“New concert formats”: experimental performance practice in Cuckoo Land – a narrative recital with animated film and multimedia

DOI: 10.32063/1106

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Emancipated Performer

- Determining a conceptual framework

- The concept and its creation process

- Technology in favour of narrative action

- Communicating to a young audience

- Lyrical Narratives

- Completing the structure

- Spatial configuration and scenography

- The outcome

- Beyond the performer role – the emancipated performer

- Appendix

Nívea Freitas

Nívea Freitas, soprano, is currently a first year doctoral student at the ESMU-UFMG/Brazil. In 2018, she completed her Konzertexamen at the Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hamburg, where she also earned a second master’s degree in lyrical singing.

by Nivea Freitas

Music & Practice, Volume 11

Reports & Commentaries

Introduction

In this article, I describe the creative process of the Cuckoo Land – A Narrative recital with animation film and multimedia project. This production emerged in the context of a competition promoted by the CLAB Festival 2018 (Neue Konzertideen Festival), in the city of Hamburg, Germany, where the participants were encouraged to develop concert proposals that would bring innovative concepts and transformative perspectives.

As a classical singer, I began considering what new configurations or creative ideas could be applied on the production of art songs recitals: A new spatial distribution of the musicians? Exploring new spaces other than theatres? The interaction of new technologies with traditional repertoires? Dialogue with other media, whether technological or not, such as audiovisual projections or interarts, such as dance or theatre? A new audience distribution configuration? I knew, I wanted to craft a dramatic structure within a defined context, that would allow us to tell a story through the songs.

As I will explain more fully below, my creative process was inspired by an opera, Die Vögel (‘The Birds’, 1920), by Walter Braunfels. Die Vögel is based on a play of the same name by Aristophanes, which presents a utopian narrative in which its two main characters, discontented with life in their homeland, embark on an endeavour to construct a land in the clouds: Cloud Cuckoo Land, where they live in a manner akin to birds.[1] The dramaturgy was adapted into a shorter, contemporary version of the theatrical piece, with the narrative text crafted from the lyrics of lieder by Braunfels and other composers. Central to the story-telling and the atmosphere, was the addition of video animation (by Natalia Freitas), and even hand folded paper birds (origami). In addition to detailing my creative process, I argue that by broadening their creative horizons, performers can generate new professional opportunities to themselves and provide new interpretative possibilities to music, by placing it in new contextual frameworks.

Video 1 Concert Teaser

Emancipated Performer

In a census report published in 2023 by the United Kingdom’s musician support fund, Help Musicians, the disjunction between the high level of training observed among musicians and their capacity to sustain themselves solely through their income from musical pursuits is pointed out:

The first Musicians’ Census found that 70% of professional musicians in the UK hold a degree or higher … Over half (53%) sustain their career by sourcing other forms of income outside of music – two thirds (62%) of these generate additional funds from alternative employment, but other sources of financial support include support from family and friends (14%), and Universal Credit or other benefits (12%). Three quarters (75%) of those who have other income in addition to music report only seeking this work for financial reasons.[2]

Few musicians, particularly classical singers, belong to the category of “musicians with a fixed contract” or musicians whose schedule of “freelance contracts” secures year-round employment, considering the multitude of artists graduating globally each year. The reality is a myriad of highly specialized professionals with exceptional academic qualifications who, in parallel with their daily dedication to the development of their techniques and professional practices, often need to seek ways to sustain a viable livelihood, sometimes venturing into other fields.

On the other hand, in an attempt to augment the generation of opportunities for these musicians, the encouragement of the emergence of a new creative professional, termed by Paulo de Assis as the “emancipated performer” (in a reinterpretation of the concepts developed by the French philosopher Jacques Rancière in his work Le Spectateur Émancipé), could potentially contribute not only to income generation for diverse musicians, thereby impacting the entire creative chain, but also to the development of creative proposals that could potentially contribute to the cultivation of new audiences for concert music.[3]

An initial challenge that I faced in the preparation stage of Cuckoo Land was dealing with my limiting preconceptions about what I could or could not propose in relation to the chosen repertoire, as well as the fear of possible judgments from the other artists and the public. I realized that conventions and the perceived limitations of adhering to a ‘reified’ work was also ingrained in me – and that in order to have the creative freedom necessary to execute my proposal, I needed to first appropriate other possible readings about the relationship between performers and musical works.

Moreover, there are clear differences between preparing an interpretation of a single piece of music and preparing a set of pieces to be presented in the context of a concert that has some specific concept or format in itself. For a lied cycle, an oratorio, an opera, among others, preparation, knowledge and specific interpretative work are required to execute each of these formats. Generally, it is not the responsibility of the singer or any participating musician to undertake functions other than the act of performing. Whereas the context for an opera or an oratorio is given, and the duration more or less suitable for an evening performance, the problem is different with short lied cycles or single art songs. In order to perform them successfully, the context must actually be created – they need a new format.

What if singers or instrumentalists, instead of waiting for an invitation to work as performers, became creators of their own concert proposals, even inventing new formats whenever necessary? That’s something rarely seen being proposed by classical singers.

Without ignoring the extra effort this would put on a musician who needs to focus on performance, this could well be a plausible means of extending work opportunities for those who can identify with the role of being interpreter-creators. Such a model would foster musicians’ creativity to extend their own work opportunities, while introducing authentic concepts that engage in novel interpretative avenues within their artistic pursuits.

With this emancipated spirit, breaking free from various layers of ideologically constraining influences, and desiring to open a new avenue of engagement for myself, with the generation of potential new opportunities, I allowed myself to take on the role of the creator of my own concert proposal for a performative narrative. Winning the Clab Festival competition provided the funding for the concert’s production. However, had there been no monetary prize, alternative avenues for financial support could have been explored. Options include applying for various government cultural funding programs, seeking private sponsorship directly from enterprises, or even initiating a public financing project through crowdfunding.

Determining a conceptual framework

Like someone playing with the creation of paper mâché dolls, before assembling the various blocks of dampened paper, plaster coating, and paint, I initially devoted myself to the elaboration of what would be the framework for the ‘new concert concept’ proposal. For the construction of this foundation, I needed to address the following questions: What kind of material would I use? What artistic criterion or decision would guide the organization of the chosen material? Whom did I want to communicate with? What did I want to communicate? Addressing these questions and others that arose constituted the path that guided the subsequent developments.

