Disruption and Discipline:

Approaches to Performing John Cage’s Concert for Piano and Orchestra

Read as PDF

Table of Contents

DOI: 10.32063/0506

Philip Thomas, Martin Iddon, Emily Payne

Philip Thomas is a Professor of Performance at the University of Huddersfield, having joined the institution in 2005. He specialises in performing and in writing about new and experimental music, including both notated and improvised music. As a performer, he places much emphasis on each concert being a unique event, designing imaginative programmes that provoke and suggest connections. More details about Philip’s work and forthcoming events can be found at https://www.philip-thomas.co.uk/.

Martin Iddon is a composer and musicologist. He joined the staff at the University of Leeds in December 2009, having previously lectured at University College Cork and Lancaster University. Martin studied composition and musicology at the Universities of Durham and Cambridge and has also studied composition privately with Steve Martland, Chaya Czernowin, and Steven Kazuo Takasugi. His musicological research has largely focussed on post-war music in Germany and the United States of America. His books New Music at Darmstadt, John Cage and David Tudor, and John Cage and Peter Yates are published by Cambridge University Press.

Emily Payne is a Lecturer in Music at the University of Leeds, having joined the department as a Postdoctoral Research Assistant on the AHRC-funded project, ‘John Cage and the Concert for Piano and Orchestra’ (2015–18). Her work is published in Contemporary Music Review, Cultural Geographies, Music & Letters and Musicae Scientiae. She is co-editor of the Oxford Handbook of Time in Music (forthcoming, 2020) and Material Cultures of Music Notation: New Perspectives on Musical Inscription (Routledge, forthcoming, 2020).

by Martin Iddon, Emily Payne and Philip Thomas

Music & Practice, Volume 5

Repertoires & Styles

A Critical Incident

The circumstances of the first performances of John Cage’s Concert for Piano and Orchestra are the stuff of Cage legend and are among the earliest instances of critical incidents leading to presumptions of a distinct, Cageian performance practice. The (bad) behaviour and interpretations of the orchestral musicians in both the world and European premiere performances have since formed the basis of a reactionary performance ideal, exemplifying the antithesis of the ego-less and disciplined approach Cage’s music is thought to require. By contrast, the interpretative methods of pianist David Tudor, who performed in both premieres, are upheld as the model par excellence of the rigorous, imaginative and intelligent responses Cage’s indeterminate music invites. This essay first outlines the historical evidence from the early performances, examining recordings and other documentation, and secondly considers the potentialities of the music and its conditions beyond those typically associated with early (and some later) recordings. In doing so, it draws upon extensive interviews with, and performances by, the British ensemble Apartment House.[1]

The premiere performance of the Concert, at an expectant New York Town Hall on 15 May 1958, formed the finale of a lengthy and varied programme surveying twenty-five years of Cage’s music. It has become notorious for the increasingly volatile reaction from the audience, who became ever more vocal and animated in the final part of the programme, which featured some of Cage’s more recent, chance-derived music: Music for Carillon no. 1 (1952), Williams Mix (1952), and the Concert for Piano and Orchestra (1957–58). The lively audience response was apparently matched by the behaviour of the thirteen musicians that comprised the ‘orchestra’ – seven strings, three woodwind and three brass, many of these doubling instruments – whose conduct was described by Cage as ‘foolish and unprofessional’ and who, according to composer and scholar Fredric Lieberman, ‘were not following what they had on the page. Many were hitting their music stands and laughing with each other’.[2] However, depictions of such behaviour are absent from the vivid description of the event provided by George Avakian (whose wife, Anahid Ajemian, was playing the first violin part). Avakian recorded the performance – and the concert as a whole – and this recording quickly became a landmark release, making available an overview of Cage’s music to a wide and international public for the first time. Avakian attributed the disruption to stemming not from the musicians but entirely from the audience, perhaps in part a symptom of his considerable personal investment in the project.[3] Calvin Tomkins points to the difficulties of performing in such disruptive circumstances, stopping just short of praising the musicians’ behaviour: ‘Midway through [the Concert] a group in the rear of the balcony stood up and tried to stop the performance with a sustained burst of applause and catcalls. The orchestra played on, despite increasing competition from the other side of the footlights’.[4]

