Female Epiphanies in Twentieth- and Twenty-First-Century Monodrama:

Experimental Study and Artistic Production

DOI: 10.32063/0206

Francesca Placanica

Francesca Placanica, Classical Singer, has a wide background as a soloist in diverse vocal and instrumental ensembles. A recent PhD graduate from University of Southampton (2013), she also works as an artistic researcher, joining both her academic and artistic competencies. www.francescaplacanica.com

by Francesca Placanica

Volume 2

Reports + Commentaries

This report is an initial attempt to investigate the long and complex processes involved in one of the many stage works for female voice composed in the twentieth century, Recital I (for Cathy), conceived by Luciano Berio for Cathy Berberian in 1972.1)This report refers to initial work undertaken on Recital I between September 2013 and September 2014. Our fully staged adaptation for voice and piano of the work, entitled Monodrama I, was then produced on three different occasions throughout 2014 and 2015. Its première featured in the ‘New Vocalities’ event organized by Bath Spa Live and the Department of Performing Arts at Bath Spa University, under the artistic direction of Dr Pamela Karantonis (Michael Tippett Centre, 22 October 2014; Maria Garcia, piano); a second performance of Monodrama I took place during the 2014 edition of The Cornerstone Festival on the Liverpool Hope University Creative Campus, under the artistic direction of Dr. Alberto Sanna (The Cornerstone Theatre, 27 November 2014; David Walters, piano); and a third performance was hosted in Aveiro at the Auditorium of the Department of Communications and Arts DeCA, at the invitation of Jorge Salgado Correia (DeCA Auditorium, 5 March 2015; Dr. Francisco Monteiro, piano). All performances featured acting and music students of the hosting departments, who undertook a workshop on the work and played the mime characters on stage.

Further performances of the abovementioned musical monodramas will take place within the next two years under the aegis of Maynooth University, Ireland, where Francesca is currently the recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship funded by the Irish Research Council. Under the mentorship of Professor Christopher Morris, she is the leader of the project “En-Gendering Monodrama: Artistic Research and Experimental Productions”. The work is scored for mezzosoprano, two pianos, harpsichord and chamber orchestra: a total of 17 instruments. It was premiered by Berberian with the London Sinfonietta conducted by Berio, in a 1972 concert for the Calouste Gulbenkian Fundation in Lisbon. A more thorough discussion of the musicological aspects of the work and its genesis is available elsewhere, but a few insights into the score and its genealogy are necessary when discussing the practical and experimental approach to it.2)Francesca Placanica, ‘Arranging and Performing Recital I: An Open Approach to Twentieth-Century Musical Monodrama’, paper delivered at the international seminar ‘The Limits of Control’, Orpheus Research Centre in Music, Ghent, 26 February 2014 (article forthcoming).

