This Is Your Pen on Music

Using Self-Notations to Investigate Free Improvisation

DOI: 10.32063/1102

Table of Contents

Clément Canonne

Clément Canonne is a CNRS senior researcher and the head of the Analysis of Musical Practices team at IRCAM. His research is mainly focused on collective musical performances, bringing perspectives from philosophy, ethnography and experimental psychology.

Nicolas Donin

Nicolas Donin is Professor and Chair of musicology at the University of Geneva. He has published extensively on the history of music and musicology since the late nineteenth century, with a focus on contemporary composition and performance, using methodologies from musicology and social sciences.

by Clément Canonne and Nicolas Donin

Music & Practice, Volume 11

Scientific

Introduction

Free improvisation is often presented as a musical practice in which improvisers aim at spontaneously creating music that is ‘as unprecedented as possible’,[1] without relying on pre-defined plans or pre-existing musical structures.[2] This emphasis on the ‘unprecedented’ should not imply that any instance of free improvisation is entirely deprived of many features traditionally associated with collective musical practices, such as deliberation, reflection, or structuring, be they oral or written. For example, free improvisers routinely spend time working or playing together in between concerts or recording sessions.[3] And while the goal of such working sessions is not necessarily to plan ahead the unfolding of the upcoming performance, nor to fine-tune instrumental gestures, they are often a time in which improvisers can reflect on their musical practice and explore new artistic directions, including via the production of various kinds of notational artefacts such as memos of instrumental techniques, graphic stimuli for performance, or rehearsal notes.[4] As a consequence, it is worth exploring free improvisation as a still uncharted territory of musical notation, one that improvisers are familiar with but would not think of as an integral part of their practice.

Over the course of two years (2018–2020), the authors of the present article invited members of the Umlaut collective – a group of expert musicians from the West European improvisation scene who have a strong background in jazz as well as contemporary and experimental musics – to participate in five workshops. Building on their curiosity and willingness to experiment with new musical rules and setups, we designed various experimental situations that explored the relation between improvisation and notation – notation being heuristically understood as any prompt for or representation of performance written on purpose by the musicians. This process of inquiry allowed us to try out and monitor several improvisational situations in which notation would serve as a tool to prompt, record, or recall a given performance. Once a variety of artistic and scientific situations had been tested behind closed doors, a final public presentation was organized (at IRCAM, on 10 January 2020).

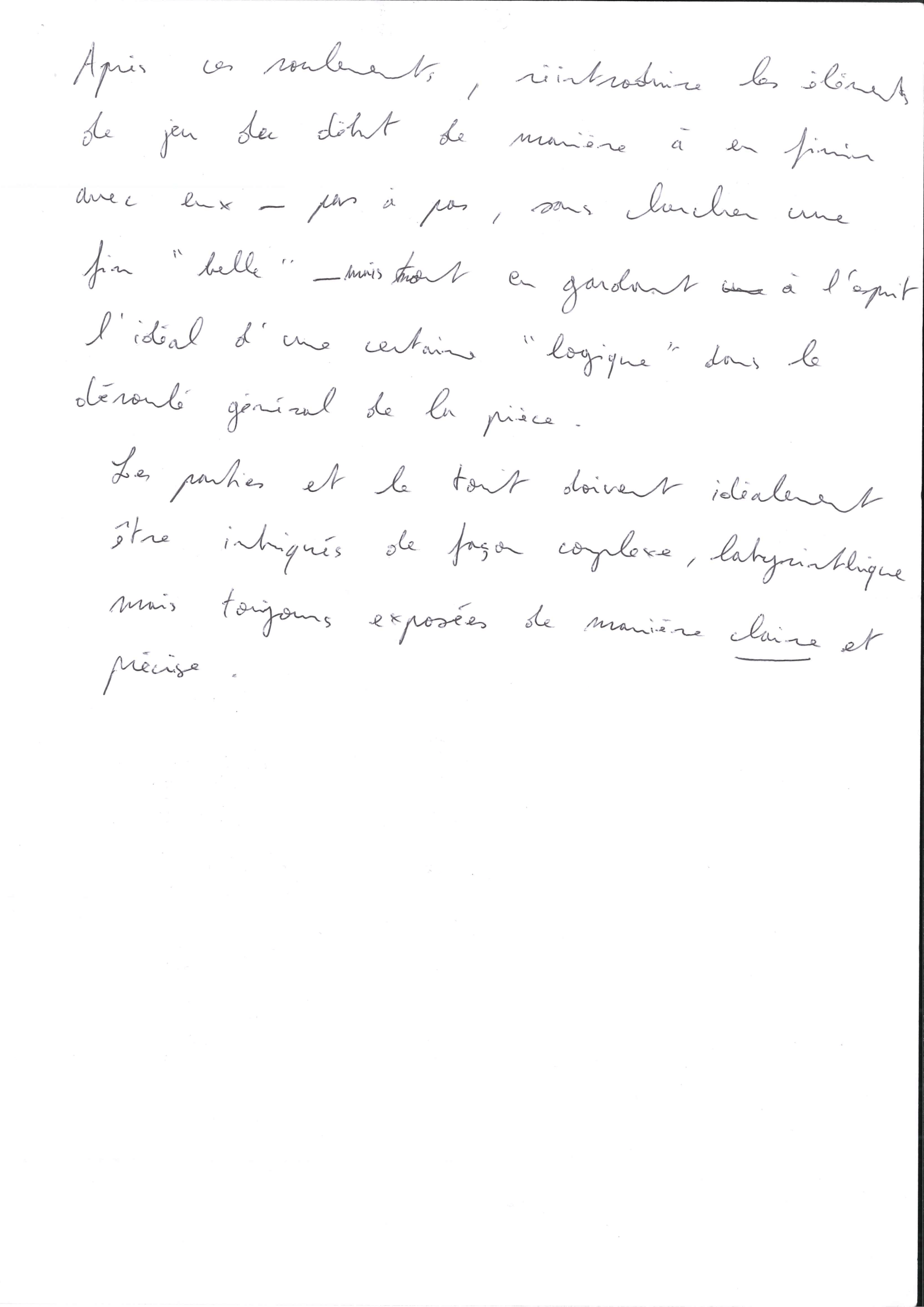

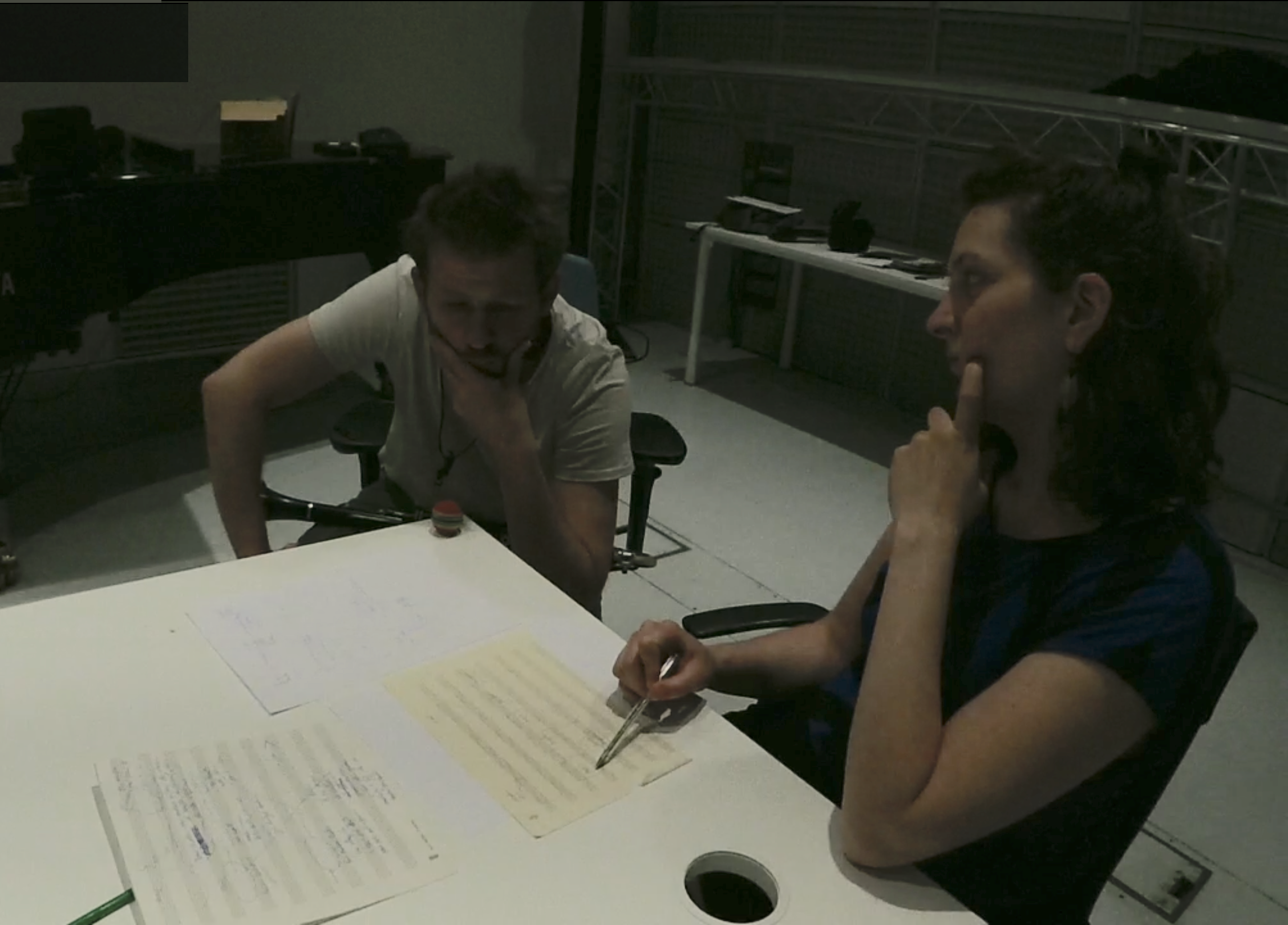

The five musicians involved were saxophonist Pierre-Antoine Badaroux, bassist Sébastien Beliah, percussionist Antonin Gerbal, pianist Eve Risser, and clarinettist Joris Rühl. Each closed-doors workshop took place in an IRCAM studio (as well as adjacent rooms for one-to-one interviews), lasted 3–4 hours, and was videotaped by two cameras (Figure 1). As we meant to chart the distinctiveness of each musician’s perspective on the music they play as a group, most situations also implied one-to-one interviews along with ensemble playing and reflection –whether the music was selected from twentieth-century experimental repertoire or their own output. A typical workshop would include two or three ‘sessions’ focusing on one experimental situation based on one specific musical piece or procedure. A typical session would include a series of individual and/or collective performances, alternated with individual and/or collective debriefings.