In the semester preceding the initiation of the Cuckoo Land project, I was introduced by the Costa Rican soprano Iride Martinez to the work of the German composer Walter Braunfels (1882–1954), specifically his opera Die Vögel (The Birds, 1920) – which she had the opportunity to perform in a 1998 production at the Cologne Opera. The opera is the composer’s adaptation of the Greek play of the same title from 414 BCE by the Athenian playwright Aristophanes. Enchanted by its musical language, I delved into further research on Braunfels’ work. Among various materials from his compositional career, I encountered two song cycles: Fragmente eines Federspiels (Fragments of a Feather Game, 1904) and Neues Federspiel (New Feather Game, 1907). The former consists of eight texts, while the latter comprises nine, all centered around the theme of birds and drawn from the folk song collection Des Knaben Wunderhorn.[4]

The presence of the ‘birds theme’ in the composer’s works caught my attention and encouraged me to learn more about the Aristophanes’ play that inspired the libretto of Braunfels’ opera, and also the texts selected for his two song cycles. The 17 texts selected for the two song cycles are simple and mostly short poetic texts that describe various birds, whose names also give title to each piece (the exceptions are for the third piece of the 1904 cycle ‘Das Immlein (The Bee) and first piece from the 1907 cycle, ‘Engang’ (Entrance)).[5] The songs are short, some lasting a little over a minute, others even shorter, so the the two cycles take barely twenty minutes to sing.

This acquaintance with both Braunfels’ work and the theme of birds, particularly in relation to Aristophanes’ theatrical narrative, led me to the decision to use them as inspirational material for constructing the conceptual framework. However, before completing my choice of repertoire, I wanted to develop a methodological argument. I was inspired by Constantin Stanislavski, whose work I already knew,[6] and his view of art songs as composed with ‘disjointed’ texts that could be thought of, according to the imaginative freedom of each performer, as part of a larger narrative, articulated by a character and context of their free choice. In an extrapolation of this idea, I then considered, in the conception of Cuckoo Land, that the freedom that this methodology recommends, could be thought of not only as a creative studio exercise, but as a possible way of interacting with this repertoire beyond the way it is usually done in conventional performance practices of the genre.

I committed to crafting a contemporary adaptation of Aristophanes’ play, incorporating art songs for soprano and piano as the musical material for constructing my version of this narrative. In addition to the songs by Braunfels, various pieces by other composers were selected based on criteria.

The concept and its creation process

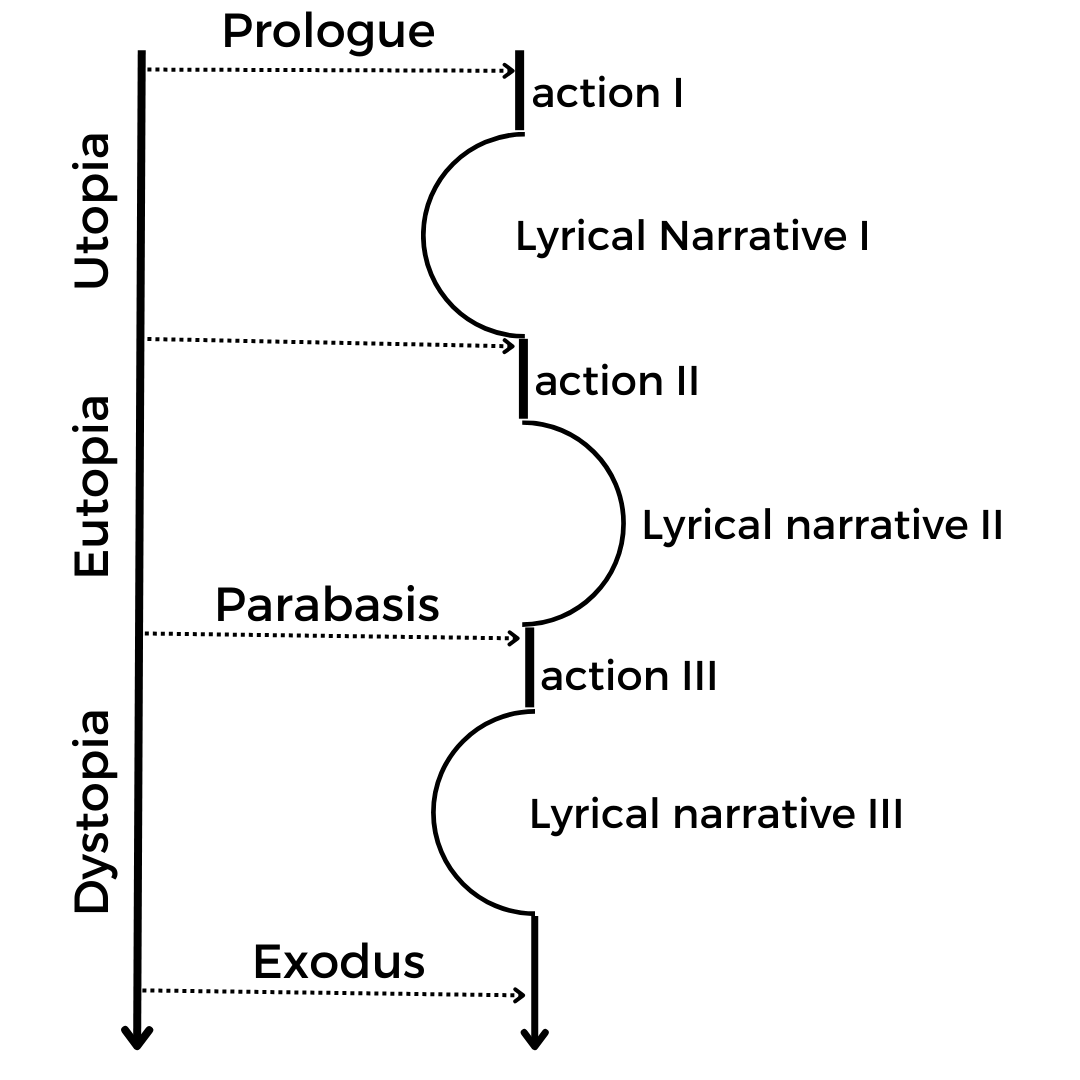

With this direction in mind, I initially dedicated myself to forming a deeper knowledge not only of Aristophanes’ play, but also of the history of Greek theater and how the dramatic structure of theatrical plays of his time took place. The typical narrative structure of Aristophanic comedies is shown in Figure 1.

| Section | Description |

| Prologue | Monologue or dialogue, which precedes the entrance of the choir, where the scope of the piece is presented. |

| Parody | Entrance of the choir, using masks, which normally represents the demonstration of the people in the dramatic context of the work. |

| Agon | Debate, normally between two characters, in a clash of rhetoric, in which, in the end, there is a “winning” speech. |

| Parabasis | New entrance for the choir, with the removal of masks, where what is sung is aimed at direct dialogue with the audience. |

| Episode | Dramatic development resulting from the outcome of Agon. |

| Exodus | Return of the choir singing a song, generally of a festive tone, to close the piece. |

Figure 1 Typical structure of theatrical plays from the period of Aristophanes.