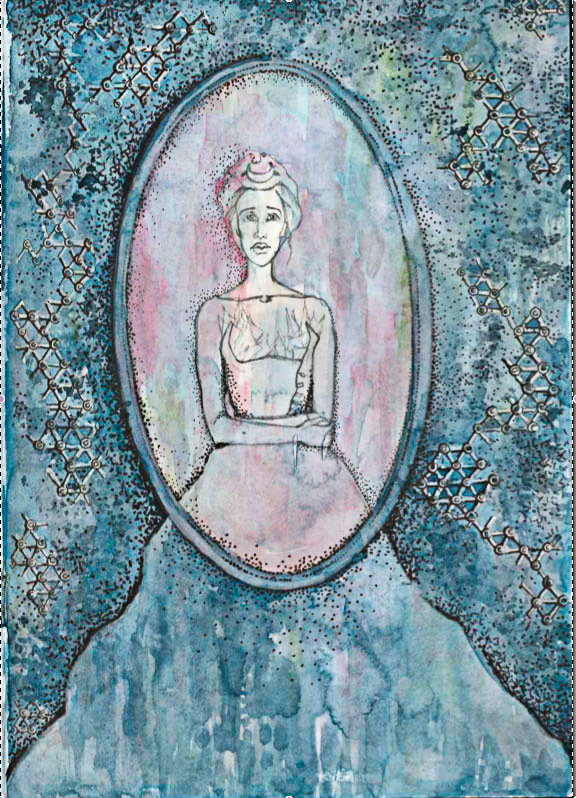

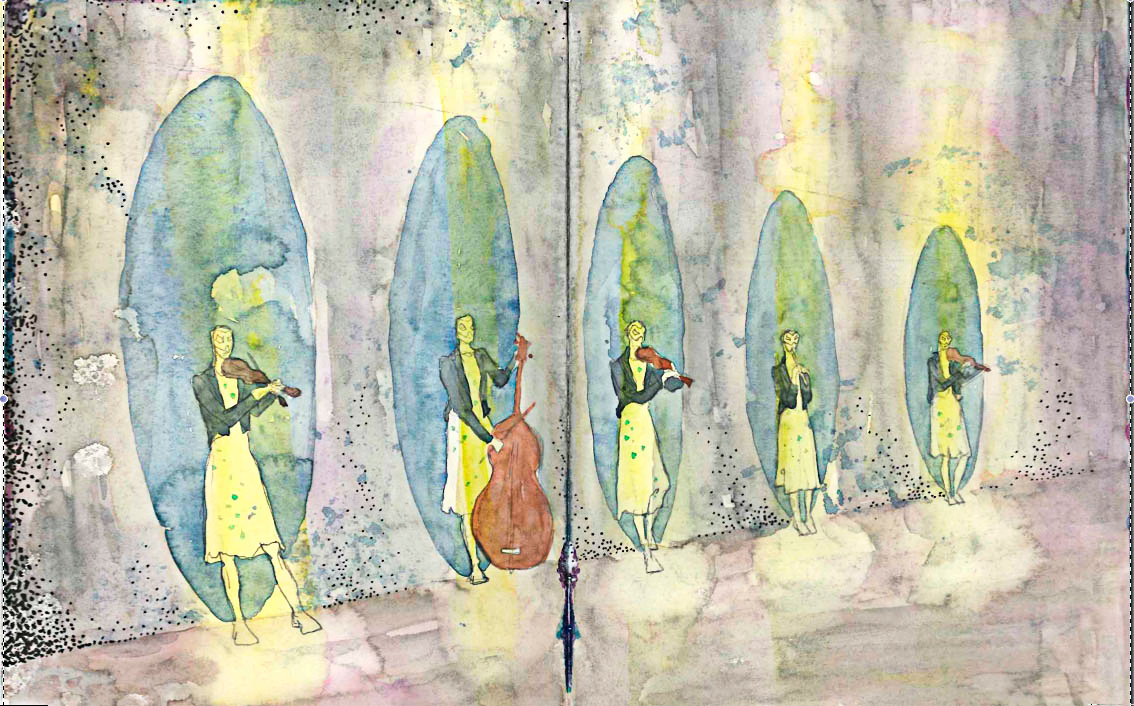

Recital I unfolds in a monologue written by Edoardo Sanguineti, Andrea Mosetti and Luciano Berio, and heavily edited by Cathy Berberian.3)For a full discussion of Berberian’s editing of the text, see Placanica, ‘Arranging and Performing Recital I’, n. 7. An actress-singer walks on stage and begins her recital, but realizes that her pianist has not shown up; she then begins to sing ‘Amor’ from Il Lamento della ninfa by Claudio Monteverdi. Having left the scene disappointed, she returns to begin her monologue, and little by little through her spoken words and scattered musical quotations she explicates, in a kind of stream of consciousness, her views on musical life combined with private vicissitudes, theatre and academic discourse, in due course making her madness apparent. The audience eventually perceives the protagonist (Figure 1) to be a patient in a nursing home, where the wardrobe mistress, who arrives to piece together her costume, is actually head nurse. In addition to the protagonist, the wardrobe mistress and the pianist, who all act on stage, a few instrumentalists emerge to populate the scene (Figure 2).