Figure 1 Risser, Gerbal, Badaroux, Rühl (from left to right) playing during the setup of the inaugural workshop (IRCAM, Studio 2, September 27, 2018). The observers and another camera are placed at the right of the frame. Beliah was not part of this session.

In this article, we will report on one such experimental situation that targeted more specifically the improvisers’ representations of the nature of the musical objects they manipulate through their performances. Philosophers have long been concerned with identifying the nature of musical objects.[5] The philosophical discussion is generally organized around two main debates: the fundamentalist debate (e.g., what kind of metaphysical objects – eternally existing types, sets of performances, etc. – are musical works from the common practice period?) and the identity debate (e.g., what are the properties that individuate musical works? Under what conditions can two musical works be considered to be the same?).[6] In general, these debates have been approached through abstract reasoning and involve far-fetched thought experiments and metaphysical paradoxes. However, recently, many philosophers have called for a more ‘descriptivist’ approach – trying to come up with theories that would best account for how musical objects are actually conceptualized and dealt with in a given musical practice.[7] Our experiment precisely aimed at making progress on that front, by investigating how improvisers think about the identity of their own improvisations – understood as both referent-free[8] and non-idiomatic[9] musical performances:[10] is there a sense in which two improvisations could be considered to be ‘the same’ to the eyes their performers? And if so, at which conditions two distinct performances could be considered to be versions of ‘the same’ improvisation?

On the one hand, within philosophical music ontology, numerous essays have been dedicated to the topic of improvisation, generally emphasizing the highly evanescent nature of musical improvisations.[11] In that perspective, improvisations are taken to be singular events, never to be repeated again. But this typically overlooks the possibility that more abstract building blocks might underlie these performances, and that these building blocks might be construed by improvisers as having some kind of ontological persistence, allowing re-identification from one improvisation to another. On the other hand, within the psychology of musical improvisation, several studies have investigated improvisers’ own representations, using either retrospective thinking-aloud procedures and post-hoc interviews[12] or sorting tasks.[13] But those two types of studies suffer from symmetrical limitations. Wilson and MacDonald and Pras and colleagues investigate in great detail how improvisers think about specific performances, but the thinking-aloud procedure is not immune to biases, notably post-hoc fabulations in which musicians would report what they believe to be true about improvisation rather than what they are actually doing.[14] As for Canonne and Aucouturier’s study, its goal was to elicit improvisers’ highly general and abstract mental models rather than the specific building blocks that might underlie a given performance.[15]

The experiment we report below was precisely an attempt to delineate an intermediate path – one that would allow us to shed light on the improvisers’ representations of their performances’ ontological structure (i.e., how they deal with notions such as similarity, persistence, and reproducibility when it comes to a specific improvisation) while avoiding the potential biases associated with post-hoc verbalizations.

Asking improvisers to note down their playing: Why and how?

As mentioned above, the experiment discussed here aimed to reveal improvisers’ representations of their performances’ ontological structure – what we will call their implicit ontologies. We focused on them performing their music with a high degree of freedom and had them use notation after the fact as a means to investigate the nature of what they had just played. Each musician went through three stages, shaped by the following process:

- Play a 2–3-minute solo.

- What would you note down in order to be able to play the same solo in the future?

- Please do so.

Our instructions and question were not presented in written form, nor were they known in advance – the next instruction or question would come only once the ongoing stage was completed. No other musician was allowed to enter the studio other than the one who was playing. On our request, the musicians agreed not to talk to one another for the whole session. The duration of the experiment was roughly 30 minutes. Every musician was provided with individual sheets of staved paper as well as blank paper. Data collection on self-notation took shape over the course of two different workshops.

We also extended this solo-centred experiment to duos in each of those two workshops. The performances were followed by two separate feedback interviews based on instruction 2). The musicians were then asked to come up with a joint notation of their duo performance (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Risser and Rühl discussing their respective notations of the improvised duet (IRCAM, studio 5, July 2, 2019).

Crucially, the two duos that were put together for this experiment had contrasting levels of familiarity. One of the duos consisted of Risser and Rühl who had been improvising together for the past ten years under the name ‘Duo Risser-Rühl’ and had spent many hours in rehearsing sessions to play and discuss ‘their’ music.[16] The other duo was made up of Badaroux and Beliah. While they have played with each other many times in different groups, they did not share such a joint history of improvising together in a duo setting.

As a result, we gathered the following takes – all of which are available here:

- Badaroux’s solo

- Beliah’s solo

- Gerbal’s solo

- Risser’s solo

- Rühl’s solo

- Badaroux-Beliah’s duo

- Risser-Rühl’s duo

A quick comparison between those performances and the recorded output of these improvisers would show that these performances were quite characteristic from the musicians with respect to style as well as playing attitude. While the 2–3-minute duration imposed by the experiment was unusual for them compared with their playing before an audience, the notion of playing under (and with) a specific constraint was not. Similarly, playing in an IRCAM studio as part of a research workshop was a first to all of them but playing in front of a handful of friends in an experimental setting was not. The place and format of these performances were neither routine nor essentially disturbing to them, and they expressed their interest in taking advantage of the specific demands of the project in order to experiment with their playing – as they would do on another residential workshop to set up a new performance project. In short, this workshop was the opportunity for a small departure from their usual business as much as it was a benefit to us as researchers.

On the same note, the status of our request for them to write down their solo may be seen as two-sided. On the one hand, all five musicians do master standard as well as alternative musical notations. On the other hand, improvisers usually don’t use notation this way, when they use it at all. Thus, our experiment was indeed deliberately challenging with respect to their culture and practice of improvisation, which are obviously not notation-centred. As such, it triggered significant responses from the musicians even before they put pen to paper. When we asked them what they would need to do in order to be able to play the same improvisation again, most of them requested a recording of their original performance so that they could listen back to it, and practice it until they could play it again. In other words, their first reaction was to construe the idea of ‘playing the same solo again’ as performing a sonic doppelganger, in the same way that Mostly Other People Do The Killing did in their famous album Blue by producing a sound-for-sound rendition of the improvisations that make up Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue, patiently learning and practicing from the original recording until they were able to perform a perfect duplicate – or something reasonably close to that. However, by forcing them to use musical notation rather than recording as a way to play the ‘same’ improvisation, we pushed them to come up with alternative identity criteria for their performance, besides mere sonic indiscernibility (i.e., the fact that two performances should sound exactly the same to be considered the same). Indeed, in selecting what to notate, the improvisers were prompted to identify the crucial elements that should be exemplified in order for the future performance to be an instance of that improvisation, and thus to make explicit the more stable abstract objects that underlie their original performances, beyond the transient nature of the musical sounds actually produced. In other words, preventing the musicians to have access to a recorded trace of their performance was a way to invite them to ‘abstract one step up’ – from the very specific sounds they actually played to, by force of circumstances, more indeterminate musical objects – and to reflect on modes of representation (i.e., how do they represent such or such aspect of their performance?) rather than on all the details contained within their performance. In that perspective, it is striking that the improvisers were not destabilized in the slightest once we told them they could not rely a recording: given that the musicians underwent our experiment right after playing, they all had a vivid enough memory of the improvisation they had just performed to commit its most essential aspects to notation. And that’s what our experiment was precisely after: identifying such essential aspects, beyond the more contingent elements present at the sonic surface.

We decided to call those documents ‘self-notations’ rather than ‘self-transcriptions’ because musicians could only rely on their memory, and they had to fix indexically the elements they would need, from their own perspective, to replay their improvisation. In that perspective, self-notation opens a window on the representations of the musicians involved – and in particular, how they deal with notions such as similarity, stability, and reproducibility in their own improvisational practice.

The very idea of asking these musicians what they would need to do (and to notate) to perform something that is somehow the ‘same’ as (or, at least, strongly similar to) a previous improvisation strongly clashes with popular views on improvisation which tend to construe it as a singular and evanescent event, intrinsically non-repeatable.[17] However, while it is true that free improvisers are likely to emphasize the singular and non-repeatable nature of their collective performances (for example because of the unpredictability of the interaction dynamics), it is much less the case when they talk about their solo performances. In other words, solo improvisations are widely considered as being of a very different nature than collective improvisations. This is discussed by Derek Bailey in his landmark book on improvisation. According to Bailey, solo and collective improvisation differ on two accounts: first, they differ in aesthetic terms (the former is generally more cohesive while the latter is more unpredictable); and second, they differ in normative terms (the latter is in fact ‘more exciting and more magical’ than the former, being closer to what is really at stake in improvisation).[18]

Free improvisers often concur with Bailey’s view. For example, saxophonist Marc Baron comments, ‘I wish I could say there was no difference between playing solo and playing with other people, but that’s not actually borne out by experience’.[19] Because musicians improvising solos have ‘all the space, but all the responsibility too’,[20] they often tend to prepare their performances in a much more deliberate way. As such, solo performances are typically described by free improvisers as entailing much more predetermination and control than their collective counterparts.[21]

Alternatively, free improvisers also emphasize that a solo improvisation is akin to the performance of an ‘internal’ composition that the musician has built over the years and that can be heard ‘as it is’, free of the unforeseen events that could emerge from the confrontation with other improvisers. In the words of John Butcher: ‘I think if you’re playing a solo concert you’re really being a composer. Certainly once you’ve done it a few times and you’ve got a history of some kinds of ideas.’[22]In that sense, solo improvisation can be seen as ‘a vehicle for self-expression, a way of presenting a personal music’.[23] Our five improvisers are no exception here: they all consider solo improvisation as a way to present their own musical personalities, and don’t hesitate to describe the elaboration of their solo works in terms of a compositional process.

Some of them have published a stabilized version of ‘their’ solo (or solos), such as Gerbal with respect to his 21-minute Sound of Drums, which he regularly performed under this title and released in 2016 as part of an all-solo CD. Even Rühl, who considers himself ‘not very much experienced in improvised solo’, is the author of a 17-minute piece called Toile (2018) relying on his long-term explorations of the technical subtleties of his instrument, which he published as a solo CD, together with shorter improvisations. Interestingly, Rühl ultimately released a written score for Toile, in which he tried to find ways to notate what had only been for long an oral composition, based on instrumental gestures patiently selected and memorized.

We thus had good reasons to believe that our improvisers would not be strongly unsettled when asked what to notate to be able to perform again the ‘same’ improvisation. However, how performers would react to our experiment in the duo case was much more difficult to anticipate. Given the differences between solo and collective improvisation highlighted above, and the higher degree of unpredictability typically attached to the latter, would they even be able to come up with a self-notation of their duo performances?

Five Approaches to Self-Notation

Let us present the tentative ‘scores’ produced by the musicians when asked to notate their improvisation just after the fact. Each of those is contained on a single page – on either blank paper, or staff paper. None of the musicians felt the need to give a title to their scores. By means of close reading of each score, we will contrast their respective types of notation and discuss the broader implications of their notational choices for reading and performance.