Whether or not the musicians were seen to be disruptive during the performance (and it is impossible from the recording to determine how much of the audience laughter is directed at the theatrical events taking place on the stage), disruption of another sort there certainly was, at least from some of the musicians performing. Rhetorical ‘hunting’ gestures and jazz riffs from the trumpeter, Mel Broiles, and a quotation from Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du printemps played by tubist Don Butterfield (who also apparently made the most of the theatrical possibilities of negotiating two tubas) are the most notable (and notorious) of the deviations from Cage’s music that are audible on the recording made by Avakian, and are doubtless the main culprits leading to Cage’s verdict of unprofessionalism.[5]

The difficulty in ascertaining which of the sounds are the result of obeying, or at least reasonably interpreting, Cage’s instructions and detailed notations, and which are not, is considerable. The music is characterised by extremities of pitch and dynamics, unusual playing techniques, noises, and freedoms to make sounds not directly specified; however, as is explored further below, all parts include a ‘rule’ demanding single sounds (thus the riffs and quotations mentioned above may be understood as clear deviations). The aural results, and the physical manoeuvring sometimes necessary to execute many of the techniques stipulated (especially in the most obviously theatrical trombone solo) lend themselves to comedy: it is quite conceivable that the audience laughter heard on the recording is the direct result of the musicians doing precisely what the music asks of them. Furthermore, one should not forget the actions of Tudor, who was seen to be ‘fiddling with dials to produce electronic sounds as often as he was at the keyboard. And he was plucking and punching the strings more often than he was striking the keys in the conventional way. Toward the end he jiggled a “slinky” up and down’.[6] Other evidence suggests that Tudor was, at least at one point, ‘underneath the piano on his hands and knees’.[7] Very few of these actions are directly suggested by the notations of the Solo for Piano but Cage’s ire was never directed at Tudor, who proved to be a lasting influence upon Cage’s performance ideal long after Tudor had all but ceased to play the piano in public. Instead, it is the actions of the orchestral musicians which have become the subsequent reference point for the portrayal of undisciplined and poor performances of Cage’s music. The dubious example set by them was cited by Cage himself, as well as others, and the condemnations were repeated again and again throughout his life.

Heightening this narrative of orchestral unruliness, and possibly becoming confused with it, are the reports of the European premiere, which occurred four months later in Cologne, and in which Cage had an even unhappier time with the musicians. Despite working with the performers individually, in one-to-one rehearsals, Cage found that ‘the result was in some cases just as unprofessional in Köln as in New York’.[8] Rather more vividly, Carolyn Brown argues that the ‘rude, demonstrative audience reaction’ encouraged the players’ behaviour; she recalls that, after the concert, Cage got ‘royally drunk’ and confessed ‘that in the middle of the performance he’d prayed: “Forgive them, Lord, they know not what they do”’.[9] Unlike the New York performance, no recording of the concert is publicly available; nevertheless a recording does exist and is held at the Westdeutscher Rundfunk in Cologne. Despite the account above, the performance is, by and large, an accurate portrayal of the instrumental demands of the piece, displaying dynamic range, unusual instrumental techniques and a variety of noises. There is little to compare with the Stravinsky quotation inserted in the first performance, although the clarinettist, Martin Härtwig, provides the most attention-seeking moment, playing a childishly taunting melody – not only an act of disruption to the musical demands but also one that strikes a note of defiance. Given the remarks by Brown and Cage, it may well be that a number of other means of making both composer and audience aware of the musicians’ discontent were employed, but these are undetectable in the audio recording.