Musically, the work constitutes a heterogeneous journey through musical quotations extrapolated mainly from Berberian’s repertoire, all contained within a stream of consciousness. Within this text, as suggested by Berberian and by the performance instructions provided in the published edition of the work, performers are free to insert their own musical fragments, provided they belong to their vocal repertoire; thus the work is created anew with each performer, and is tailored to each performer’s vocal and performative strengths.4)See performance indications in Luciano Berio, Recital I (Vienna: Universal Edition, 1972/ repr. 2002). Thus, Recital I expresses its open nature through the subjective rendition of each performer, whose responses to inputs suggested by the text represent a formalized musical type of Rorschach test, triggered by the lines of the monologue. Needless to say, the piece raises numerous challenges, both vocally and physically. The interpreter negotiates between speaking and singing, with the singing voice acting as an actual and spontaneous ‘prolongation’ of the speaking voice. At the same time, an unspoken requirement of the work is the possibility of re-creating different stylistic worlds and exploring as much as possible – always in accordance with the performer’s taste and ability – the idiomatic palette available to the interpreter.5)This philosophy is indeed commensurate with Berberian’s own quintessential philosophy of the singing voice, as expressed in her manifesto, ‘La nuova vocalità nell’opera contemporanea’, see Francesca Placanica, ‘La nuova vocalità nell’opera contemporanea’ (1966): Cathy Berberian’s Legacy’, in Cathy Berberian: Pioneer of Contemporary Vocality, ed. Pamela Karantonis, Francesca Placanica, Anne Sivuoja-Kauppala and Pieter Verstraete (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014), pp. 51–66.

In coming to terms with the work itself, therefore, the performer will provide a thorough reading of the text, and nurture his or her own imagination, thus feeding a stream of consciousness to construct new and customized meaning.

‘The Artistic Turn’

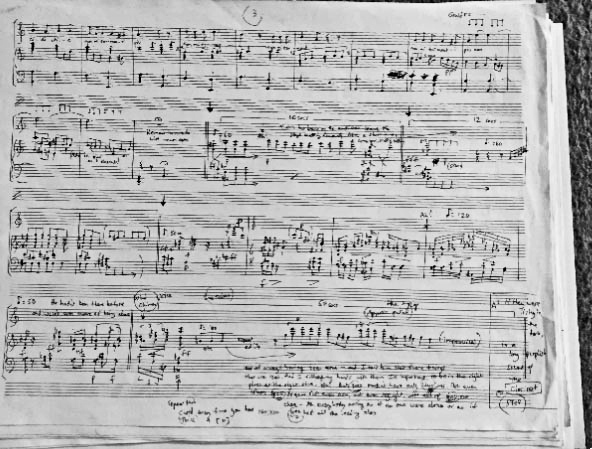

Figure 3 Douglas Gould: Recital I, Autograph Arrangement for 2014 Production, page 3 (courtesy of Douglas Gould).

My practical work on the score of Recital I began in summer 2013, with Douglas Gould producing an arrangement for piano and voice.6)Berio, Recital I, n. 9. Under the wider umbrella of an overall project on monodrama, the aim of our work was initially to embody the performer’s role in the making and delivery of the work; it thus started more as a speculative undertaking than as a process devoted to the actual performance of the work. Little by little, and encouraged by composers and musicologists encountered along the way, the project assumed a more audacious experimental side, and brought to the fore the central objective of making our new arrangement, sustained by our rationale, ultimately performable.7)A lecture recital was presented during the Biennial International Conference on ‘Music since 1900’ at Liverpool Hope University on 17 November 2013, at the international seminar ‘The Limits of Control’, Orpheus Research Centre in Music, Ghent, 26 February 2014, and at the CMPCP Conference in Cambridge in July 2014.