Equipped with the results of my research and immersion in the chosen foundation material, I outlined the initial framework of what would constitute my concert proposal as a form (Figure 2):

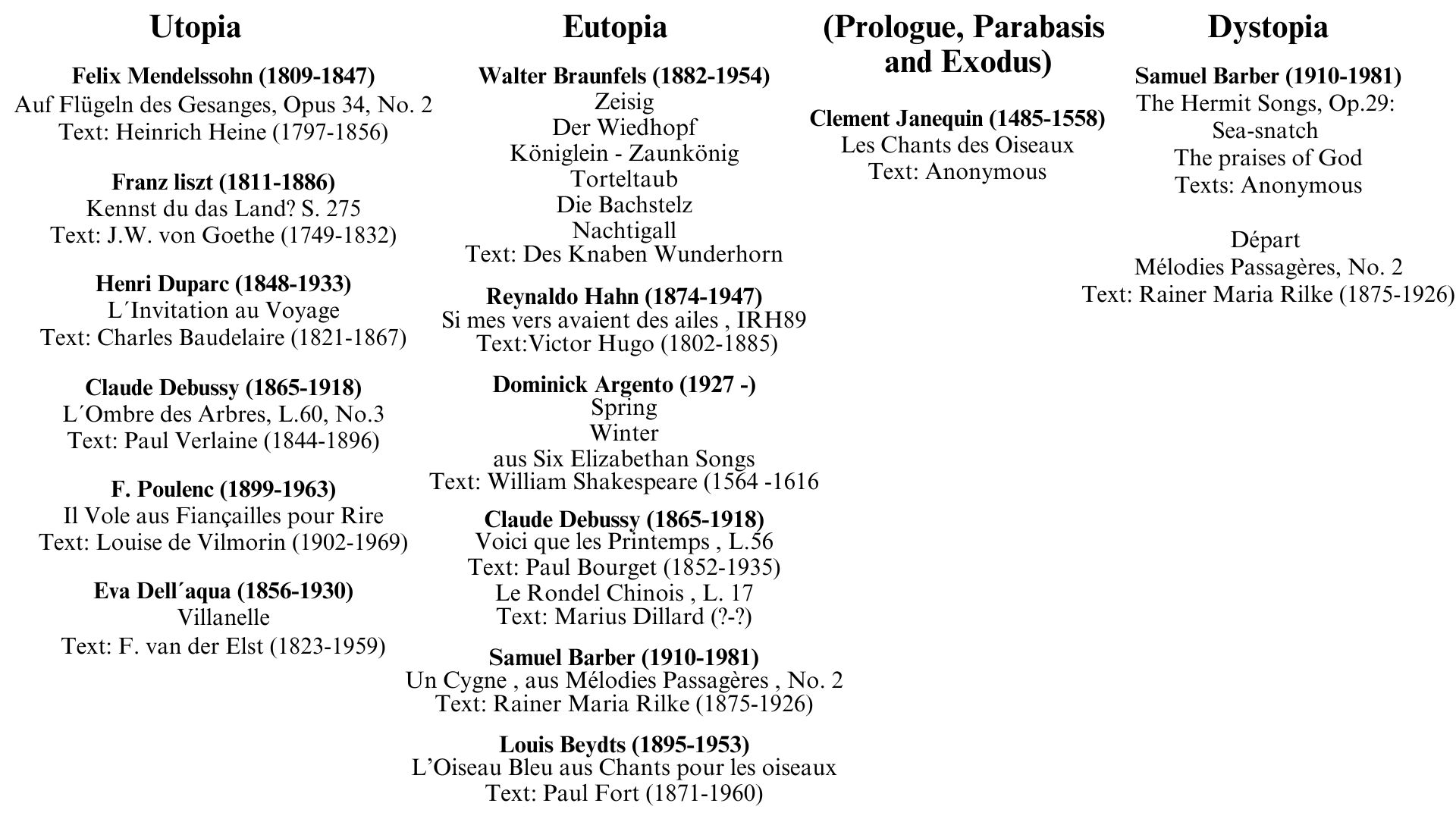

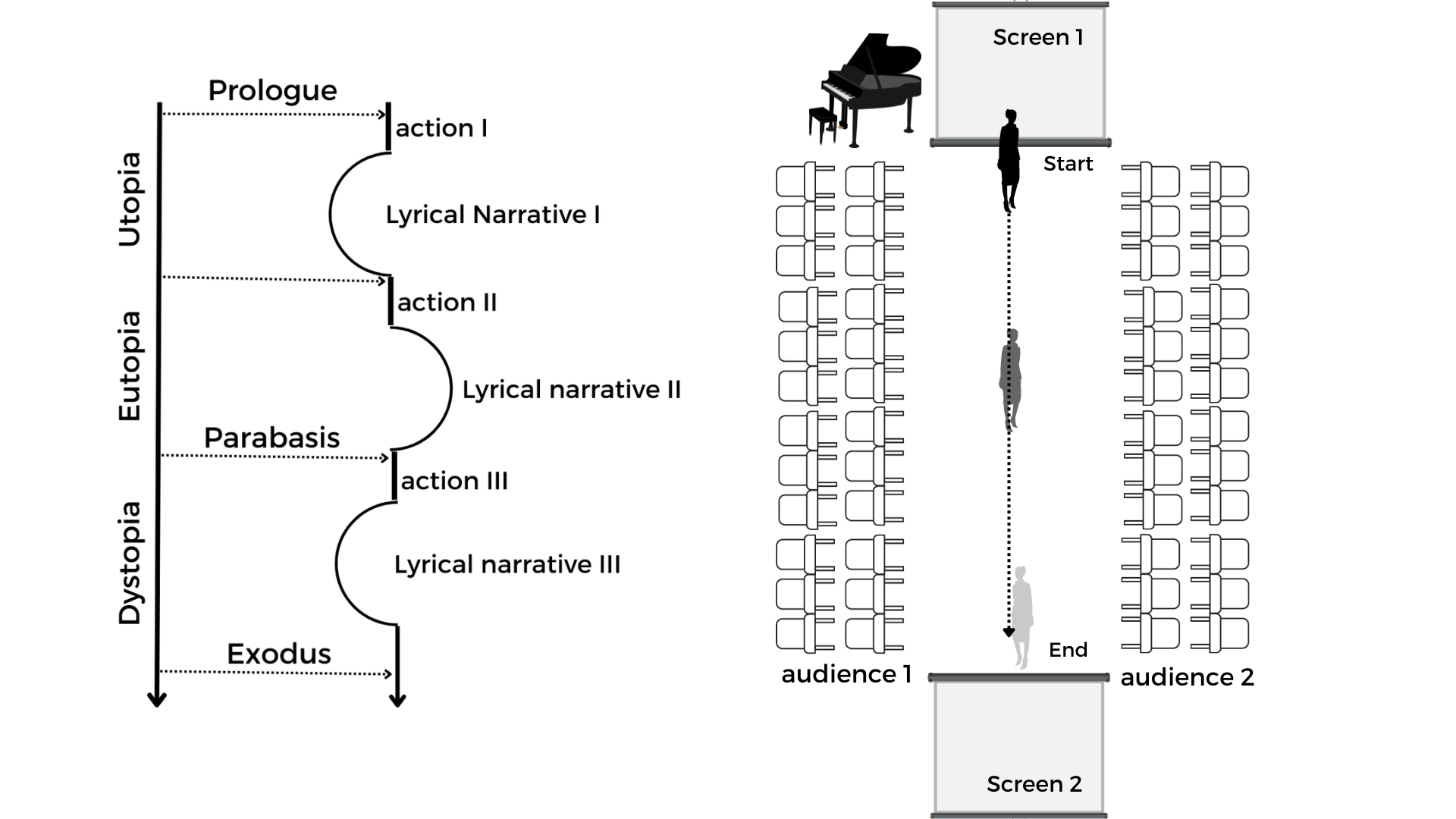

Figure 2 shows how I visually sketched out my concept. The arrows in the figure represent the direction in which the temporal development of the scenes of this narrative-concert proposal would take place. The segments labelled as Action I, II, and III are instances of animated film that punctuate the concert sequence, providing pivotal moments where the narrative unfolds visually. From Greek theater, I decided to keep three of its main forms, the Prologue, the Parabasis, and the Exodus, which form the beginning, middle, and end of the proposed dramatic arc. What I defined as Lyrical