Both performances were subsequently used as justifications for proposing a mode of performance which requires musicians to adopt Cage’s own ideals and even his methods, exposing a tension between the supposed freedoms extended through the indeterminate notations and the kinds of earnest and sincere approaches Cage appeared to expect of those whom he required to transform such notations into sound. The predicament is acknowledged by Cage, who wrote, not long after these performances, ‘I must find a way to let people be free without their becoming foolish. So that their freedom will make them noble. How will I do this? That is the question.’[10] However, rather than using the opportunity to question his own methods, Cage placed the emphasis upon performers and their need to shape up to the mark, at least publicly. Reflecting on the experience twelve years later, he suggests that the performer might ‘use similar methods to make the determinations that I have left free, and will if he’s in the spirit of the thing.’[11] And, referring to the orchestra musicians of the Concert, Don Butterfield in particular, he proposes that performers, instead of doing what they wish, should follow him and his methods. Using language that is extraordinary in its religious overtones, he implies that something little short of a Damascene conversion is necessary in order to perform his music appropriately:

I have tried in my work to free myself from my own head. I would hope that people would take that opportunity to do likewise. … [T]he reason we are afraid is because we have this overlap situation of the Old dying and the New coming into being. When the New coming into being is used by someone who is in the Old point of view and dying, then that’s when that foolishness occurs.’[12]

Continuing the theme, more recently Austin Clarkson has suggested that the ‘success of a performance depends on finding musicians who are willing to put not only their abilities as performers on the line, but their imaginative and spiritual capacities as well.’.[13]

Composer Earle Brown was (and remained until fairly recently) a lone critical voice within the Cage circle concerning the elder composer’s performance demands, citing Cage’s referencing of Tudor as his model performer as problematic:

He thought, when he started doing chance music, that everyone was going to be David Tudor. David could dress up in white bow tie and tails, blow a duck whistle and pour water into a saucepan in the most elegant way imaginable. But when you put it in front of the Cologne Radio Orchestra, they all clown it up, they’re embarrassed, and they don’t know how to be free with honour. He was incensed. But he wouldn’t say don’t do. He was so devoted to so-called letting-everybody-do-what-they-want-to-do, and then he’d be very disappointed that they were not noble. David was always noble, and John thought an orchestra was going to act like seventy-five David Tudors.[14]

More recently, Benjamin Piekut and Ryan Dohoney are among those who have examined similar critical incidents with respect to Cage’s notion of indeterminacy and performance, discussing pieces including Atlas Eclipticalis (1961–62), 26’1.1499” for a String Player (1953–55) and Songbooks (1970) and the degree to which performers’ responses to the perceived openness of the instructions and notations adhere to, or deviate from, the letter of the law.[15]

The Performers

Although little is known about some of the players in the first performance, notably the string players other than Anahid Ajemian, or about how Cage sourced them, it is clear that the wind and brass players were not simply hired in for the occasion but were selected for their particular skill sets. Cage sought out players who worked, at least in part, as session musicians, and in jazz and Broadway contexts. He needed players who would be amenable to the kinds of innovative techniques and sounds he wanted for the piece; indeed, he worked with each of them to learn more about their instruments’ capabilities and limits, showing himself to be open to suggestions from the players, if not actively seeking out and integrating their input.[16] One such player was trombonist Frank Rehak, who reflected on his encounter with Cage:

I remember that we spent a long time with the instrument, taking it apart, playing without slide, without mouthpiece, adding various mutes, glass on the slide section, minus tuning slide, with spit valve open, and any other possibilities of producing a sound by either inhaling or exhaling air through a piece of metal tubing. We also discussed double stops, circular breathing, playing without moving slides, and on and on.[17]

It was clear at this stage that Cage knew at least that the notation would be indeterminate in some way, having telephoned Rehak ‘to ask if I were able to play the sliding trombone without having the notes written out in front of me’.[18] Although Cage was not known as a jazz lover, he had history, most especially during the early 1940s while he was living in Chicago, during which period he was composing mostly percussion music. Sabine Feisst argues that it was the ‘noise’ of jazz, which attracted Cage,[19] and a direct link can be made between this and Cage’s turning to jazz musicians to best project the often outlandish gestures of the Concert. Other evidence points to Cage’s notionally conceiving the work as his ‘jazz piece’, not least his description of his subsequent orchestral composition, Atlas Eclipticalis, as ‘essentially the Concert for piano and orchestra without the jazz sounds’ (note the reference to jazz ‘sounds’ as distinct from ‘jazz’).[20]