In this section, I concentrate in particular on my encounter with the score itself and its heavily charged background, and on processes leading to my personal rendition of it, in accordance with the performance indications within the score and inspired by Berberian.8)See Placanica, ‘Arranging and Performing Recital I’, n. 7.

The score, conceived by Berio for orchestra and soloist, presents conspicuous challenges in terms of orchestration, staging and performance. Becoming acquainted with the work and its background implied the need to observe and deconstruct it, reviving the symbolic implications that Cathy Berberian intended for the piece while compiling her musical collage. The fragments of music that Berberian first inserted represented her subjective musical reactions to the meaning conveyed by the monologue. In her hands, the text became a fluid material to which musical imagery added, amplifying its subjective meaning. These micro-responses may have been more or less manipulated and induced by Luciano Berio, who was apparently working on the score while Berberian was editing and troping the text.

While internalizing the score, I realized that the more familiar I became with the verbal monologue, the more I felt compelled to provide my own reading and interpretation of the imagery conveyed by the text and portrayed by the music. However, this process of re-appropriation, largely envisaged by Berberian and Berio in the first instance, was in my case substantially supported but also heavily biased by my background knowledge of Cathy Berberian’s orientations in choosing her repertoire. Such knowledge allowed me to interpret and disentangle her reactions to the music and the logical progression she established between text and musical fragments. One main difference stood out in the whole process: my own creative rewriting was indeed very personal and customized, and was dictated exclusively by my own experience and taste, whereas Berberian’s was certainly redirected and orientated by Berio.

In my case, the most challenging phase of re-appropriation was in fact that of escaping the strong Berberianesque imprint extant in the score and in the interpretation of the work. My choice of repertoire initially formed a dialogue between me and Berberian, as I decoded and parodied her responses. However, as I went on to memorize the piece, my own reading of the text became increasingly independent of hers: the more I inhabited the text, the less I was subject to Berberian’s and Berio’s rendition of the piece, finding it necessary almost to avoid them. I almost deliberately ‘purged’ the text of their musical associations, unless they complied with my own experience and knowledge of the piece. While adapting the piece I realized that, practically, mechanisms of reminiscence and recall, typical of performance memorization processes, were spontaneously triggered in my rewriting. A direct interpretation of the meaning of the monologue and its reflection on my own personal and artistic experience helped me retrieve memory stimuli, the imagery of which was recalled symbolically, or ironically contradicted by musical excerpts belonging to my extant repertoire. These excerpts, which functioned as metaphorical or paradoxical elements integrated into the score itself, became creative elements of my customized version of Recital I.9)Jane Ginsborg, Roger Chaffin and Alexander P. Demos, ‘Different Roles for Prepared and spontaneous Thoughts: A Practice-Based Study of Musical Performance from Memory’, Journal of Interdisciplinary Music Studies, 6/2 (2012), pp. 201–31; Jane Ginsborg and Roger Chaffin, ‘The Effect of Retrieval Cues Developed During Practice and Rehearsal on an Expert Singer’s Long-Term Recall for Words and Melody’, Proceedings of the International Symposium on Performance Science, Porto, 2007, ed. Aaron Williamon and Daniela Coimbra (Utrecht: AEC, 2007); Jane Ginsborg and John Sloboda, ‘Singers’ Recall for the Words and Melody of a New, Unaccompanied Song’, Psychology of Music, 35 (2007), pp. 421–40.

Not only did the re-creation of the musical text proceed almost simultaneously with spontaneous mechanisms of recall and response, but my work on the text and the responses I produced were already structurally incorporated when I began the memorization process. The memorization of the work overlapped with the mechanisms of recall and response triggered by the text in its new format. This acquisition process was substantially different from methods applied to the learning of songs with words. In this case, my way of proceeding was more similar to processes related to the learning of scripts for theatrical plays. This process could be described following the framework identified by cognitive researchers:10)See, for example, Helga Noice and Tony Noice, ‘What Studies of Actors and Acting Can Tell Us About Memory and Cognitive Functioning’, Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15/1 (2006), pp. 14–18.