Sébastien Beliah’s Sequences

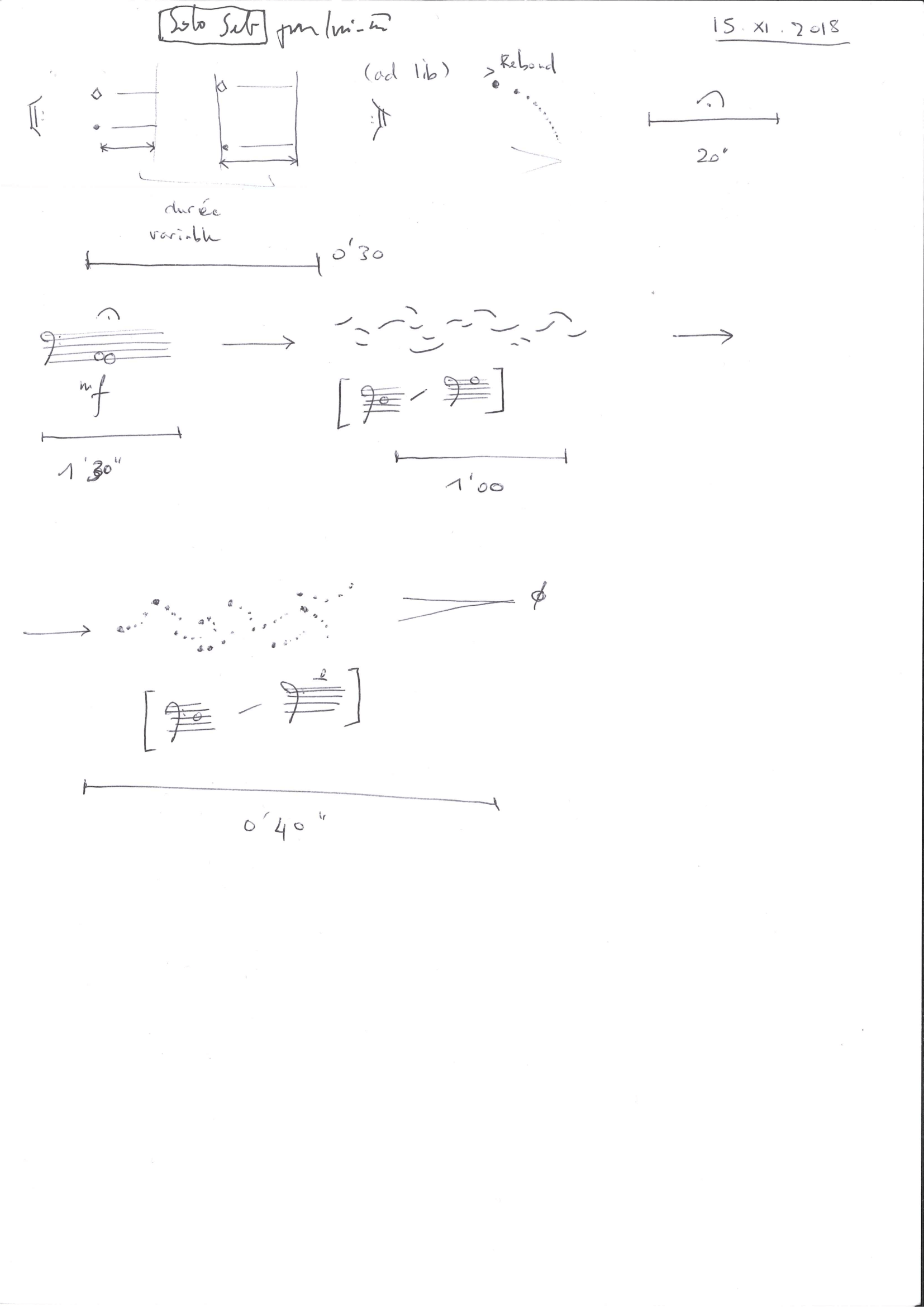

Beliah wrote down his improvised solo in the form of a series of short sequences, each one focusing on distinct bit of musical material (Figure 3). Though minimalistic in their writing, the sequences may last from 20 to 90 seconds (as specified in the time brackets placed under most of these). For the sake of clarity, we will call these as follows: Sequence 1 over the first system, Sequence 2 and 3 on the second system, Sequence 4 on the third and last system.

Sequence 1 consists of two tenuto sounds with harmonics which must be repeated ad libitum. The notation consists of a simplified tablature that distinguishes between the two sounds based on 1) the distance between natural pitch and harmonic pitch, and 2) their duration: the first sound is shorter than the second. This difference in length is not fixed, as suggested by the underlying verbal annotation (‘durée variable’). This sequence is completed with a ‘rebound’ (i.e. a gettato) notated by mimesis: a heavy dot reverberates into smaller dots following a descending curb that corresponds to a decrease of both pitch and dynamics. The sequence ends up with a 20-second silent fermata.

Each of the following sequences focuses on a single type of material, to be explored during a timeslot specified in length in the underlying bracket, and separated from the next one by an arrow. Arrows are very basic logical connectors that, in principle, do not imply any duration or phrasing in themselves. Here they might be understood first and foremost as tools of disambiguation: they make clear this is not an ‘open form’ musical piece, each line (system) must be read traditionally from left to right, up to down. They suggest a tight and smooth connection between sequences as opposed to the fermata.

Sequence 2 consists of a single major second interval, played mezzo forte. While during his performance, Beliah had played a smaller interval and explored its microtonal inflexions over frequent, audible bow changes, his notation paved the way for a diversity of renderings of a textural chord over a significant amount of time (1:30 of a 4:00 total, according to the values into brackets).

Sequences 3 and 4 offer schematic drawings evocative of two sound typologies. Firstly, short continuous gestures within the ambitus of a fifth, characterized by an internal curve toward higher or lower pitch. Secondly, discontinuous impacts following a global wave-inspired shape, within an octave, and decreasing a niente.

As a whole, Beliah’s score encapsulates western standard notation and quasi-conventional graphic notation within a fixed formal scheme, allowing for a potential reader to play a 4-minute solo made of a juxtaposition of sharply distinct sequences. Of all the self-notations, it is the closest to a fixed composition, leaving only the detail of texture realization to improvisation skills.

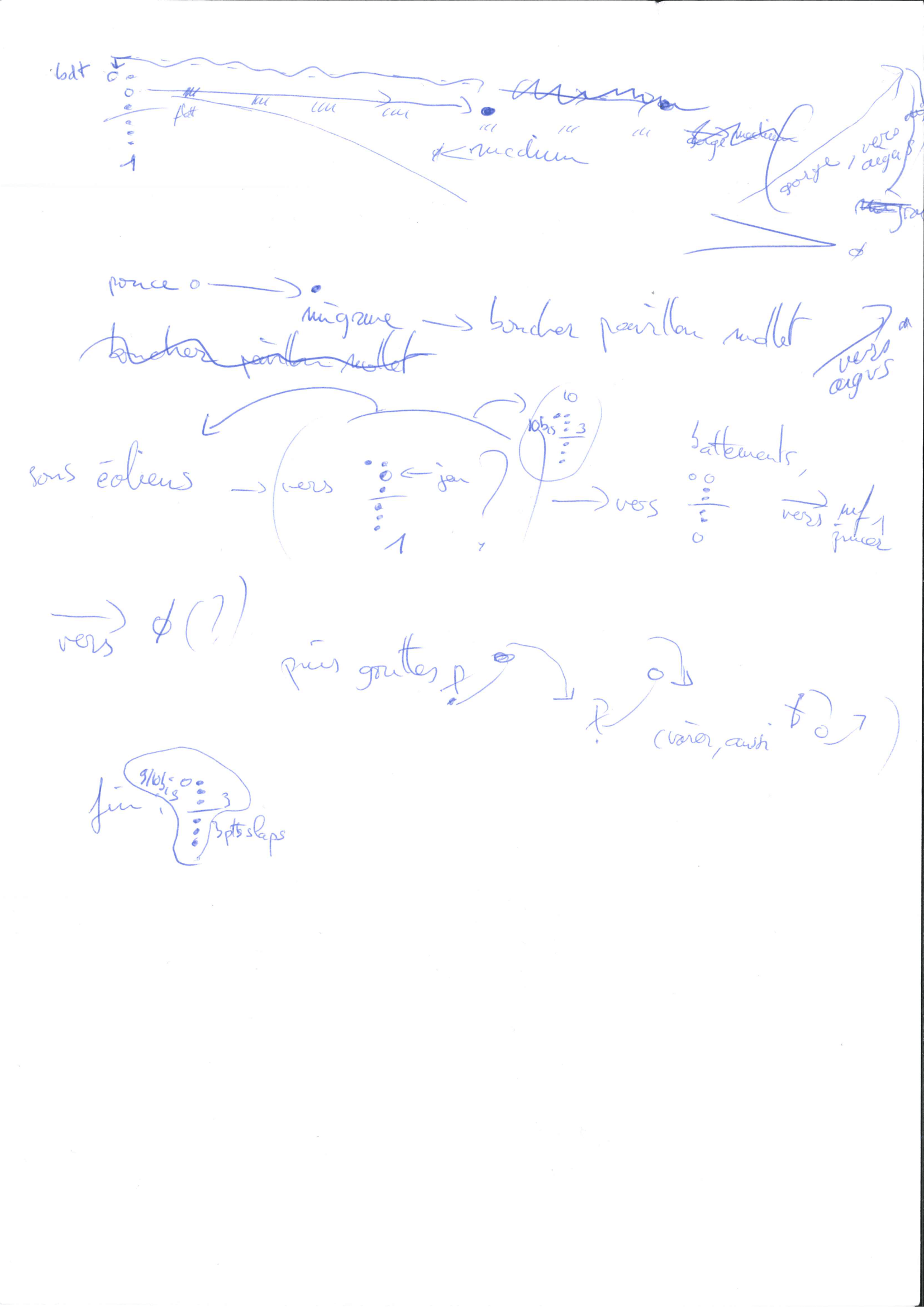

Joris Rühl’s Technical Pathway

Rühl also drafted a linear ‘score’ with a series of elements connected by arrows, but his notation is of a very different kind. It is first and foremost a tablature, weaving together fingerings and verbal notes (Figure 4). The piece may be described as a process of transformation of the initial sound through monoparametric alteration (gradual changes in dynamics, pitch, grain, timbre), followed by a sequence of variations on a small glissando gesture (see the notational variations of ‘drops’ (‘gouttes’), end of line 4). Fingerings, hence, are key elements of the identity of the piece: five of them punctuate the score, like stations to go through, including the initial and final sounds. Consequently, most arrows must be viewed as embodying the very process of transformation at the heart of the solo, as opposed to Beliah’s logical connectors devoid of any temporal consistency.