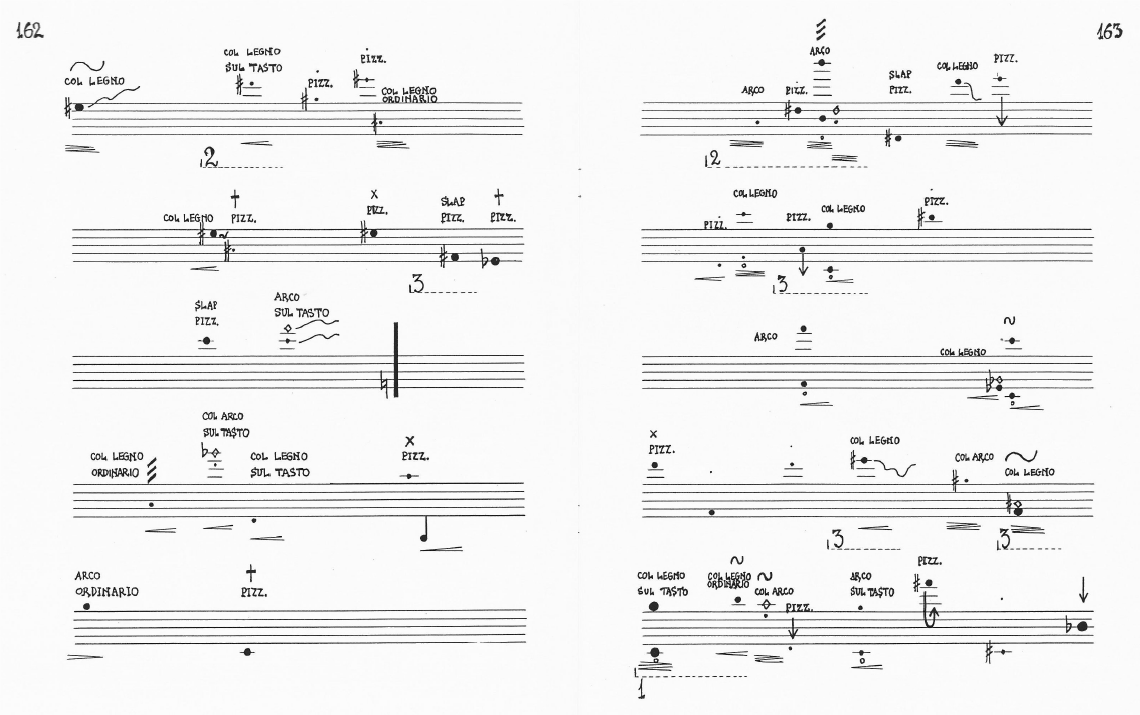

Having got his musicians ‘on side’, exploiting their willingness to experiment to the extreme with their instruments and techniques, Cage set a quite different challenge in the notations he subsequently presented them with.[21] Adopting the method used in his earlier Music for Piano series (1952–62), each page of the instrumental solos consists of five staves, across which notes of three different sizes are distributed freely in space. Some pages are dense with notes, others are much sparser, and some are entirely empty. Note-heads are assigned indications of dynamics, means of articulation, various instrument-specific techniques, such as the use of vibrato, mutes and harmonics, and directions for adapting or playing the instrument in unusual ways. Additional note-heads on a line underneath the staff demand noises of various kinds. Some instrumental parts are specific and detailed with regard to performance directions; others leave more that is free or open to interpretation. Durations are not indicated, but the performer may interpret the size of note-heads in relation to duration or dynamics or both.

Other than the idea that individual notes may be long, short, or somewhere in between, no duration is specified for any page, staff or other way of dividing up the material. Pages may be omitted: the instructions for some solos that suggest that pages may not be repeated might be read as allowing repeats in others; some solos allow the player to add silences. One direction which is consistent across all solos is that ‘[a]ll notes are separate from one another in time, preceded and followed by a silence (if only a short one).’, circumventing the possibility of creating sequences or phrases of sounds. The players, then, are offered considerable freedoms, alongside a great many restrictions. Some indications appear to contradict each other, as where pitches are combined with techniques which will change the pitch in some way or where the use of a particular articulation is cancelled by another technique that is required simultaneously. Sounds are frequently rendered unstable or inaudible, while pitches may be made noisy by their accompanying performance directions. The notation might be variously viewed as a sketch, a provocation, a granting of licence, or as a set of constraints.