- extensive elaboration (imaginative embellishment);

- perspective taking (adopting the perspective of one character in a narrative);

- self-referencing (relating material personally to oneself);

- self-generation (remembering one’s own ideas better than ideas of others);

- mood congruency (matching one’s mood to the emotional valence of the material); and distinctiveness (considering details that render an item unique).

Quite strikingly, this framework also structurally fitted the process of re-elaboration undertaken on the score, and presided over the criteria for the application of the new fragments, naturally stimulating mechanisms of recall and response emerging from the text. The processes leading the structural functioning of the musical components of this stream of consciousness were typical of memorization processes.

The connection between memory and musical writing on the one hand, and embodiment and creativity on the other, sheds light on the strong psychoanalytical implant of the work. Recital I, with its open nature, is the acid test of performers’ subjective acquaintance with their musical repertoire, and requires performers/composers to narrow the boundary between their subjectivity and performance skills. The performer gains at least the same centrality as the composer, and becomes the exposed medium of her/his own stream of consciousness that, through processes related to memory and subjectivity, relinquishes the realm of interpretation to become the naked embodiment of the self.

The ‘Recital’ envisaged by Berberian and Berio is therefore an arena in which the solo singer not only ‘plays’ the protagonist of the work, but also becomes the scapegoat of his or her personal and idiomatic artistic self-reflection.

The Project

Video 1 Project trailer: One-Woman Act: (Post-)Modernist Monodrama.

Recital 1 is a part of a trans-disciplinary study of twentieth-century musical monodrama, which focuses on modern musical stage works set for female solo performer. Through methodologies and creative processes appropriate to artistic research and applied to a number of case studies (among them Recital 1), this undertaking critically challenges the role of female solo performers in this genre, and integrates artistic experimentation as an additional structural element to the discourse.

Musical monodrama is a form of melodrama that originated in Germany in the late eighteenth century, featuring one character, sometimes with chorus, and alternating speech with short passages of music or sometimes speaking over music.11)Anne Dhu McLucas, ‘Monodrama’, in D. Root, ed., Grove Music Online (accessed 4 August 2014). In modern times, the term is usually used to define a one-character opera, as in Schoenberg’s Erwartung (performed 1924), Poulenc’s La voix humaine (1959), Berio’s Recital I (1972) and Feldman’s Neither (1977), which all feature in this project. Twentieth- and twenty-first-century composers have almost exclusively conceived musical monodramas as the natural performance space of a female performer and a female stream of consciousness, emphasizing the lyrical qualities of the female voice, and adopting it as their favourite means to inspire their creative process. They undoubtedly drew on the experiments of their literary contemporaries, such as James Joyce, e.e. cummings and Jean Cocteau. However, in this case the composer was able to rely on an additional agent, the female performer, who contributed a unique personal interpretation of the poetic and bodily narrative to the piece, thus amplifying the dramatic space and expanding the gamut of expressive means. The ultimate objective of this project is to challenge and expand the creative role of the female performer in the production and delivery of twentieth- and twenty-first-century musical monodrama, introducing experimental performative processes led by the female artist-researcher as a contribution to the ongoing discourse on authorship, identity and subjectivity in the genre.12)Judith Butler, Bodies that Matter (New York: Routledge, 1993); Ruth A. Solie, ed., Musicology and Difference: Gender and Sexuality in Music Scholarship (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993).

The theoretical question underpinning the research originates from Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht’s essay Production of Presence, Interspersed with Absence: A Modernist View on Music, Libretti, and Staging. Gumbrecht frames opera as the product par excellence of a culture of presence rather than meaning, and defines the core of opera as the ‘epiphany of a synaesthesia of substances’.13)Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, ‘Production of Presence, Interspersed with Absence: A Modernist View on Music, Libretti, and Staging’, in Music and the Aesthetics of Modernity: Essays, ed. Karol Berger and Anthony Newcomb (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005), pp. 343–56.