Narratives I, II and III, are the three moments in which the dramatic action acquires a literally lyrical arc, where the chosen songs would be introduced. Conceptually, the concert was also divided into three parts: Utopia, Eutopia and Dystopia.

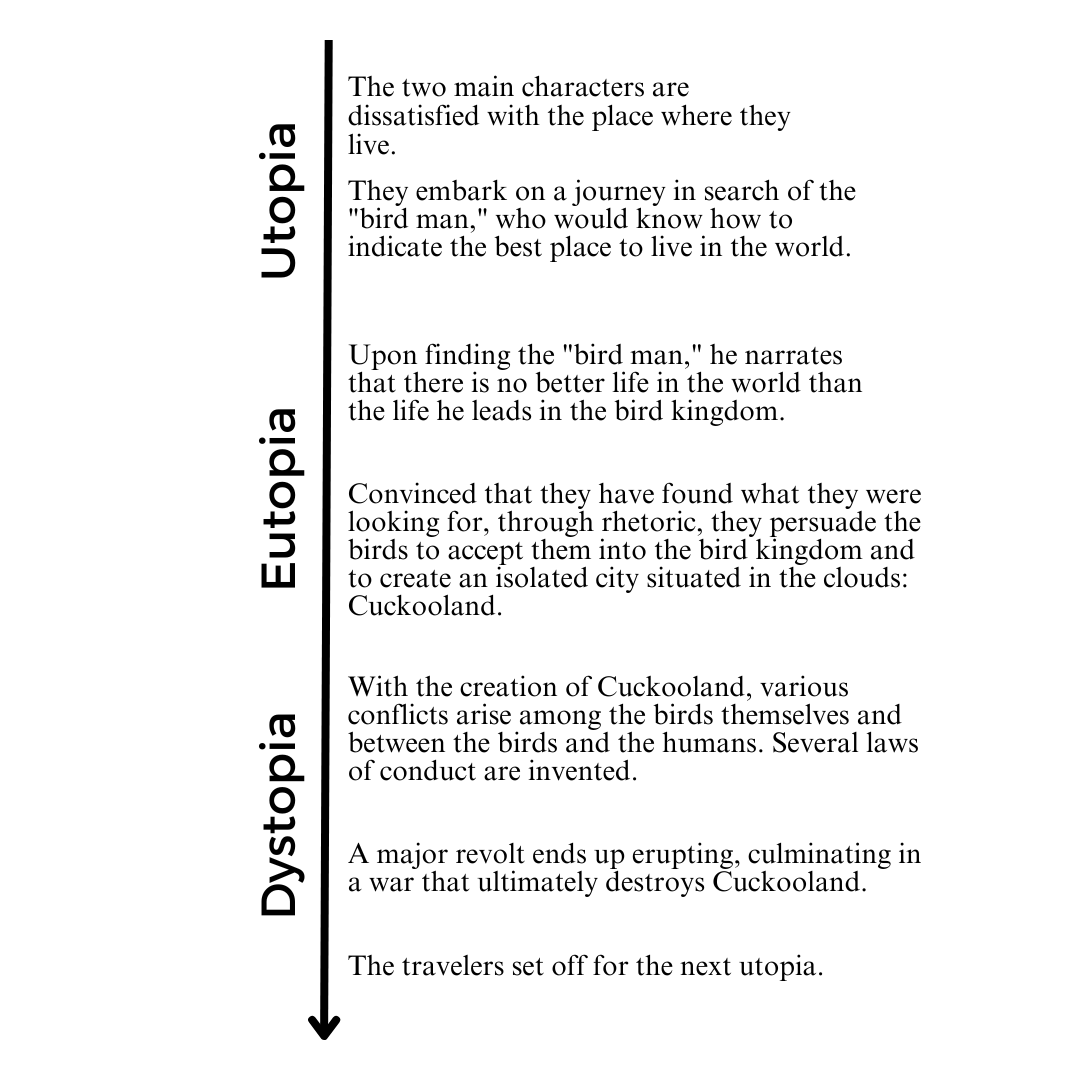

The word ‘utopia’ was coined by Thomas More in 1516, but the argument of Aristophanes’ Birds is associated as the first conceptual representation of the term.[7] Cécile Corbel-Morana even identifies the development of the semantic transition in the play between a narrative that begins with a utopia, culminates in an eutopia and concludes with a dystopia.[8] Understanding the meaning of these three variations and how they actually summarize the essence of the narrative in each of these three moments was then what guided me in the conceptual division of my concert proposal.