As for the verbal notes, they cover a diversity of functions. They may specify the playing technique, as in the following instances: ‘thumb’ (‘pouce’) and ‘obturate [the] bell [with the] calf’ (‘boucher pavillon mollet’) on line 2; ‘beats’ (‘battements’) on line 3; ‘three small slaps’ (‘3 p[e]t[i]ts slaps’). They may also come as a substitute to musical notation, as in the following instances: ‘low E’ (‘mi grave’) on line 2; ‘toward high register’ (‘vers aigus’), end of lines 1 and 2. Eventually, verbal notation may wrap up a type of sonic material that define one sequence as a whole, as in the final sequence in which schematic musical notation only develops for the reader Rühl’s idiosyncratic concept of ‘drops’ – actually, the written word would probably have been sufficient for him alone.

During our interview with Rühl just after his solo improvisation, he expressed some uneasiness at the prospect of notating or even memorizing it. He remarked that, had he known the experimental procedure in advance, he might have thought of a form and musical components he would like to explore (and therefore be able to recall and note down), but the solo in this case was different:

In instances like this one, it is often all about ‘situations’ that call for further ‘situations:’ because a given harmony comes up, I embark on it and feel that, if I remove this finger it will work, and now this other finger, and so on – there is a kind of technical response, an incentive to follow one pathway rather than another, and this is why it is difficult [to remember the solo after the fact]. There is no real formal intention. Except for the moment I decided to introduce a pause, or do the small notes – this I could reproduce quite faithfully.

As a result, his remembering process, and the subsequent notation, focused on the fingerings as well as those emerging properties of sound that resulted from its sustaining and variation. His approach to notation led to the scoring of a technical pathway that another expert clarinet player might be able to follow.

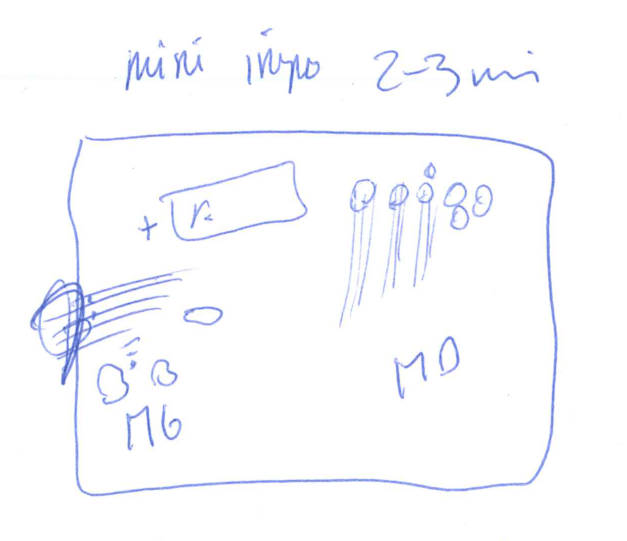

Ève Risser’s Instrumental Mapping

An elliptic diagram (Figure 5a) was the initial response by Risser to our request to write down whatever she’d need to be able to play the same solo in the future. This diagram essentially describes how she prepared the piano before playing the solo: on the left side, Blu Tack on strings around low B; on the right side, Blu Tack at the end of several strings in the high register; on the upper left side (small rectangle marked ‘+ r’.), an X-ray to play with at one point in performance. Risser later explained that this notation, in her eyes, was consistent enough with our demand: ‘The facts that the 2–3 minutes’ duration be written [on the top of the diagram] and that I’ve only this limited musical material imply I won’t go elsewhere while playing . . . Even if I were in another mood at the time of playing this again, I foreknow I would loop patterns, be quite repetitive [as in the original solo]’. As prefatory as it looked like, this rough piano map did actually embed most of her guidelines to re-do the solo.

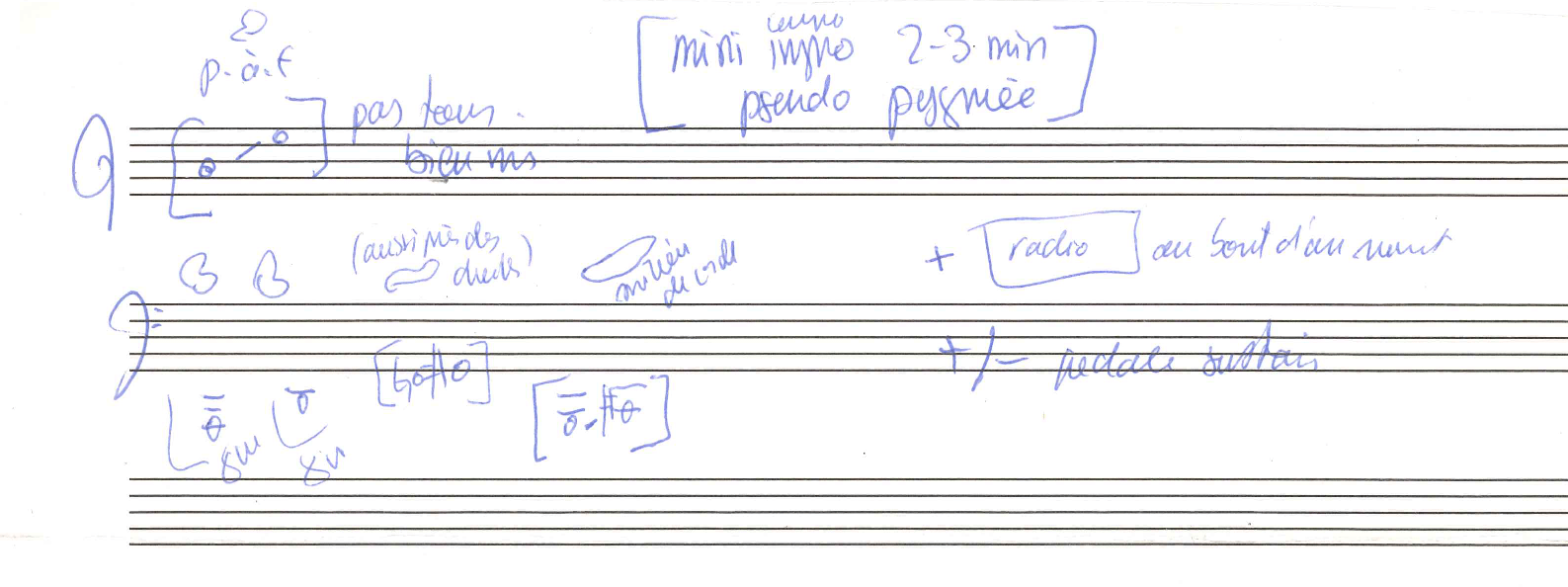

As she commented the diagram just after drawing it, Risser mentioned she should include the pitches played by each hand, to be even closer to what she had played. She went back to the piano, checked the pitches she had been using, and wrote them on staff paper. The resulting notation (Figure 5b), once completed with information from the initial prepared piano map, superseded it as the ‘score’ for the solo.

The preparation is now associated with specific pitches. On the side of the treble clef, Blu Tack (‘p.à.f’. refers to the French equivalent, Patafix) must be put irregularly on strings within the A4–E5 range (‘pas tous bien mis’ means ‘not all well placed’). On bass clef, A0 and D1 must be partially muted with bigger chunks of Blu Tack, while further Blu Tack must be applied to F2–G#2 (close to the pegs) as well as B1–C#2 (in the middle part of the strings). The use of square brackets for most of the pitches makes it clear that these must not be taken literally and might be replaced with neighbouring pitches. In the same spirit, there is no title for the solo, but a designation (in square brackets) as a 2–3-minute ‘mini improv’ or ‘mini composition’ in a ‘pygmy’-inspired style – which hints at a musical genealogy going from Aka polyphony (as known from the writings and recordings of ethnomusicologist Simha Arom in the 1970s) to the piano works of György Ligeti to their appropriation in jazz by twenty-first-century pianists such as Benoît Delbecq and Risser herself. Two complementary instructions are to be read on the right side of the page: ‘[insert] X-ray after a while’, and ‘more or less of sustain pedal’.

Risser’s ‘score’ outlines a mapping between instrumental limitations and pitch limitations. Taken together, these limitations define a specific zone for the improviser to work with. In the present case, due to the brevity of the solo as well as its stylistic connotation, Risser considered it improbable that she would end up with anything significantly different from her initial solo, were she to play the solo from this notation and without listening to the recording. Conversely, another reader would have to be familiar with her highly idiosyncratic playing and musical culture to make sense of this small set of constraints.

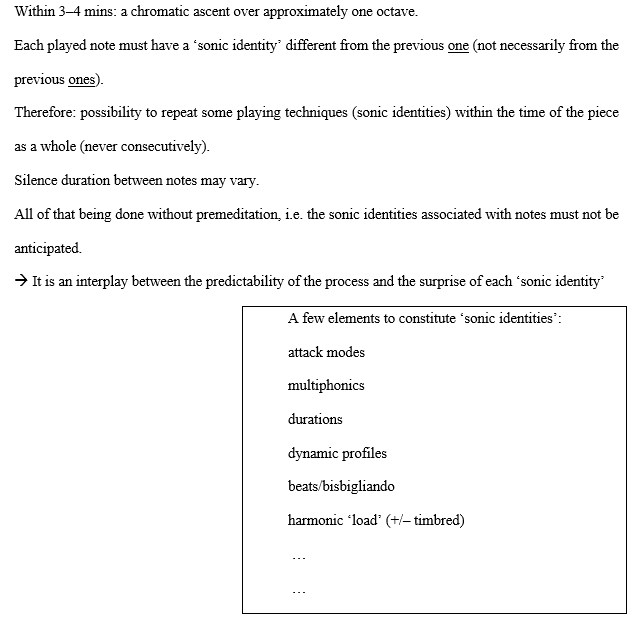

Pierre-Antoine Badaroux’ Protocol

Saxophone player Pierre-Antoine Badaroux offered the following text (see Figure 6) as a score for his solo:

This list of instructions puts forward both an overarching concept (‘a chromatic ascent over approximately one octave’) valid for the entire duration of the piece, and a small set of rules that allow the player to specify their sonic material locally.

The list also includes two instructions with respect to the process of production: on the one hand, a requirement that the sonic material not be prepared in advance; on the other hand, an open-ended list of suggestions for the parameters and types of sound to be used. Taken together, these instructions guarantee that performing this piece should include a measure of improvisation, as opposed to a mere recipe that would allow the performer to fix their own realization of the piece in writing.

Eventually, Badaroux’s text adds a synthetic self-commentary on the solo (introduced by a short, QED arrow), that may be understood either as a listening guide, or a clue about the ‘feel’ of the piece directed toward the performer. At the bottom line of the protocol is the framing of its perception and interpretation.