Gumbrecht argues that an ideal production is one that supports, develops and brings out the epiphany of musical substance: the complexity and intensity of the interplay of voice and instruments and the filling of space on the stage, as well as favouring the choreography of bodies over the mimetic play of costumes, gestures and facial expressions. The entrances and exits of the various singers, then, and the way in which their voices strike up and fall silent, create strong event effects. Whereas Gumbrecht’s analysis focuses on multi-character opera, in musical monodrama, in which there is no interaction between the dramatis personae, a single performer is responsible for recreating an equivalent to such ‘events’ in a constant dialectic between presence and absence. Musical monodrama therefore represents a unique case, because the embodiment of a single character on the stage accentuates its present-ness more than any other operatic form: the performing body of the soloist plays a conspicuous part in the epiphany of synaesthesia.

Starting from research and experimentation on a traditional patriarchal repertoire, this project incorporates a new vision of the role of female solo performers in twentieth- and twenty-first-century musical monodrama, and integrates the gender-orientated experience of the artist-researcher as a structural element of the discourse in the genre of musical monodrama. The outcomes of this work add critical inquiry to the performance milieu expressed by modernist and post-modern musical monodramas in the making, thus aiming to re-define and re-locate the role of the solo female performer, and to test new performative devices and dramatic possibilities in the repertoire. The musicological background to the experimental research emphasizes particularly the connection between the creation of the work and the role of its first performer, philologically reconstructing the earliest performances of each work. On the artistic side, in undertaking the process of inhabiting, producing and performing these works, the artist-researcher will field test her embodied role in the creative process.

This multi-faceted vision challenges the traditional definition of the genre, obfuscated until now by its contamination with other musical forms, and traces its development in the twentieth- and twentieth-first centuries, investigating the genealogy and implications of works created for solo female performer against the backdrop of historical, performance and sociological backgrounds. In particular, the artistic research carried out on musical and dramaturgical materials will retain quintessential contemporary accounts from other performing arts repertoires centred on the solo female interpreter, evidencing the physiological connections that the embodiment of the female interpreter has been able to re-create and evoke across performing arts.

In addition, through its experimental approach, the project challenges and expands the role and subjectivity of the female solo performer in current performing arts, thus observing empirically how the female body, voice and narrative became predominant in twentieth-century aesthetics related to solo performance and has carried through to the present time.

Ultimately, modernist musical monodrama evokes the aesthetics of the Renaissance and baroque lamento, a genre that also envisaged the introduction of extemporary vocal embellishments and spoken inflections known as recitar cantando. Originating in ancient Greek drama and further developed in Latin poetry, the lament topos enjoyed a privileged status in European literature and theatre. Featured in exceptional moments of emotional climax or particularly intense expression, it provided an occasion for special formal development and for the display of expressive rhetoric and affective imagery. Laments were most often associated with female characters and the female voice.14)Wendy Heller, Emblems of Eloquence: Opera and Women’s Voices in Seventeenth-Century Venice (Oakland CA: University of California Press, 2004); Elizabeth Anderson, ‘Dancing Modernism: Ritual, Ecstasy and the Female Body’, Literature and Theology, 22/3 (2008), pp. 354–67; Andrew Parker and Eve Kosofsky, eds, Performativity and Performance (New York: Routledge, 1995); Carrie Preston, Modernism’s Mythic Pose: Gender, Genre, Solo Performance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011). Self-pity and a free stream of consciousness over a loss or abandonment were the emotional landmarks of the genre, which was increasingly structured into rigid metric and harmonic grids and eventually emancipated as an independent semi-staged form.

In arguing that twentieth-century monodrama paralleled baroque laments in genere rappresentativo and classical cantatas scenicas, this research ties modernist musical monodrama to the aesthetics of loss, absence and betrayal already extensively explored in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century solo performance.15)A few examples of the genre are Monteverdi’s Il Lamento di Arianna (1607–08), D’India’s and Monteverdi’s Il Lamento di Olimpia (resp. 1623; c. 1620), Haydn’s Arianna a Naxos (1789). As in the case of the baroque recitar cantando typical of those genres, modernist and post-modern monodrama became a productive crucible for vocal experimentation and extended vocal technique. As observed above, Recital I fits perfectly the scope and framework of the research with its baroque reminiscences and psychoanalytic layers.