One can only imagine the impression Cage’s notation made upon all the orchestral musicians, no matter their background. Just as for musicians today, the degrees of freedom offered, combined with the at times explicit, at times ambiguous instructions, would probably have resulted in reactions and understandings quite different from one player to another. For those most familiar with improvisational contexts, as the woodwind and brass players most certainly were, there might have been some resonance, albeit expressed quite differently, with the kinds of shorthand notations common to jazz and some other forms of popular music. Less familiar would have been the stipulation that each player plays as a soloist, with no pre-determined synchronisation with the other members of the orchestra. The sense of individual responsibility – or licence – would have been starkly felt. It is, then, perhaps no surprise that some players, even after having been talked through their parts with Cage, when it came to the performance, late at night, before a lively audience, responded to the occasion, the environment within which they were playing, the humour and absurdity of the music, and the sounds around them. Cage’s discontent arose from his wanting a particular kind of musician to play his music, but only if they were willing to leave a particular facet of their musicianship at the door. The sounds and timbres, but not the practices, of jazz were to be celebrated.

The convergence between music which is improvised and that which is indeterminate in its notation has come under some scrutiny. Michael Kirby makes a clear distinction between the two in his 1965 essay ‘The New Theatre’, in which he argues that the amount of spontaneous decision-making and the degree of change in improvisation, allowing for surprise and unprepared actions, differentiates it from indeterminacy, in which ‘the alternatives are quite clear, although the exact choice may not be made until performance. And the alternatives do not matter: one is as good as another’.[22] Cage articulated the difference similarly in a 1982 interview:

[I]mprovisation frequently depends not on the work you have to do (i.e. the composition you’re playing) but depends more on your taste and memory, and your likes and dislikes. It doesn’t lead you into a new experience, but into something with which you’re already familiar, whereas if you have work to do which is suggested but not determined by a notation, if it’s indeterminate this simply means that you are to supply the determination of certain things that the composer has not determined. Who is going to think of the Art of The Fugue of Bach, which leaves out dynamics altogether, who is going to think of that as in improvisation?[23]

George Lewis views the distinction differently, citing Anthony Braxton’s argument for the substitution of one term for the other as being a means of conveniently ignoring ‘“the influence of non-white sensibility.” Why improvisation and non-white sensibility would be perceived by anyone as objects to be avoided can usefully be theorized with respect to radicalised power relations’.[24] Elsewhere Lewis suggests that indeterminacy was developed as a means of harnessing the spontaneity of jazz and bebop within (and thereby maintaining) a Eurological framework.[25] The fuzziness between the two terms is explored further by Benjamin Piekut, who also cites the inconsistencies between Cage’s own improvisational practices in the 1960s and 1970s (primarily through his performances with electronics) and his strict regulation of rehearsal hours in later orchestral music.[26]

The status of the Concert was, in fact, confused from the start, with advance publicity for the programme heralding its freedom in performance as being, in the words of promoter Emile de Antonio, ‘characteristic of improvised jazz but unfamiliar in serious music’. An early review described Cage, not entirely accurately, as having ‘gone Dixieland improvisation a step better by giving performers pieces of different music, and suggesting they use any piece they want, and whatever order’.[27] Such readings have confused the reception and performance of Cage’s music ever since: a common perception, still prevalent today, is that Cage’s music permits an ‘anything goes’ approach, often assumed in connection with the composer’s references to anarchy in his writings. But the reality is that Cage’s indeterminate music almost always consists of notations to be read and interpreted alongside a set of instructions. This is no less true of his later pieces with the word ‘improvisation’ in the title, such as cComposed Improvisation (for One-Sided Drum With or Without Jangles) (1987–90) than it is for the Concert. cComposed Improvisation requires considerable working out in advance, following Cage’s quite complex instructions for the construction of a chance-determined score, in similar manner to Variations I (1958) and Variations II (1961). Even the ostensibly loosest of all his compositions, such as the later Variations (III–VIII, 1962–68) or Electronic Music for Piano (1964) contain directions and suggestions that circumscribe a field of operation within which certain actions are to be fulfilled.