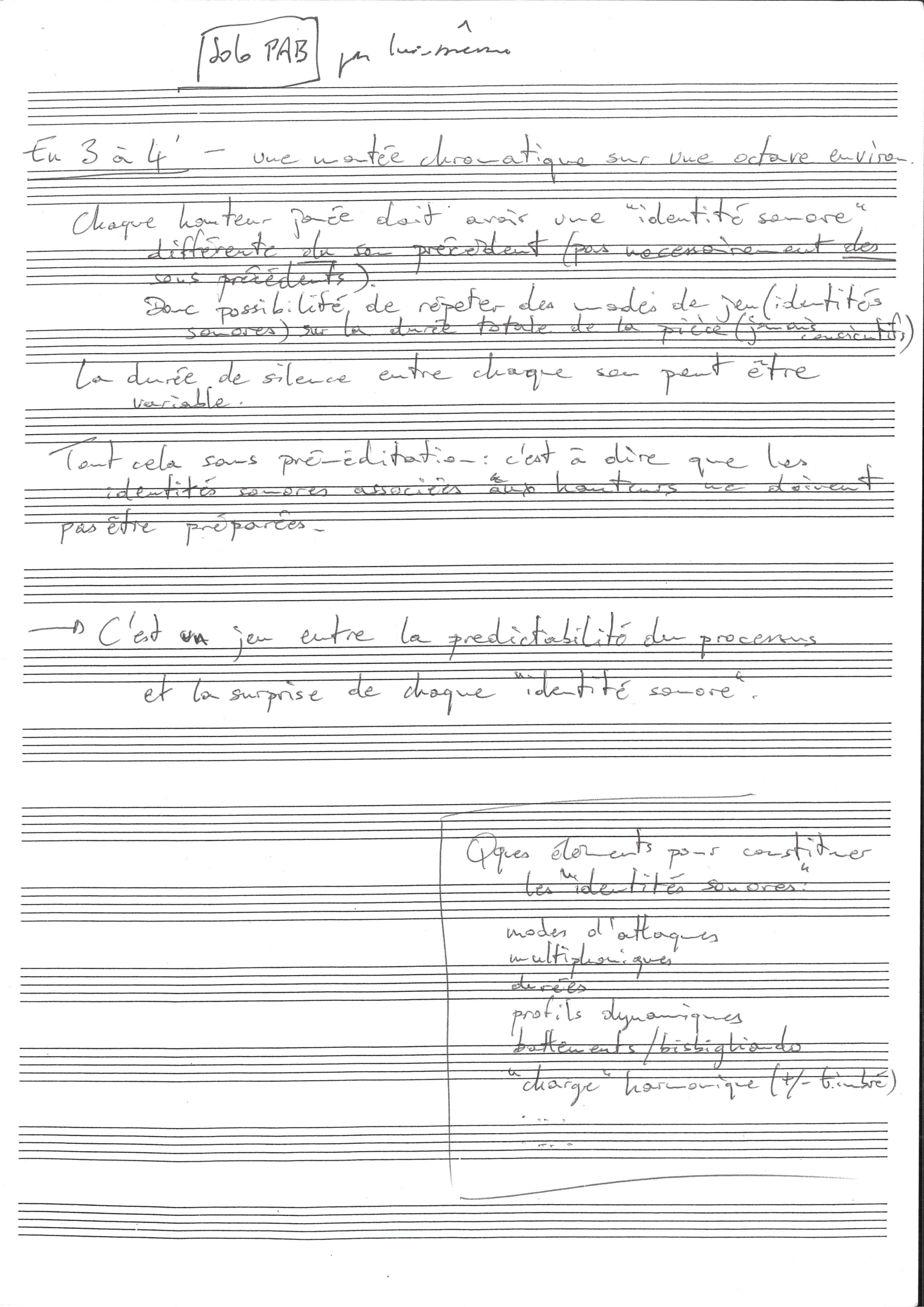

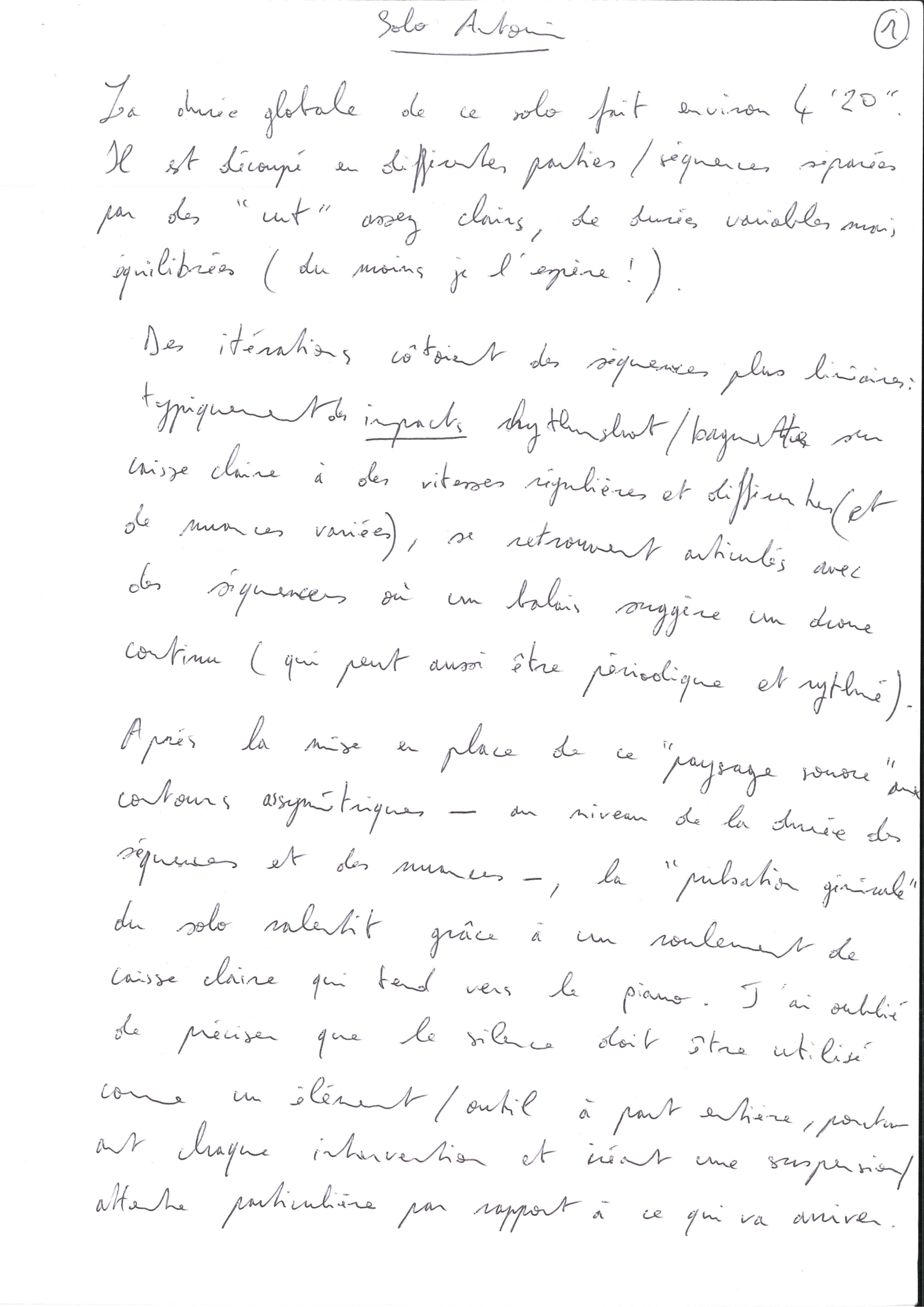

Antonin Gerbal’s Stylistic Tutorial

Compared to Badaroux’s protocol, percussionist Antonin Gerbal wrote out a substantial text characterized by fully fledged sentences, a narrativist description of the musical form, and two appearances of the author’s voice using the first person singular (Figure 7). Entitled ‘Solo Antonin’, the text reads as follows:

The overall duration of this solo is about 4:20. It is divided into different parts/sequences, separated by quite clear cuts. Their durations are variable, but balanced (at least I hope so!).

Iterations neighbour more linear sequences: typically, rimshot/drumstick impacts on snare drum at distinct, regular speeds (and varied nuances), are articulated with sequences in which a brush hints at a continued drone (which may also be periodical and rhythmic).

Once this ‘soundscape’ of asymmetrical contours (with respect to duration of sequences as well as nuances) is installed, the ‘global pulse’ of the solo slows down by means of a snare drum roll leaning toward piano. I forgot to mention that silence must be used as an element/a tool on its own, punctuating every intervention and creating special suspension/expectation towards what comes next.

After those snare drum rolls, put back in play the initial elements so as to get done with them – step by step, without looking for a ‘beautiful’ end – but keeping in mind the ideal of a certain ‘logic’ in the general unfolding of the piece.

The parts and the whole must ideally be intertwined in a complex, labyrinthine way, but always exposed in a clear and precise manner.

According to this text, Gerbal’s solo is instrument-specific, like the ones by Rühl and Risser but unlike Badaroux’s (Beliah’s being somewhere in the middle in this respect). However, the more it goes, the more it stresses stylistic and aesthetic properties that might be achieved through different means – it ends up telling more about what should be perceived, than how to produce it. There is indeed a significant oscillation between description and prescription in this text. When the durations are characterized as ‘variable, but balanced’, the narrative voice adds an interjection as facetious as humble (‘at least I hope so!’) that only makes sense as a description by Gerbal of his actual way of performing the solo. On the contrary, some sentences distinctively articulate prescriptions for anyone who would like to perform the solo (for example, ‘put back in play the initial elements so as to get done with them’).

One might read this verbal score as a tutorial to a fellow percussionist by a performer well versed in this particular solo, handing it over to him based on his memory or video documentation of his own playing. By means of this advising tone, Gerbal hints at stylistic features of the solo (from the iterative/linear dialectics to the role of silence to the control of ‘global pulse’ through dynamics), and uncover a deeper layer of intentionality in the final draft of his poetics (be true to logic over superficial beauty, be clear and precise while navigating complexity).

A Foray into a Rich Notational Culture

To perform the self-notation task, each musician tapped into different zones of a broad notational culture characteristic of contemporary free improvisers,[24] encompassing standard western musical writing, experimental music, and popular music charts and tabs.

Badaroux relied on verbal instructions, in line with experimental music and conceptual art from the 50s and 60s (Yoko Ono, La Monte Young, John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen, etc.) and their posterity in the later work of Cornelius Cardew, Christian Wolff, Philip Corner, and Malcolm Goldstein among others. Ambiguity and paradox within instructions are a frequent feature of verbal scores in this tradition,[25] and a notable fixture of Corner’s scores throughout all his career, scores researched in-depth by Badaroux for an ambitious recording project involving most of the other participants in this workshop.[26] In contrast with that approach to notation, Badaroux’s text set up perfectly applicable rules and eliminated as much fuzziness and contradiction as possible while maintaining a good measure of indeterminacy.

Rühl relied on instrumental tablature. Though historically associated with string instruments, tablature has been a crucial component of the dissemination of novel, ‘extended’ playing techniques in new music since the 1960s, and this is particularly true with regard to wind instruments. As Rühl’s timbral exploration relies mainly on subtle variations of breath, mute, and fingerings, his notation firmly followed on the precedent.