The excerpts titled action I, II and III were defined as the moments in which the action would develop the narrative temporally.

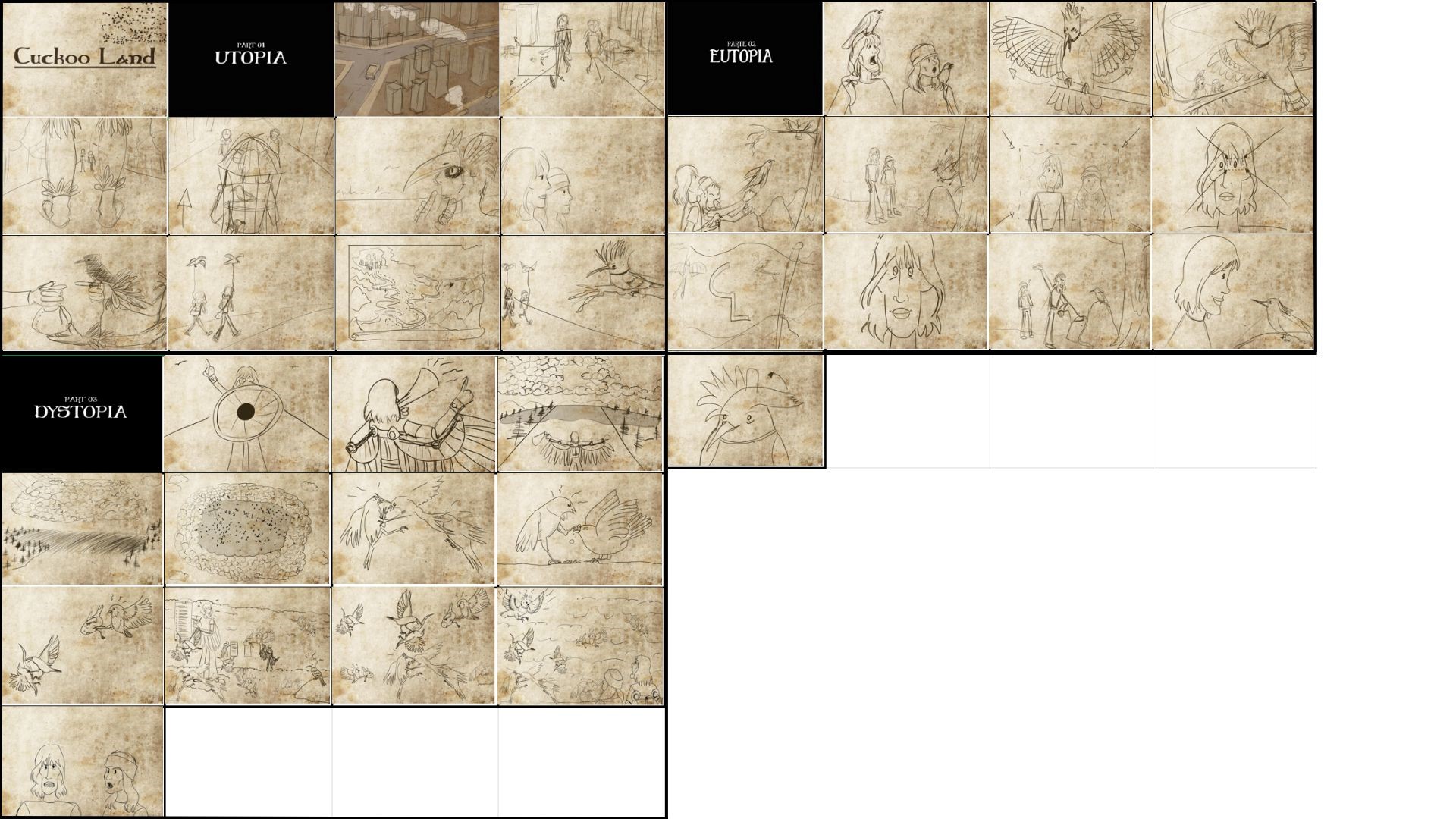

Technology in favour of narrative action

The tool I chose to relate this narrative, contextualizing each of the three arcs of the concert and thus creating the scenario with which the chosen songs would be interpreted, was animated film. Originally, I had hoped to carry out this work via interdisciplinary creative development, not only with the audiovisual universe, but also through partnerships with other performing artists such as actors and dancers. But this was a significant undertaking. And because my sister, Natalia Freitas, is a professional animator, and she and I have been looking for an opportunity to create something together for some time, I chose to work with her animation as a major factor in the project.

With my framework established, and lied and animated film chosen as primary resources, I could continue the process. I defined that action I, action II and action III would be brief animation insertions, lasting around two to three minutes each, that would help develop the narrative. When preparing the script for these three animations, I also followed the conceptual division of utopia, eutopia and dystopia. I extracted only the essentials to summarize in a few minutes what in Aristophanes’ original play fills two acts. The intention was to provide the public with something that could be read as a new experience that draws on interdisciplinary expressions.

It is outside the scope here to detail all the processes involved in the production of the animated film, such as scriptwriting, storyboard conception, aesthetic decisions, among other artistic direction matters. However, Figure 3 illustrates the process.