Thus, this research reconsiders the weight imposed by and on the solo female protagonist, enacts a radicalization of gender and sexuality on stage, and redistributes the forces present during the staging process, in which the solo female interpreter becomes a creative agent in the dramatic process. The artistic research methodology interrogates musical materials, providing an original insight into twentieth- and twenty-first-century musical monodrama. At the same time, the experimental process analyzes and experiments with creative processes in the making, and proposes alternative readings of contemporary staging. Therefore, the investigation relies extensively in its documentary section on primary sources (scores, letters, reviews, etc.) and on secondary literature relating to the genealogy of the works studied, and adopts data collection strategies typical of ‘field’ work (such as participant observation, performance ethnography, ethnodrama, biographical/autobiographical/narrative inquiry, etc.) entailed by the artistic approach applied to the works.

Staging a monodrama with a solo female protagonist triggers a set of expectations and processes that mirror contemporary attitudes toward the ‘female’ in Western culture. A solitary female performer commands the entire theatrical stage, and the way in which her manifestation embodies this challenge necessarily has to do with her identity and marketability. The project looks at sexual and gender exploitation and appropriations of performance devices associated with the ‘female’ (including the voice, high register, screaming, losing power, etc.), through or despite the embodiment of the performer’s subjectivity, and proposes an innovative reading based on historical performance practices and performances transferred to the current performance scene. This artistic research approach promises original findings through experimental acquaintance with the repertoire, and aims ultimately to integrate the active role of the female performer into the definition of musical monodrama. Furthermore, this project interrogates a field occupied predominantly by female performers on one side and male composers on the other, challenging traditional notions of authorship – a topic still extant in the current epistemological debate – and of composition, and questioning the creative imprint injected by the performer during both creative and performance processes.16)See for instance Michel Foucault, ‘What is an Author?’ Lecture presented to the Societé Francais de Philosophie on 22 February 1969, translated by Josué V. Harari.

Footnotes

References

| ↑1 | This report refers to initial work undertaken on Recital I between September 2013 and September 2014. Our fully staged adaptation for voice and piano of the work, entitled Monodrama I, was then produced on three different occasions throughout 2014 and 2015. Its première featured in the ‘New Vocalities’ event organized by Bath Spa Live and the Department of Performing Arts at Bath Spa University, under the artistic direction of Dr Pamela Karantonis (Michael Tippett Centre, 22 October 2014; Maria Garcia, piano); a second performance of Monodrama I took place during the 2014 edition of The Cornerstone Festival on the Liverpool Hope University Creative Campus, under the artistic direction of Dr. Alberto Sanna (The Cornerstone Theatre, 27 November 2014; David Walters, piano); and a third performance was hosted in Aveiro at the Auditorium of the Department of Communications and Arts DeCA, at the invitation of Jorge Salgado Correia (DeCA Auditorium, 5 March 2015; Dr. Francisco Monteiro, piano). All performances featured acting and music students of the hosting departments, who undertook a workshop on the work and played the mime characters on stage. Further performances of the abovementioned musical monodramas will take place within the next two years under the aegis of Maynooth University, Ireland, where Francesca is currently the recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship funded by the Irish Research Council. Under the mentorship of Professor Christopher Morris, she is the leader of the project “En-Gendering Monodrama: Artistic Research and Experimental Productions”. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Francesca Placanica, ‘Arranging and Performing Recital I: An Open Approach to Twentieth-Century Musical Monodrama’, paper delivered at the international seminar ‘The Limits of Control’, Orpheus Research Centre in Music, Ghent, 26 February 2014 (article forthcoming). |