Beliah drew on several aspects of current common practice of notation in experimental music, i.e., a blend of western standard notation, graphic notation, and tablature, all framed by the centuries-old western concept of score reading as consistent with prose reading (from left to right and top to bottom). Pitch may be determined by tablature, staff notation, or drawings correlated to a given register in staff notation. Temporal unfolding is fixed by a duration expressed in clock time for each sequence, with no further rhythm or tempo markings. Dynamics appear in abbreviation (mf) as well as signs consistent with standard notation – as are da capo and accent marks.

Due to her preparation of the piano, Risser’s notation was rooted in the specifics of this ad hoc nomenclature. Over the years, Risser has indeed developed an idiosyncratic notational system, each object used in her preparation set being encoded by a pictogram. Looking at her notebooks, one can see that these pictograms are used in many different ways: to quickly notate a specific preparation that came up during improvisation, to compose new music, but also to explore various ways of combining or categorizing her objects.[27] Each of these pictograms encapsulates meaningful information well beyond the object it is referring to. Notation thus appears here as a tool to trigger her memory (of situations) and action (the various performing gestures associated with such or such object).

Finally, Gerbal’s stylistic tutorial, though pertaining to the category of verbal scores, has a reflective, almost essayistic tone that can be related to work descriptions in public musicology. If Risser’s notation owes to those nomenclatures and performer instructions that are usually found at the front of musical scores, Gerbal’s notation is indebted to the programme note that some composers offer as an accompanying text, weaving together technical insights of the creative process and aesthetic claims, and often intended as listening guides.

Overall, the self-notations reflected the notational systems with which the improvisers are most familiar, or, at least, the ones they tend to use when they need to note down their music. But beyond a mere familiarity with a notational system, the self-notations also reflect various ways to think about what it is to improvise a solo: exploring a situation, building a form, following a set of internal rules, interacting with one’s instrument, or being true to one’s own artistic persona. In the Discussion section, we examine in more detail the ontological implications of these various conceptions.

The aporias of duo’s self-notations

We also subjected our participants to a variant of our experiment in which they had to improvise a short duo performance and then try to jointly come up with a notation in order to actually play the ‘same’ duo again.

As could be expected, all the musicians insisted on the increased difficulty of having to notate the elements they would need to be able to perform again the ‘same’ duet, compared to the solo condition. However, the two duos ultimately reacted in a dramatically different fashion: while the Risser/Rühl duo managed, after many exchanges between the two musicians, to produce a joint document that could support the re-enactment of their original performance, the same exchanges between Badaroux and Beliah led the two musicians to renounce to the production of such a document, pointing out the incompatibility between the very idea of trying to ‘play again the same improvisation’ and the situation of collective improvisation.

Badaroux/Beliah: self-notation and the essence of collective free improvisation

Neither Badaroux nor Beliah had any trouble identifying the main characteristics of the performance they had just improvised. In their individual debriefings of the performance, not only did they discuss the same musical parameters, but they did so in surprisingly similar terms: the interaction between the two musicians is described as ‘convergent’ (Beliah) or ‘congruent’ (Badaroux), the musical materials used as ‘complex’ (Beliah), ‘granular’ (Badaroux), and the overall form as divided into three parts, with a ‘progressive sonic rarefaction’ (Badaroux). It is thus not because they did not agree on such defining properties that the musicians did not manage to produce a self-notation of their performance. The reasons went deeper: the musicians felt that, if they were to fix these different properties in notated form, then the re-enactment of this notation would lose its improvisatory status. Importantly, such concern was never raised when they had to imagine the notation that would allow them to play again the same solo improvisation. This difference between the ‘solo’ and the ‘duo’ conditions of our experiment in how ‘playing the same thing’ interacted with the very idea of improvisation is striking.

For the Badaroux/Beliah duo, the essence of the improvisation seems to precisely lie in the moment-to-moment decisions and implicit negotiations musicians have to make regarding the temporal unfolding of the performance: playing a piece in which such temporal unfolding is planned in advance would thus inevitably result in something else than improvisation.

For Badaroux and Beliah, while solo improvisation could accommodate the idea of playing the ‘same’ thing and still preserving at least part of the improvisatory status of the original performance, and of the aesthetic qualities associated with it (unpredictability, presence, etc.), this turned out to be simply inconceivable in the duo case.

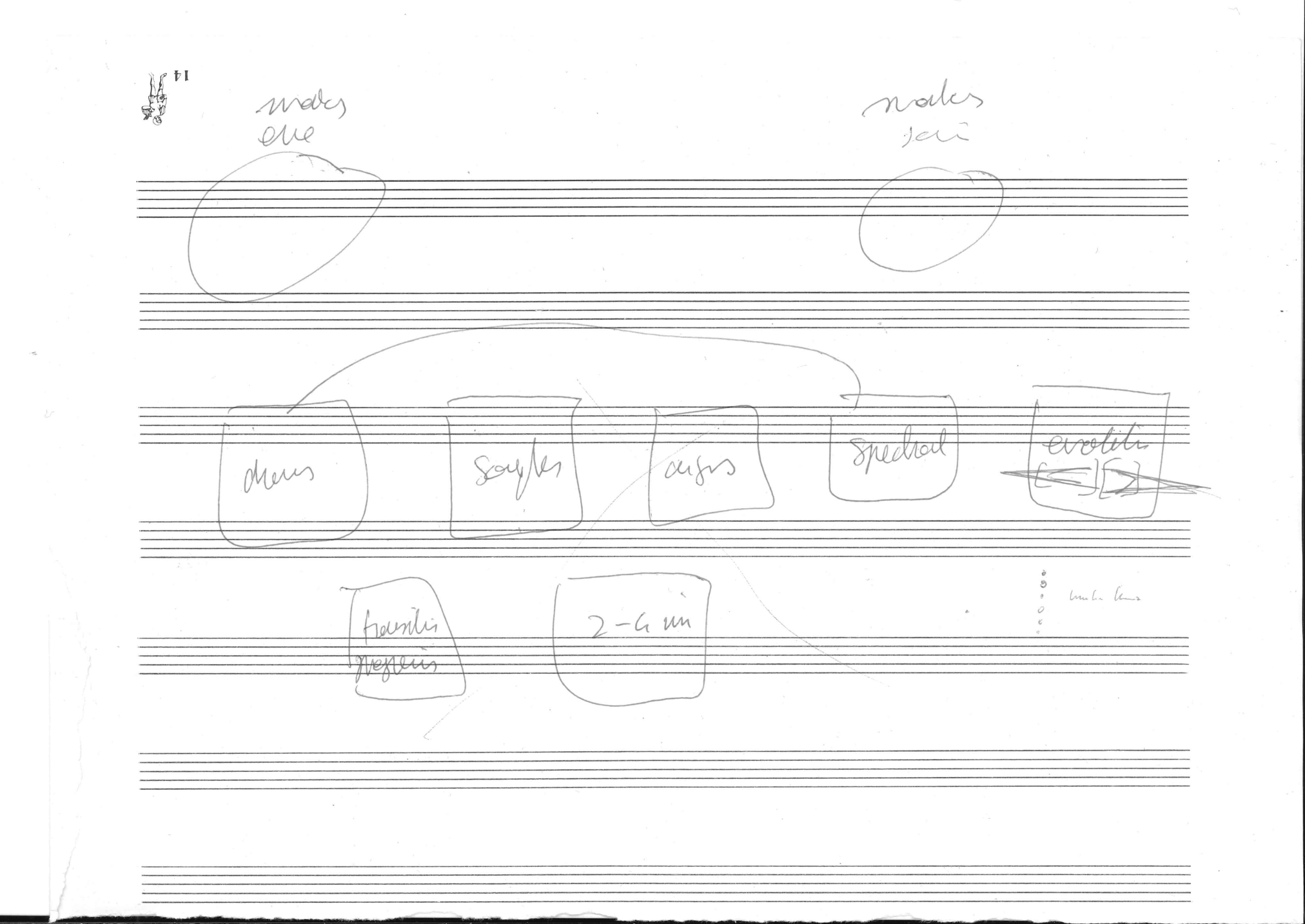

Risser/Rühl: self-notation and the identification of shared modules

Figure 8 shows the self-notation Risser and Rühl ultimately produced. Here, it is important to notice that the musicians precisely made the choice of not fixing any kind of temporal arrangement in their self-notation. The process that led to this choice deserves some unpacking. Interestingly, Risser started by notating a sequence of musical situations (with arrows between each situation representing the process of going from one situation to the other) before changing her mind and suggesting a notation with different ‘modules’ (‘drones’, ‘breath sounds’, ‘high-pitched sounds’, ‘spectral’, etc.) that could be played in any order (and not necessarily in an exhaustive way), with ‘progressive transitions’ between one another:

The first version gave the order in which we’re supposed to play the situations, it’s more complicated. But we are improvising: if we know that we must develop something, then … I prefer not to fix the points where we switch, because if I say exactly where it is and it’s not in the right place when we’re playing again, then it’s likely to get very complicated and eventually screw up. I thought that what I like is to figure out how to have something evolve and change in an organic way … notating the overall principle rather than the precise unfolding.

The exchanges the two musicians had regarding whether they should notate a given sequence of events and/or musical situations reflect a similar concern:

JR: It’s the temporality that’s super hard to redo …

ER: Is the idea to play again the same form? For me, what’s important is to provoke the same state, to remain organic. I don’t really care about the original sequence. But we could try to stick to it with 2, 3 poles …

JR: It’s all about transitions, developments. That’s what’s complicated: forcing the performance into a pre-planned development …

ER: That’s what I want to avoid!

JR: There you go. But then, what improvisation allows is that if it goes that way, well, you go there; and if ‘that way’ is something we didn’t write in the score, well, do we go there? That’s the question …

ER: No, but I think we’ve got plenty of material [notated] to restrict ourselves.

Once they decided to leave the temporal unfolding open, playing the ‘same’ duet was thus mainly a matter of using the same kind of material within the same time format (2–4 minutes):

ER: For me, our duet is characterized by the fact that drones were systematically spectral, that there were some breath sounds going into them, and that there is a high-pitched passage. It’s also pretty short, huh? And that there are some dynamic evolutions, but it doesn’t go in all directions at once.

JR: As for myself, I’m very attached to the technical stuff: I know I made those sounds and that’s what characterizes this piece rather than another. There’s also the fact that it’s short. I think that influences the length of the sequences: so you’re right, it doesn’t go in all directions at once, but maybe we’ve evolved a little faster than when know that we’re going to play for 40 minutes.

Still, it is striking that, once the issue of the temporal unfolding was put aside (on which they shared similar concerns to the ones expressed by Badaroux and Beliah), the Risser/Rühl duo didn’t resist the idea of repeating the same collective improvisation as much as the Badaroux/Beliah duo did, and they thus engaged in finding a notation that could support this endeavour. We come back to the factors that might explain this difference in the discussion below.