Communicating to a young audience

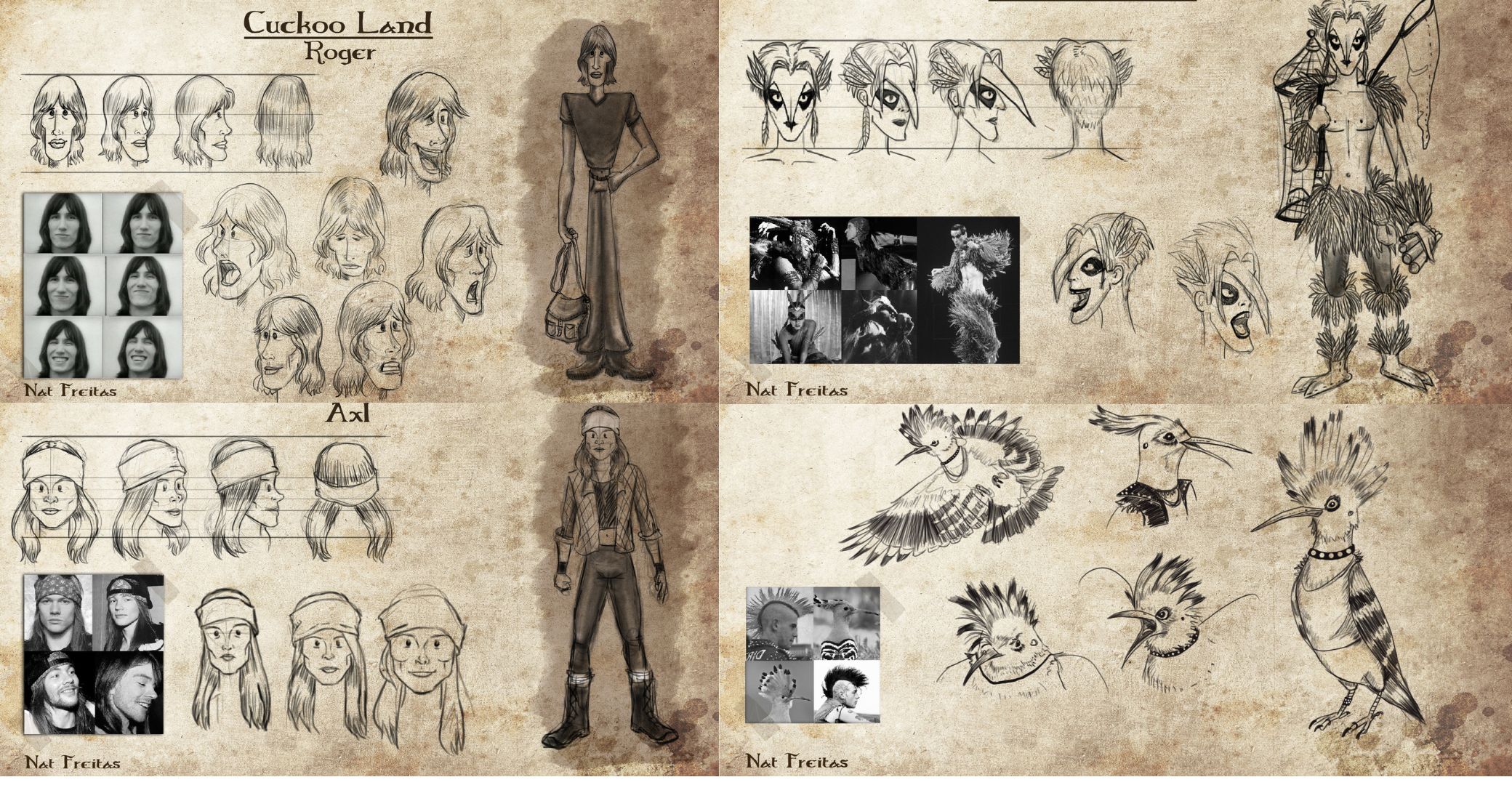

The selection of the animated film (Video 2) as an interdisciplinary resource to aid in conveying the proposed narrative, along with its entire development process and aesthetic choices, was conceived as a strategy for establishing a possible connection or fostering identification with the young audience or those not yet fully connected to concert music. The original characters from Aristophanes’ work (Pisthetaerus, Euelpides the bird catcher, and Tereus – the Birdman) underwent a reinterpretation with associations with characters already known from both the contemporary world of music (the two main characters became Axl and Roger), as well as lyrical narratives known from the world of opera (the bird catcher was renamed Papageno).

Video 2 Animation scenes

The main character, Roger, makes reference to the British musician, Roger Waters, from the band Pink Floyd, who, among other works, was known for the album, film and live show The Wall. This choice was made because at the end of Aristophanes’ play, the main character (Pisthetaerus) also decides to build a “wall” to separate the “world of birds” from the “world of men”. As I wanted to associate the characters in the play with the universe of contemporary popular music, the name of Roger Waters was chosen to replace the original Greek name. The second character (Euelpides), was associated with Axl Rose, from the band Guns N’ Roses, in connection with one of his best-known songs, “Paradise City,” which depicts a narrative of someone also in search of a paradise city to inhabit. The “bird catcher” character was a direct association with the character Papageno from Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute, due to the fact that he was also a ‘birdman’ and his visuals were inspired by the Brazilian pop singer, Ney Matogrosso. The king of the birds, who in Aristophanes’ play is a Hoopoe bird, due to its distinctive crest resembling a ‘mohawk’ hairstyle, I associated with the figure of a Punk. (See Figure 5).

Sound immersion was another element we used, during the public entrance, with the aim of introducing the audience to the sound atmosphere that would be presented along the concert. A musical score was composed by the Chinese composer Xiao Fu (who was also responsible for the animation soundtrack), and this ambience music was played, via a playback, from the moment the audience entered, until the beginning of the performance.

Lyrical Narratives

The interplay I proposed between action (with the animated film) and what I’ve defined as lyrical narratives (with the chosen songs) was aimed at imparting a dramatic function akin to the relationship between Recitative and Aria forms in baroque and classical opera. In actions I, II and III (Figure 1) the narrative develops temporally, while in lyrical narratives I, II and III, we have arcs of suspensions of lyricism and poetry that contextualize each of these pre-defined conceptual moments: Utopia, Eutopia and Dystopia.

Regarding the concept of utopia, I was inspired by the words of Cécile Corbel-Morana:

In fact, utopia is never a pure fantasy disconnected from reality: it is always constructed in reaction to reality, more precisely as a critique of a pre-existing state for which the utopian alternative offers a fantastic solution.[9]

Corbel-Morana argues that in this conceptual division developed in Aristophanes’ play, there is also the development of a chronology with utopia as the past that glimpses the future, eutopia as the realization of utopia in the present, and dystopia as the eutopia that went wrong in the future.[10] In other words, it is as if in this narrative we could experience the characters’ moment of dream (utopia), fulfilment (eutopia) and disillusionment (dystopia).

Leaning on this conceptual and chronological perspective, I was ready to choose the remaining repertoire (in addition to Braunfels), that would compose the musical body of the project. I summarized the play’s narrative schematically (see Figure 6).

Songs for utopia, the beginning of a journey where the characters set out to find the best place to live, had to share the themes of both birds and journeys in search of supposedly happier places. In other words, the criteria for selecting the songs was thematic, based on the text, without any criteria of style, period, or language. I chose six sings for this first part of the concert, including “Auf Flügeln des Gesanges,” by Felix Mendelssohn to a text by Heinrich Heine, and “L’invitaton au voyage” by Henri Duparc to a text by Charles Baudelaire.

