Vogl] welcher durch den ausgezeichneten deklamatorischen Vortrag seiner Lieder sehr viel dazu beitrug, sie bekannt und beliebt zu Machen, und Schubert selbst dadurch zu neuen Schöpfungen in diesem Fache begeisterte’. See also Günther, Kunstlied als Liedkunst, 369.

[52] From Vogl’s diary entries: ‘Nichts hat den Mangel einer brauchbaren Singschule so offen gezeigt, als Schuberts Lieder’ (Nothing has shown the lack of a proper singing school so openly as Schubert’s Lieder), in Eduard Bauernfeld, ‘Erinnerungen an J. M. Vogl’, Allgemeine Theaterzeitung 107 (5 May 1841), 477, and: ‘Die Erfahrungen, die sich ihm [Vogl] als Opernsänger und später als Gesangslehrer darboten, sammelte er im reifen Alter zu einem Werke, welches leider unvollendet blieb’ (The experiences he [Vogl] had as an opera singer and later as a singing teacher, he gathered at a ripe old age into a work which unfortunately remained unfinished.), Bauernfeld, ‘Erinnerungen an J. M. Vogl’, 478. Ignaz Mosel laments the loss of the declamatory and dramatic singing method as follows: ‘ein Verlust, der um so mehr zu beklagen ist, als es meinem dringenden und wiederholten Zureden nicht gelang, ihn zu bewegen, ein Lehrbuch für declamatorischen und dramatischen Gesang zu schreiben, das niemand so, wie er, zu verfassen fähig gewesen wäre’ (a loss which is all the more to be lamented as my urgent and repeated coaxing did not succeed in persuading him to write a tutorial for declamatory and dramatic singing which no one would have been able to write as he did), Mosel, ‘Die Tonkunst in Wien’, 366.

[53] Rösner’s first part of the second volume of his method, in which the treatise on pronunciation appears, can be dated to around 1835 and thus presumably falls into the period of Mosel’s efforts to persuade Vogl to publish a tutor.

[54] On Rösner and his connections to the Viennese German singing school see: Rainer, ‘The Vocal Tutors by Swoboda and Rösner’.

[55] Rösner, Leitfaden einer Gesanglehre vol. 2/1, 18: ‘Die Endconsonanten, besonders die zusammengesetzten, bekommen allemal einen kurzen Abschnitt durch das Nachschlagen der Zunge, damit sie mit dem darauf folgenden Worte, besonders, wenn dieses mit einem Vocale anfängt, nicht zusammen fliessen, und somit dem Zuhörer unverstandlich werden: z. B.: Munter und fröhlich erwachen am Morgen, alle Geschöpfe zur Arbeit gestärkt. Und nicht: Munterund fröhlicher wachenam Orgen, alle Geschöpfe zurarbeit gestärgd. [folgt Notenbeispiel 1] … vorzüglich darf kein Endconsonant verschlungen werden, oder undeutlich ausgesprochen werden, sondern er muss mit der Zunge vernehmlich nachgeschlagen werden, wodurch ein kleiner Absatz entsteht: z. B.: Wer begreift das Werk der Allmacht, wer die Langmuth unsers Schöpfers? Und nicht: Wea begreif das Weag dea Allmachd, wea die Langmuhd unseas Schöpfeas? … Wenn in einem Worte der Consonant zwischen zwei Vocalen steht, so wird er nach der Regel zur nächsten Sylbe gezogen: z. B.: wa_chen, und nicht wach_en. Wenn aber bei zusammen gesetzten Worten zwei Consonanten zwischen zwei Vocalen stehen … so dürfen die Consonanten nicht zur folgenden Sylbe gezogen werden, z. B.: wach_auf, und nicht wa_chauf’. Similar pronunciation rules are found in German instructions for stage actors and declamers of the time, see August Wilhelm Iffland, Theorie der Schauspielkunst, vol. 2 (Berlin: Neue Societäts-Verlags-Buchhandlung, 1815), 46–47, Johann Carl Wötzel, Grundriß eines allgemeinen und faßlichen Lehrgebäudes oder Systems der Declamation nach Schocher’s Ideen (Vienna: Stöckholzer u. Hirschfeld, 1814), 199, Heinrich Theodor Rötscher, Die Kunst der dramatischen Darstellung (Berlin: Wilhelm Thome, 1841), 147.

[56] Bauernfeld, ‘Erinnerungen an J. M. Vogl’, 473: ‘Dafür machten ihm [Vogl] die Gegner desjenigen, was wir Deutsche vorzugsweise dramatische Gesangskunst nennen, häufig den Vorwurf, er vernachlässige allzusehr den bindenden flüssigen Gesang, welchen etwa die Arie erfordert’ (On the other hand, the opponents of what we Germans prefer to call dramatic singing often reproached him [Vogl] for neglecting too much the binding, fluid singing that arias, for example, require). A discussion on whether the more frequent consonants in the German language compared to Italian make it less suitable for singing was already held in the eighteenth century. In the nineteenth century, some authors saw the richness of consonants and diphthongs in the German language as a positive factor, as they tended to give it a special colourfulness, see Trummer, Sprechend singen, singend sprechen, 160–72.

[57] Rösner, Leitfaden einer Gesanglehre, vol. 2/1, 18: ‘Überhaupt soll man, um recht deutlich auszusprechen und verstanden zu werden, alle Noten auf welche ein, zwei oder gar drei Mitlaute kommen, immer etwas kürzer singen, als der eigentliche Werth der Note gilt’.