Discussion

Different Grains of Sameness

At first glance, there seems to be a wide variety amongst our five improvisers in the quantity of information they considered to be necessary to preserve in order be able to play the ‘same’ solo at a later time. Their self-notations indeed oscillated between very ‘thick’ descriptions of their performance and very ‘thin’ ones (Davies 2001). While these differences could simply reflect whether or not improvisers had a precise memory of their performances, we suspect that they in fact reveal that the notion of ‘sameness’ is understood very differently amongst our improvisers – indeed, in the verbal commentary she made when commenting on her self-annotation, Risser in fact demonstrated that she remembered precisely the first moments of her performance: ‘Right at the beginning, I realized that I didn’t put the Blu Tack correctly, it lowered the pitch, I was really surprised’. Her notation thus included very precise details on how and where to put the Blu Tack. In other words, her self-notation revealed that the temporal unfolding of the events on a short time scale was seen as much less relevant to the identity of her improvisation than the timbral constraints implied by the instrumental preparations.

Differences in self-notations are also present at a smaller scale, the musical and instrumental elements that comprise each improviser’s vocabulary being described with various degrees of determination. Some elements seem to be well-defined, as is attested by the precision with which they are notated in order to be ‘played again’. Other elements are identified in a much looser way, and thus translate in more indeterminate notations, reflecting that there could be many possible ways to realize them. This oscillation between different levels of determination in the notation is particularly clear in Beliah’s self-notation, which alternates between more or less determinate modes of notation to describe the different elements of vocabulary used in his performance. Again, his verbal commentary shows that it is not a mere matter of having trouble to remember some elements. Some elements of the improvisation are indeed presented as being intrinsically variable:

Some things are relatively precise but some things [aren’t] . . . in fact I would have to try to formulate some of the materials that I play . . . for example, for this passage, I would say that I play some kind of melismas in pizz, with a relatively variable density [Beliah, describing what he would need to notate to be able to play again the same improvisation].

However, one should probably not take the precision of the notation used by each improviser as strictly equivalent to the degree of determination they ascribe to the elements which underpin their solo performances. For example, a simple indication of instrumental preparation can entail much information about what to do and how to play with it:

I have the impression that the sounds that are placed inside the piano all induce a given character. When I put a preparation in the strings, it almost means how I play it. I don’t play a given preparation in 1001 different ways because, usually, I find that it sounds good when played in a certain dynamic, at least in my internal composition [Risser, commenting on her own self-notation].

Conversely, something can be notated very precisely while in fact denoting a much broader class of possible realizations. For instance, Beliah notated the ‘kind of drone’ he did in the middle of the improvisation with two pitches that are not the ones he actually used in his performance, suggesting that such drone could be indifferently realized with different low pitches while retaining its overall identity.

But even if there is no one-to-one relationship between the degree of determination used in the notation and the degree of stability they confer to the many elements that comprise their solo performances, our experiment still allowed us to identify the different layers of their implicit ontologies. Three levels can be identified here.

At the more global level, there is the individual musical territory, the broad stylistic and aesthetic principles that will be exemplified in one way or another in each of their solo performances. For example, in the extract above, Badaroux characterizes his musical territory as the exploration of ‘the relationship between the discrete and the continuous;’ and this general description clearly reflects in the way he summarized his solo in the self-notation he delivered for us. Similarly, Gerbal speaks of his solo as rather ‘traditional’ music: ‘I didn’t reinvent the wheel this morning compared to what I’m used to doing’. And again, in his self-notation, the broad principles that characterize his musical territory are clearly presented: ‘Iterations neighbour more linear sequences;’ ‘silence must be used as an element/a tool on its own, punctuating every intervention;’ or lastly, ‘the parts and the whole must ideally be intertwined in a complex, labyrinthine way, but always exposed in a clear and precise manner’. Finally, when describing her solo music, Risser points out that ‘I’m always building these solos with stuff that comes back. It allows me to make static music. If I change my mind all the time, I feel like I’m in a narrative mode, and I’m less interested in it.’ And sure enough, when commenting on her self-notation, she explained that, even if the hypothetical second improvisation that would follow the one she did for our experiment were ‘a bit different’, she still ‘knew that there would be many loops, quite repetitive’.

At the intermediate level, there are the more or less stable musical situations – that comprise their solo performances. Whenever they are playing, the musicians typically pass through a series of more or less discrete ‘areas’ or ‘modules’, each with their own identity.[28] In the case of pianist Risser, the Aka-inspired sequence – is clearly one of these ‘areas’, and as such can be easily invoked and remembered with only limited information. Those situations are defined at a less abstract level than the musical territory. For example, following up on Risser’s ‘pygmy’ style sequence, it is not only about doing ‘static, non-narrative music’, with ‘stuff that comes back;’ it is also characterized by a specific piano preparation, a percussive use of the left hand and short looped motives in the right hand. Similarly, the ‘piece’ performed by Badaroux is not about the specific pitches or instrumental techniques used in the performance, but about a certain way to perform a chromatic scale:

The first idea, I think, is the idea of a sort of chromatic scale. In fact, I think I could limit myself to this idea of a chromatic scale, which starts here and arrives there, and with the idea that each chromatic pitch is played with a different technique, so either a type of multiphonic, or beats, or different durations, or different dynamics, and so on. And for me, if I did that again, even if it’s not exactly the same pitches or the same techniques, it would be the same piece, the same solo [Badaroux commenting on his self-notation].

Finally, at the local level, there are the musical materials and elements of vocabularies that the improvisers use in their solo performances and that have their own degree of stability. In that sense, playing the ‘same’ improvisation can also be a matter of playing the same materials with a given duration and a given temporal arrangement. When we asked Beliah what he would need to notate to play again the ‘same’ improvisation, he told us that he ‘would note a form with durations, and inside, materials . . . cause I sure as hell couldn’t do it over again. But then, I would try to give myself the information about the materials I’ve played that would allow me to make something as close to it as possible.’ Similarly, for Rühl, playing the same improvisation is essentially about remembering the materials he used: ‘I was about to say that I would need the fingerings that I used, but clearly, it would be difficult for me to remember exactly’.

Beyond the identification of the three ontological layers that make up our improvisers’ implicit ontology, two additional remarks can be made. First, improvisers have different ways of organizing the ontological space presented above. If all three layers are always present in some way or another, they do not necessarily have the same importance for each improviser. Here, our experiment allowed us to investigate at which layer(s) the notions of sameness, identity, and stability were more relevant for them: at the broader level of the territory, at the intermediate level of the situations, or at the smaller level of the materials. For some of our improvisers, playing the ‘same’ improvisation is mainly a matter of sampling again their musical territory, and this led them to focus their self-notation on the description of such territory, as did Gerbal. For others, playing the ‘same’ improvisation is mainly a matter of reinstantiating a given musical situation, and this led them to focus their self-notation on the description of the crucial properties of such musical situation, as did Badaroux and Risser. For others, finally, playing the ‘same’ improvisation is mainly a matter of preserving a given temporal arrangement of musical materials, and this led them to focus their self-notation on the description of such materials, as did Beliah and Rühl.

Second, and more importantly, how the improvisers think about what it is to play ‘the same thing’ on a given level is highly constrained by how the higher levels are defined, and by the importance the improvisers ascribe to those higher levels. This aspect is particularly clear when considering the implicit criteria improvisers used to preserve the identity of the materials they played in their initial performance. For Risser, the materials she played are highly dependent on the musical situation she was exploring: she thus tolerated a high degree of variability in the way to present such materials, as long as it preserved the identity of the situation (i.e., the ‘pygmy’-inspired situation). For Rühl, the materials are not articulated to a given musical situation but to his musical territory as a whole, construed as a ‘poetry of technique’ (to borrow the liner notes of his solo recording, Toile Étoiles), a highly perilous exploration that seeks continuous interpolation between some of the most fragile sounds of the instrument: as such, the identity conditions of the materials used in his performance are very strict (as attested by the precision with which he tries to describe them in his self-notation), each material needing to stay the same to maintain the acoustic connection that exist from one sound to the other and thus to preserve the logics that underlie his whole musical territory. The materials are thus both central in his implicit ontology and at the same time highly constrained by how he conceives of the musical territory of his solo performances. Conversely, the identity of the materials explored by Beliah can endure significant variations (and are thus notated in a much looser way) because they are neither strongly associated with a characteristic musical context, nor with a sharply defined stylistic or aesthetic territory. As such, it is the materials themselves that play the role of musical situations, triggering their own instrumental explorations, and they retain their identity as long as they trigger the same kind of instrumental exploration.

The implicit ontology of our improvisers is thus a good example of what Nemesio García‐Carril Puy describes as a nested ontology: when performing solo, free improvisers instantiate musical objects of increasing degrees of abstractness, and they think of those objects as having some kind of stability or permanence from one performance to the other.[29] Our experiment pushed them to make explicit the criteria they would use to decide that two performances are similar enough to be seen as two versions of the same improvisation, and to spell out the conditions at which they would consider that the identity of the various musical objects that underpin their solo performances is preserved from one improvisation to the other. To be sure, in a sense, free improvisers never play twice the same thing; but while performing, they are also navigating a complex ontological space, one populated with objects of various degrees of stability. In that perspective, our experiment can be seen as a first step in the mapping of those complex spaces.

Familiarity and Sameness in Collective Improvisations

A second point worthy of discussion is the striking differences we observed between the Badaroux/Beliah duo and the Risser/Rühl duo in how they reacted to our self-notation protocol. The reason for this is probably to be found in the existence of a shared musical territory in the case of the Risser/Rühl duo, which results from their history of playing together. This effect of familiarity on the creative process of improvisers is in line with results from previous studies which have showed that musicians familiar with one another shared mental models of free improvisation[30] and ended up improvising performances that were more and more prototypical of their group identity.[31] In other words, in the case of the Risser/Rühl duo, because of the familiarity between the two musicians, the materials, situations and relations explored by the musicians (such as ‘spectral drones’) somehow pre-exist the performance and are not highly dependent on the duo’s interactional dynamics in the moment. Hence, it could make sense for the musicians to notate such elements independently from the precise temporal path actually taken during the performance.

On the contrary, in the case of the Badaroux/Beliah duo, materials and situations are much more dependent on the interactional dynamics. In a sense, they emerged through such interactional dynamics. For example, the beginning of their duo performance, which presents a mixture of granular elements, is clearly described by Sébastien Beliah as the result of a serendipitous discovery:

the beginning of the performance was funny, because we almost [fell on the same material] by chance, so it’s true that it guided the whole performance. But why not? If you’re lucky, why deprive yourself of it?

In other words, the whole interactional attitude the musicians adopted towards each other and the kind of materials they used throughout the performance were the result of the precise way they began the improvisation. Hence, given such dependency, it made no real sense for the musicians to notate those elements independently of the duo’s precise interactional and temporal dynamics.