The same reasoning was followed for the curation of the songs for the Eutopia and Dystopia sessions. In the former, we contextualize the characters’ spirit of achievement and their enchantment with the “world of birds”, with a selection of six songs by Braunfels – “Zeisig,” “Wiedehopf,” “Königlein,” “Torteltaub,” “Die Bachstelz,” “Nachtigall” (birds that also were represented in the animation) – and songs by other composers that also described birds or their habitat, or that referred to the theme of the human desire to resemble these beings in some aspect. Two examples that were part of the Eutopia session, are the songs “Si mes vers avaient des ailes,” by Reynaldo Hahn with text by Victor Hugo and “Nachtigall,” by Braunfels with text from Des Knabes Wunderhorn.

This second session was also the longest of the three, with a total of thirteen songs. The last session, Dystopia, is the shortest, with just three songs by Samuel Barber, whose texts address themes of destruction and disillusionment, in allusion to what also happens in the narrative of the animated film, (except for the last piece, which features a farewell text, from someone who will embark on a new journey, or “new utopia”).

Completing the structure

The sessions that we defined as Prologue, Parabasis and Exodus, were structured as follows: the Prologue, or monologue introducing the play, was delivered by the narrator, via the narration of the action film I – Utopia. These sessions, which refer to the structuring of Greek pieces from the Aristophanic period, in which a chorus enters to represent the voice of the people, we had the participation of three more singers, a mezzo, a tenor, a bass, and the pianist, who was also a soprano, where the a cappella quartet “Les Chants des Oiseaux,” by Clement Janequin, was performed, and this piece was also divided into three sessions. The first session of this quartet was sung in the concert’s prologue, the second in the session in Parabasis and the last in Exodus. The complete repertoire, chosen following all these previously clarified criteria can be seen in Figure 7.

Spatial configuration and scenography

On the occasion of the CLAB Festival, the winning proposals were given some different options to choose from for the performance space. These ranged from conventional theatres to locations that would offer more freedom for experimenting with new spatial configurations between musicians and audience. The space I chose for the Cuckoo Land performance was the Resonanz Raum, located inside the Bunker St. Pauli, in the city of Hamburg, Germany. The place was built as an air raid shelter in 1942, and today it houses several cultural initiatives. The Resonanz Raum hall, in addition to excellent acoustics and equipment, provides the opportunity to shape its space according to our artistic choices. For my project, I opted for a spatial configuration that resonates with the conceptual structure of the concert while simultaneously placing musicians and the audience in a non-conventional arrangement.

We developed a scenographic plan, albeit a simple one, at the suggestion of the festival’s production team, and this introduced a strategic element of engaging the audience by including the local community. The proposal included offering a free art workshop to the public, allowing them to learn a skill while creating objects that would be used in the concert’s scenography. As birds were the theme with the strongest visual appeal and conceptual connection to the project proposal, an Origami specialist volunteered to conduct the workshop, in which various paper birds were created. These were used not only for decoration but also as scenic elements throughout the concert. Figure 9–12 show the workshop, one of the rehearsals, and the concert, with the proposed spatial configuration, featuring the elements produced by the local community.

The outcome

After the premiere at Bunker St. Pauli, we held another performance at a different venue, the HFMT Hamburg Forum, and both concerts were very well received. All of us – the musicians and the production team – felt a significant sense of accomplishment and fulfilment. The alterations made to the audience configuration, along with the entire conceptual and practical structure of the concert, created an atmosphere of attention, engagement, and communication beyond what was expected.

For me, the entire process – the research, the creative conception of the project as a whole, the repertoire selection and preparation, and all the other aspects of the project – brought an additional layer of fulfilment and enjoyment as an artist. I could not only be the performer but also the creator. It was important to realize that even a small initiative, such as this one, can introduce a new concert concept, not only to the audience, but also to arts professionals including fellow musicians, technicians, producers, lighting crew, stage directors, and communication team. In other words, when performers emancipate themselves by generating their own performance opportunities, they not only help to promote concert music, but create a chain of benefits that impact local cultural market.

Introducing these songs into a new context – in this case, to narrate the Cuckoo Land story – provided a fresh perspective on them, both for me as the performer and for the audience familiar with the repertoire. Each song in this project acquired a new semantic function, leading to a novel musical interpretation. What Stanislavski proposed as an exercise, can serve as an infinite creative resource.

Beyond the performer role – the emancipated performer

A solo recital requires extensive musical and technical preparation as well as the memorization of the entire repertoire; in a performance such as Cuckoo Land, it also involves the extensive scenic work described here. When proposing this project, I was aware that I would subject myself to new responsibilities and demands beyond my usual work as a soprano. With this in mind, a concern from the outset was not to allow the demands of conceiving and producing the concert to encroach upon the time required for my musical and performance preparation. In order to ensure this did not happen, my pianist and I approached the preparation as if it were for a traditional recital, and we established a rehearsal schedule from the outset that allowed for a secure preparation of the entire repertoire.

The challenges inherent in preparing a song recital for voice and piano were compounded in the development of this project by the incorporation of nonmusical creative roles, such as scriptwriter, director, and producer, both for the animation production and the creation and execution of the concert itself. Assuming these roles was not difficult for me. I already had a desire to engage creatively in other areas of the arts to enhance my musical interpretation, not only in the auditory realm but also in connection to a broader expressive network. I understand, however, that this kind of involvement may prove more difficult for some performers than for others.

Careful planning is essential here, both to ensure each stage is completed on time and to carve out sufficient time for the musical rehearsals that are fundamental to the success of a musical performance. The process also taught me about people management, a skill not traditionally associated with performing artists. I initially found it challenging to understand that I needed to assume this role so that each stage was completed on time. We had just over six months for the preparation and execution of the project, so I allocated the first three months to the development of the animation film and the remaining months to the pre-production stage of the concert, with the final month dedicated to scenic and technical rehearsals. Musical rehearsals were conducted concurrently throughout the project development period. The performer who is interested in also working on the production of their own projects must be open to learning about various artistic languages, exhibit organizational acumen, and demonstrate sensitivity to collaborate effectively with others involved in the process.

A challenge that arose with this project was to distinguish my role as performer from my role as the director/producer during the actual concert performance. In hindsight, the first presentation of the concert would have been better if I had mentally prepared to set aside concerns about other demands, and focused solely on my role as a soprano-performer. The performance was successful, even though I felt tense and worried, but the second performance went more smoothly.