[58] Swoboda’s Gesanglehre explains the pronunciation of singing for German, Italian, and Latin, Müller’s tutor does so for German, Italian, and French; see Swoboda, Gesanglehre, 13, and Adolf Müller, Neue vollständige Gesangschule (Vienna: Tobias Haslinger’s Witwe und Sohn, 1844), 72–77.

[59] Laurenz Weiss, Theoretisch-practische Gesang-Schule für das Conservatorium der Musik in Wien (Vienna: A. Diabelli u. Comp., 1842).

[60] Friedrich Schmitt, Große Gesangschule für Deutschland (Munich: the author, 1854), 72; Ferdinand Sieber, Vollständiges Lehrbuch der Gesangskunst (Magdeburg: Heinrichshofen, 1856), 90; Franz Hauser, Gesanglehre für Lehrende und Lernende (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1866), 84.

[61] Oskar Guttmann, Gymnastik der Stimme, gestützt auf physiologische Gesetze (Leipzig: J. J. Weber, 1861), 93: ‘Ein großer Fehler ist das Herüberziehen des letzten Konsonanten eines Wortes zu dem anfangenden Vokal des nächsten Wortes. Man darf dies durchaus nicht … Z. B. hören wir anstatt: Graf Eberhard entweder: Gra Feberhard, oder … Gra Weberhard. Dies ist nur eine Undeutlichkeit; einen vollständig anderen Sinn jedoch vernehmen wir in Folgendem: “seit ich” hören wir fast überall als: “sei dich”; ebenso: gute Nabend statt guten Abend; ferner: um un dum statt: um und um, und wa sist statt: was ist, u. s. f.’

[62] Thuiskon Hauptner, Methode der Gesangskunst, 104, cited after Bernd Trummer, Sprechend singen, singend sprechen: Die Beschäftigung mit der Sprache in der deutschen gesangspädagogischen Literatur des 19. Jahrhunderts (Hildesheim: Olms, 2006), 252: ‘Man singe: Im-Opfer und nicht Im-mopfer [man singe] Macht – alles [und nicht] Mach-talles … ’.

[63] Gustav Engel, Die Consonanten der deutschen Sprache: Ein Beitrag zur Lehre von Gesang- und Rede-Kunst (Berlin: Wilhelm Hertz, 1874), 100–108.

[64] Stockhausen, Gesangsmethode, 50: ‘Will man ein getragenes Stück mit Text singen, so bleibt die Hauptbedingung die, dass man jeder Note und jeder Silbe ihren vollen Werth gebe. Das Abbrechen der Note, das zu lange Verweilen auf einem Consonanten, die Verdoppelung desselben, wo er einfach angesetzt werden sollte, zerstört die Wirkung des gebundenen Vortrags ganz und gar’. In this light, Leopold von Sonnleithner’s negative statements on the declamatory performance of Schubert’s lieder, as addressed by Eric van Tessel, should be viewed in a differentiated manner. See Eric van Tassel, ‘“Something Utterly New”: Listening to Schubert Lieder, 1: Vogl and the Declamatory Style’, Early Music 25/4 (1997), 702–14, at 702–8. Sonnleithner apparently recorded his thoughts in 1860 under the impression of the first complete performances of Schubert’s cycle Die schöne Müllerin in Vienna in May 1856 and 1860 by the same Julius Stockhausen. Leopold von Sonnleithner, ‘Bemerkungen zur Gesangskunst V’, Recensionen und Mittheilungen über Theater und Musik, 45 (7 November 1860), 697–701, at 700–701: ‘Wir haben in solcher Weise den ganzen Kreis von Schubert’s Müllerliedern in einem Concerte mit dem größten Erfolg vortragen gehört, und zwar ohne allen dramatischen Anflug, ohne willkürliche Störung des Zeitmaßes, ohne Gefühlsübertreibung und Affektation. … Schubert forderte daher vor Allem, daß seine Lieder nicht sowohl deklamirt, als vielmehr fließend gesungen werden, daß jede Note mit gänzlicher Beseitigung des unmusikalischen Sprachtones der gebührende Stimmklang zu Theil, und daß hiedurch der musikalische Gedanke rein zur Geltung gebracht werde’ (We have heard the entire cycle of Schubert’s Müllerlieder performed in such a manner in a concert with the greatest success, without any dramatic touch, without arbitrary disturbance of time, without exaggeration of feeling and affectation. … Schubert therefore demanded above all that his songs should not be declaimed, but rather sung fluently, that every note should be given the proper vocal sound with the complete elimination of the unmusical tone of speech, and that the musical idea should be purely emphasised in this way). In 1829, however, Sonnleithner had still explicitly praised Vogl’s declamatory style of performance. See Deutsch, ‘Schubert: Die Erinnerungen seiner Freunde’, 16: ‘[Vogl] welcher durch den ausgezeichneten deklamatorischen Vortrag seiner Lieder sehr viel dazu beitrug, sie bekannt und beliebt zu machen, und Schubert selbst dadurch zu neuen Schöpfungen in diesem Fache begeisterte’ ([Vogl] who, through the excellent declamatory performance of his songs, did much to make them known and popular, and thus inspired Schubert himself to new creations in this field). Sonnleithner’s contradictory statements can best be explained by changes in aesthetic ideals during the critical decades of vocal pedagogy in the middle of the nineteenth century. In any case, his later opinion in this regard does not appear to be a relevant source on the intention and performance practice of Schubert’s songs during the composer’s lifetime. On Vogl’s Schubert Interpretations see also Walter Dürr, ‘Schubert and Johann Michael Vogl: A Reappraisal’, 19th-Century Music, 3/2 (1979), 126–40.