Subjecting duos to our self-notation experiment allowed us to highlight two important aspects of collective improvisation. First, there is an ineliminable difference in nature between solo and collective improvisation which lies in the way musicians deal with the temporal unfolding of the performance: while planning ahead such unfolding is largely compatible with solo improvisation (as attested by the fact that all our improvisers did actually specify the overall temporal organization in the self-notation of their solo performance), it appears to be antithetical with the idea of collective improvisation, because it is precisely in the interactive negotiation of such unfolding that the essence of collective improvisation seems to lie, at least for these improvisers. Second, the relation between, on the one hand, materials and situations, and the interactional dynamics of the improvisers on the other, seems to be largely dependent on the familiarity that exists between the musicians: the more the musicians are familiar with each other, the more likely they are to have built over the years a shared territory that allow them to refer to the different components of their individual territories in a quasi-autonomous way, independently of the way those components are actually brought into play through the interactional dynamics.

Conclusion

To conclude, we would like to highlight some broader implications of our exploratory setup. First, it was a place of emergence: the musicians’ eagerness to playfully experiment at the margins of their own knowledge and practice made it possible for us to step outside our academic comfort zones and explore the affordances of self-notation. Second, it was an attempt at designing experiment procedures that would be in line with the experimental tradition integral to the musicians’ practice and credo, while allowing us to maintain a degree of systematicity characteristic of experimental sciences. Third, as it assembled musicians at the crossroads of jazz, experimental and classical contemporary musics, it provided a basis for further nuanced comparisons based on the respective histories and values of those musical subcultures.

Further experiments involving notation under one guise or another were suggested during the aforementioned workshops with the Umlaut collective. Taken together, they uncovered the complex and nuanced relationship these musicians have with notation: sometimes, notation is seen as complementary to improvisation, allowing for musicians to organize a collective performance in a time-efficient way or to get out of their own habits and patterns; sometimes, it is seen as entirely superfluous, offering nothing more than what could be achieved through improvised means alone; and sometimes, it is seen as preventing improvisation from happening at all, since it puts musicians in a teleological and normative state of mind they see as incompatible with the one required by improvisation. In all of those instances, putting notation in play was instrumental in revealing key aspects of the practice of those musicians. Based on our participants at least, notation appears to be a powerful analytical tool to shed new light on the relation between improvisation and composition, and show how porous and continuous those two musical practices might be.

On a methodological level, the self-notation procedure introduced above is an attempt to design methods of data collection that largely rely on non-verbal behaviours. In a way, our experiment is similar to the methods of ethnomusicologists who ask the musicians of one community to perform variants of the same song or melody as a way to infer more abstract structures that underpin those variations.[32] Such self-notation obviously suffers from several limitations: it relies on musicians mastering some form of written notation (although, as we saw, purely verbal descriptions were also written as self-notations) and on musicians having a good enough memory of the improvisation they just performed. As such, it would probably not make much sense to apply this experiment to overly long performances, or to ask musicians to self-notate their improvisations hours after the performance. But we believe that our procedure still offers interesting specificities and thus might well be put to use in a variety of musical contexts, as long as those are not entirely alien to notation.

First, self-notation might be an interesting tool to use in a pedagogical context. It could provide an alternative tool, besides debriefing sessions and collective discussions such as the ones advocated by Alain Savouret based on his teaching of free improvisation at Paris Conservatory,[33] to reflect on one’s performances, and to better grasp which core musical ingredients make up one’s own improvisational style.

Second, in the case of collective performances, self-notation allows to track down the musicians’ perspectives not only on their own outputs, but also on their co-performers’. It thus paves the way to new studies in which self-notations would be used as a way to elicit musicians’ co-representations and shared understanding of their joint performance through a cross-reading situation.

Third, self-notation allows for the systematic comparison, within a same medium, of musicians’ self-notations with their written compositions. Self-notation here appears as an efficient way to identify the breadth of musical thinking that might be shared between the improvisational and compositional outputs of musicians, but also as a way to contrast how descriptive and prescriptive uses of notation may differ within a given community. One can only wonder what we might learn from such a procedure about the creative practices of musicians from the Art Ensemble of Chicago, the AACM or the Instant Composers Pool, to name only a few for which there are extant corpus of written compositions.[34]

Fourth, we could enrich our current understanding of the aesthetical and behavioural norms of free improvisation, essentially based on observational and verbal procedures. Alongside verbal data and neuro-imagery, often praised as the tools par excellence of scientific inquiry into music,[35] self-notation proves to be an overlooked but powerful means to shed light on musicians’ cognitive processes. As such, our experiment in self-notation-based experiments might also serve as a template for further research into those musical practices which, like free improvisation, neither shy away from, nor are defined by notation.

Recordings cited

Beliah, Sébastien. 2018. Nocturnes. Sébastien Beliah, double bass. Umlaut records, compact disc.

Corner, Philip. 2013–2014. Lifework: A Unity. Ensemble Hodos. Umlaut records, 3 compact discs.

Gerbal, Antonin. Sound of Drums. Antonin Gerbal, drums. Umlaut records, compact disc.

Mostly Other People Do The Killing. 2014. Blue. Hot Cup records, compact disc.

Rühl, Joris. 2018. Toile Étoiles. Joris Rühl, clarinet. Umlaut records, compact disc.

Endnotes

[1] Graeme B. Wilson and Raymond A. MacDonald, ‘The Sign of Silence: Negotiating Musical Identities in an Improvising Ensemble’, Psychology of Music, 40/5 (2012), 558–73, here 565.

[2] See Jeff Pressing, ‘Cognitive Processes in Improvisation’ in Cognitive Processes in the Perception of Art, ed. W. Ray Crozier and Anthony Chapman (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1984), 345–63; Derek Bailey, Improvisation: Its Nature and Practice in Music (New York: Da Capo Press, 1993); Jogn Corbett, A Listener’s Guide to Free Improvisation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016); Pierre Saint-Germier and Clément Canonne, ‘Coordinating Free Improvisation: An Integrative Framework for the Study of Collective Improvisation’, Musicae Scientiae, 26/3 (2022), 455–75.

[3] Clément Canonne, ‘Rehearsing Free Improvisation? An Ethnographic Study of Free Improvisers at Work’, Music Theory Online 24/4 (2018), DOI: 10.30535/mto.24.4.1.

[4] Clément Canonne, ‘L’improvisation libre à l’épreuve du temps: Logiques de travail et dynamiques créatives d’un duo d’improvisateurs’, Revue de musicologie, 103/1 (2017), 137–68; Floris Schuiling, The Instant Composers Pool and Improvisation Beyond Jazz (New York: Routledge, 2019).

[5] Stephen Davies, Musical Works and Performances: A Philosophical Exploration (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2001).

[6] Christopher Bartel, ‘Music without Metaphysics?’ The British Journal of Aesthetics, 51/4 (2011), 383–98.

[7] Andrew Kania, ‘The Methodology of Musical Ontology: Descriptivism and its Implications’, in The British Journal of Aesthetics, 48/4 (2008), 426–44.

[8] Pressing, ‘Cognitive Processes in Improvisation’.

[9] Bailey, Improvisation.

[10] Saint-Germier and Canonne, ‘Coordinating Free Improvisation’.

[11] Lee B. Brown, ‘Musical Works, Improvisation, and the Principle of Continuity’, in The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 54/4 (1996), 353–69; Andrew Kania, ‘All Play And No Work: An Ontology of Jazz’, in The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 69/4 (2011), 391–403.

[12] Graeme B. Wilson and Raymond A. MacDonald, ‘The Construction of Meaning within Free Improvising Groups: A Qualitative Psychological Investigation’. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 11/2 (2017), 136–46; Amandine Pras, Michael F. Schober, and Neta Spiro, ‘What About Their Performance Do Free Jazz Improvisers Agree Upon? A Case Study’, Frontiers in psychology, 8 (2017), 966.

[13] Clément Canonne and Jean-Julien Aucouturier, ‘Play Together, Think Alike: Shared Mental Models in Expert Music Improvisers’, Psychology of Music, 44/3 (2016), 544–58.

[14] Pras, Schober, and Spiro, ‘What About Their Performance Do Free Jazz Improvisers Agree Upon?

[15] Canonne and Aucouturier, ‘Play Together, Think Alike’.

[16] Canonne, ‘Rehearsing Free Improvisation?’.

[17] Brown, ‘Musical Works’.

[18] Bailey, Improvisation, 106–12.

[19] Quoted in Bertrand Denzler and Jean-Luc Guionnet, The Practice of Musical Improvisation: Dialogues with Contemporary Musical Improvisers (London: Bloomsbury, 2020), 147.

[20] Evan Parker in Denzler and Guionnet, The Practice of Musical Improvisation, 148.

[21] See for instance Seijiro Murayama (147) and Daunik Lazro (147–48) in Denzler and Guionnet, The Practice of Musical Improvisation.

[22] John Butcher in Denzler and Guionnet, The Practice of Musical Improvisation, 147

[23] Bailey, Improvisation, 108

[24] Tom Arthurs, Secret Gardeners: An Ethnography of Improvised Music in Berlin (2012–13) (PhD diss., The University of Edinburgh, 2016)

[25] John Lely and James Saunders, Word Events: Perspectives on Verbal Notation (London: Continuum, 2012)

[26] Corner, Philip. Lifework: A Unity. Ensemble Hodos. Umlaut records, 3 compact discs., 2013–2014.

[27] Clément Canonne, ‘Le piano préparé comme esprit élargi de l’improvisateur: une étude de cas autour du travail récent d’Ève Risser’, Musimédiane, 8 (2015), URL: https://www.musimediane.com/numero8/CANONNE/.

[28] Valentina Bertolani, ‘Improvisatory Exercises as Analytical Tool: The Group Dynamics of the Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza’, Music Theory Online, 25/1 (2019), DOI: 10.30535/mto.25.1.1; David Borgo, Sync or Swarm: Improvising Music in a Complex Age (London: Continuum, 2005); Clément Canonne and Nicolas Garnier, ‘Individual Decisions and Perceived Form in Collective Free Improvisation”. Journal of New Music Research, 44/2 (2015), 145–67.

[29] Nemesio García‐Carril Puy, ‘The Ontology of Musical Versions: Introducing the Hypothesis of Nested Types: Puy The Ontology of Musical Versions’, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 77/3 (2019), 241–54.

[30] Canonne and Aucouturier, ‘Play Together, Think Alike’.

[31] Canonne, ‘Rehearsing Free Improvisation?’.

[32] Simha Arom, African Polyphony and Polyrhythm: Musical Structure and Methodology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

[33] Alain Savouret, Introduction à un solfège de l’audible: L’improvisation libre comme outil pratique (Lyons: Symétrie, 2010).

[34] Paul Steinbeck, Message to Our Folks: The Art Ensemble of Chicago (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017); Schuiling, The Instant Composers Pool.

[35] Daniel J. Levitin, This is Your Brain on Music: The science of a human obsession (New York: Dutton, 2006)