| ↑3 | For a full discussion of Berberian’s editing of the text, see Placanica, ‘Arranging and Performing Recital I’, n. 7. |

| ↑4 | See performance indications in Luciano Berio, Recital I (Vienna: Universal Edition, 1972/ repr. 2002). |

| ↑5 | This philosophy is indeed commensurate with Berberian’s own quintessential philosophy of the singing voice, as expressed in her manifesto, ‘La nuova vocalità nell’opera contemporanea’, see Francesca Placanica, ‘La nuova vocalità nell’opera contemporanea’ (1966): Cathy Berberian’s Legacy’, in Cathy Berberian: Pioneer of Contemporary Vocality, ed. Pamela Karantonis, Francesca Placanica, Anne Sivuoja-Kauppala and Pieter Verstraete (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014), pp. 51–66. |

| ↑6 | Berio, Recital I, n. 9. |

| ↑7 | A lecture recital was presented during the Biennial International Conference on ‘Music since 1900’ at Liverpool Hope University on 17 November 2013, at the international seminar ‘The Limits of Control’, Orpheus Research Centre in Music, Ghent, 26 February 2014, and at the CMPCP Conference in Cambridge in July 2014. |

| ↑8 | See Placanica, ‘Arranging and Performing Recital I’, n. 7. |

| ↑9 | Jane Ginsborg, Roger Chaffin and Alexander P. Demos, ‘Different Roles for Prepared and spontaneous Thoughts: A Practice-Based Study of Musical Performance from Memory’, Journal of Interdisciplinary Music Studies, 6/2 (2012), pp. 201–31; Jane Ginsborg and Roger Chaffin, ‘The Effect of Retrieval Cues Developed During Practice and Rehearsal on an Expert Singer’s Long-Term Recall for Words and Melody’, Proceedings of the International Symposium on Performance Science, Porto, 2007, ed. Aaron Williamon and Daniela Coimbra (Utrecht: AEC, 2007); Jane Ginsborg and John Sloboda, ‘Singers’ Recall for the Words and Melody of a New, Unaccompanied Song’, Psychology of Music, 35 (2007), pp. 421–40. |

| ↑10 | See, for example, Helga Noice and Tony Noice, ‘What Studies of Actors and Acting Can Tell Us About Memory and Cognitive Functioning’, Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15/1 (2006), pp. 14–18. |

| ↑11 | Anne Dhu McLucas, ‘Monodrama’, in D. Root, ed., Grove Music Online (accessed 4 August 2014). |

| ↑12 | Judith Butler, Bodies that Matter (New York: Routledge, 1993); Ruth A. Solie, ed., Musicology and Difference: Gender and Sexuality in Music Scholarship (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993). |

| ↑13 | Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, ‘Production of Presence, Interspersed with Absence: A Modernist View on Music, Libretti, and Staging’, in Music and the Aesthetics of Modernity: Essays, ed. Karol Berger and Anthony Newcomb (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005), pp. 343–56. |

| ↑14 | Wendy Heller, Emblems of Eloquence: Opera and Women’s Voices in Seventeenth-Century Venice (Oakland CA: University of California Press, 2004); Elizabeth Anderson, ‘Dancing Modernism: Ritual, Ecstasy and the Female Body’, Literature and Theology, 22/3 (2008), pp. 354–67; Andrew Parker and Eve Kosofsky, eds, Performativity and Performance (New York: Routledge, 1995); Carrie Preston, Modernism’s Mythic Pose: Gender, Genre, Solo Performance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011). |

| ↑15 | A few examples of the genre are Monteverdi’s Il Lamento di Arianna (1607–08), D’India’s and Monteverdi’s Il Lamento di Olimpia (resp. 1623; c. 1620), Haydn’s Arianna a Naxos (1789). |

| ↑16 | See for instance Michel Foucault, ‘What is an Author?’ Lecture presented to the Societé Francais de Philosophie on 22 February 1969, translated by Josué V. Harari. |