Being able to develop a project from start to finish made me feel empowered and capable. The role of performer offers a sense of accomplishment, especially when executing a repertoire we enjoy or when invited to participate in projects with professionals we admire, among other scenarios. But being able to present another expressive facet through a personal project of my own creation also proved to be very fulfilling.

The experience I gained in this project has served as encouragement and learning for further exploration. I developed Ophelia, the Hysterical (2021 in the context of isolation during the Covid 19 pandemic. And I am now undertaking doctoral work, with the aim of specializing even more in creative performance possibilities for performers, specifically singers like me.

Cuckoo Land served as a valuable laboratory and demonstrated that the creative possibilities of developing new formats using concert music, new technologies, and creativity are limitless.

Appendix

Performers and team

Concert

Nívea Freitas – Soprano

Jaerim Kim – Piano

Lisa Olsen – Mezzosoprano

Seungwoo Yang – Tenor

Joris Rubinovas – Bass

Ron Zimmering – Scene diretor

Taizhi Shao – Multimedia operator

Martin Schneider, Origami artist

Animated film

Nívea Freitas – Art Director and Script

Natália Freitas – Animation Director, Art concept and Animation

Johannes Flick – Animation & Animation coordination

Viktor Stickel and Ali Hashempour – Animation

Ingmar Grapenbrade – Voice narration

Tiago Calliari – Artistic Concept

Katharina Fröhlich – Dramaturgy

Mara Nitz – Dramaturgy

Xiao Fu – Musical Composition

Mareike Keller – Production

Clabfestival Production

Prof. Martina Kurth

Elisabeth Brunmayr

Marie Schnaidt

Florian Stracke

Johannes Dam

Endnotes

[1] ‘The name of the locality anticipates or determines the qualities of its residents … Clouds refer to the sky, the quintessential space for birds. The new city, located between heaven, earth and ether, hovers in the air like the birds that inhabit it. At the same time, the cloud, composed of water and air, points to the impalpable character of the city which, made of fog, is nothing. Cuckoo is a reference to Pisetero, a bird-man who usurped sovereignty from his legitimate heirs, the birds. In doing so, he behaves exactly like the cuckoo which, born in the nest of other birds, hatched and fed by adoptive parents, reciprocates this care by killing the real chicks so as not to have to share the food with them’ (my translation). Adriane da Silva Duarte, ‘A maior das maravilhas’, Classica 5/1 (1993), 97–110 at 107, https://doi.org/10.24277/classica.v5i1.547.

[2] Pohl Woods, The first ever Musicians’ Census report launched, www.helpmusicians.org.uk/about-us/news/the-first-ever-musicians-census-report-launched (accessed 23 November 2023).

[3] ‘The performer, much more than an interpreter, becomes an operator, machining new assemblages of things against the grain of their historically inherited constitutive parts … This “operator” (or “emancipated performer”) gains new functions both within music and within society at large, creating a space for performers to actively engage with the artistic, aesthetic and social problems of their time, to creatively suggest new modes of organizing materials and knowledge, and to contribute to wider transformations in the way society organizes and distributes artistic objects and activities’. Paulo De Assis. ‘Experimental Performance Practices: Navigating Beethoven through Artistic Research‘, Music and Practice, 8 (2020).

[4] Compilation of texts of medieval and folk songs in three volumes, gathered and published by Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano between 1805 and 1808.

[5] The 1904 cycle has the following songs: ‘Die Bachstelz’ (The Wagtail), ‘Der Gimpel’ (The Dom-hafe), ‘Das Immlein’ (The Bee), ‘Das königlein’ (The Wren), ‘Die Nachtigall’ (The Nightingale), ‘Die Schwalbe’ (The Swallow), ‘Der Wiedehopf’ (The Upupa), ‘Der Zeisig’ (The Siskin). The songs of the 1907 cycle are ‘Eingang’ (Entrance), Bachstelz (Wagtail), Fink (Finch), Gimpel (Bullfinch), Kohlmeise (Great Tit), Distelfink (Goldfinch), ‘Lerche’ (Lark), ‘Turteltaub’ (Dove), ‘Zeisig’ (Siskin).

[6] See Nívea Renata Alencar de Freitas and Luciano Monteiro de Castro Silva Dutra, ‘Um olhar sobre o trabalho de C. Stanislavski no estúdio de ópera (1918–1938): a canção de câmara como recurso cênico-pedagógico’ [A look at C. Stanislavki’s work in the studio of opera (1918–1938): chamber song as a scenic-pedagogical resource], XXVI Congresso da Associação Nacional de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação em Música (Anppom) (2016), https://www.academia.edu/36202447/A_Pespective_on_C_Stanislavski_s_Work_on_the_Opera_studio_1918_1938_The_Art_Song_as_a_Scenic_Pedagogical_Resource?source=swp_share. In this article, I highlight Stanislavski’s argument about the use of chamber songs as creative instruments for the elaboration of possible new narratives. See Constantin Stanislavski and Pavel Rumyantsev, On Opera (New York: Routledge. 1998). As a first approach with the studio singers, instead of direct character interpretation work via existing opera roles, Stanislavski proposed the use of art songs as a creative and expressive liberating resource for the actors.

[7] Rosanna Lauriola, ‘The Greeks and the Utopia: An Overview through Ancient Greek Literature’, Revista Espaço Acadêmico, 9/97 (2009), 109–124, and Antônio Medina Rodrigues, ‘Mito e utopia em as aves de aristofanes’, in Mito, Religião e Sociedade: atas do II Congresso Nacional de Estudios Clássicos, ed. Zelia de Almeida Cardoso’ (Sao Paulo: SBEC, 1991).

[8] Cécile Corbel-Morana, ‘L’imaginaire utopique dans la Comédie ancienne, entre eutopie et dystopie (l’exemple des Oiseaux d’Aristophane)’, Kentron, 26 (2010), 49–62, DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/kentron.1330.

[9] Corbel-Morana, ‘L’imaginaire utopique’: ‘L’utopie n’est en effet jamais fantaisie pure détachée du réel: elle se construit toujours en réaction à la réalité, plus précisément comme critique d’un état de choses existant auquel l’alternative utopique propose une solution fantastique.’

[10] Corbel-Morana (2010),’L’imaginaire utopique dans la Comédie ancienne, entre eutopie et dystopie (l’exemple des Oiseaux d’Aristophane)’, 51 . [Nivea: exact page number missing; please give the single page of the quote]

[11] Available at https://youtu.be/YYYfDCcCVHQ?si=gsyX1W8Iq_KggAFp.