Cage’s instructions for each of the instrumental solos in the Concert, while not as oblique as the pieces just cited, are nonetheless complex, with much to take in. While players may, of course, annotate their parts, making decisions in advance as to ways of playing, the notation still suggests a degree of freedom and spontaneity, at least with regard to dynamics and durations. This tension, often described as being one between discipline and freedom, is made explicit in Cage’s pronouncements on early performances of the Concert, in which his adulation of the creative prowess of Tudor (whose realisations of the Solo for Piano were almost certainly not guided or even necessarily ‘approved’ by Cage) contrasts with his description of the orchestral musicians. This is despite the fact that they, too, on the basis of the recordings, adhered, on the whole, to the demands of the score in a reasonable manner, even if there is little doubt that some also responded to the occasion with some loose and spontaneous playing. That said, Tudor himself had described the piece, in a letter to Stockhausen written while the Concert was still being composed, with the prediction that it would be ‘very wild’. And arguably, although Tudor’s realisation was, typically, highly prepared and ‘disciplined’, it also featured some playing and actions that were decidedly out of the ordinary.[28] Cage himself used the same word as Tudor with reference to Butterfield’s playing in the first performance: ‘He was just going wild – not playing what was in front of him, but rather whatever came into his head’.[29]

It would seem, then, that not only is the negotiation between instructions and notation one to be handled sensitively, but the degrees of freedom one might infer in the music are to be understood in relation to a hidden line of acceptability. Such a line would seem to demarcate an ascetic performance sensibility from a livelier and more spontaneous one. Yet, that the very musicians whose behaviour Cage derided in this first performance were precisely those whom he selected to perform in the second performance days later (in a reduced line-up of piano, clarinet, trumpet, trombone and tuba), and furthermore were among those he drew upon a couple of years later for the premiere of his Theatre Piece (1960) – a score whose instructions are obfuscatory to say the least –, suggests that some aspects at least of their playing were of interest to him. Tudor’s recollection of Butterfield’s playing in the Concert tears holes in the narrative pertaining to Cageian performance practice that has been constructed from that one notorious Stravinsky moment: ‘I remember the tuba player, a big guy, what was his name…Don Butterfield, a marvellous player. He did the piece so well!’[30]

Timing the Concert

As noted above, durations for each of the solos are not specified. The instructions state that ‘[t]he time-length of each system is free. Given a total performance time-length, the player may make a program that will fill it’. The onus is thus upon each player to assign durations to their music in some way – whether determined in advance or improvised is not specified – so as to arrive at a total duration, agreed perhaps collectively, or by one or more people. In early performances, that person was Cage, who dictated a duration of twenty minutes for the first performance and for a number of subsequent performances. It would seem that he ventured further than that, however, by writing in timings for each system in the players’ parts. Markings in what appears to be Cage’s handwriting can be seen in a copy of the Solo for Viola 2, prepared for what was, in effect, the third performance of the Concert, in New London, Connecticut, on 14 August 1958, when it was set to choreography by Merce Cunningham and formed the dance Antic Meet (1958). These show that each system is to last fifteen seconds, each page one minute and fifteen seconds, and all pages are to be used to reach a total duration of twenty minutes.

With much greater specificity, Cage wrote in 1959 to Friedrich Cerha that ‘in general the average length (which may be shortened or lengthened by a player but in a way which he predetermined and strictly adheres to) of a system for the string players is 15 seconds, for winds 20 seconds’.[31] The difference between strings and other players is accounted for by the fact that the string solos have 16 pages while all other solos contain just 12. Given that in, for example, the Solo for Viola 2 part, there are two pages with as many as 35 sounds distributed across them, this would average at just over two seconds per sound. This is by no means an impossibility, but there are instances whereby the player would have to think fast while negotiating the numerous indications for each sound, arriving at a decision as to whether the sound is to be soft or loud, short or long, in relation to the size of the note-head.

There are parts of some pages – already dense on average – where the activity is particularly hectic, such as the first line of the seventh page of the Solo for Viola 2. This contains ten sounds as follows: a high sul tasto harmonic followed by glissando and crescendo; a noise of some kind; a mid-range sul ponticello glissando with changing dynamics; another glissando with changing dynamics (this time a low note played normally); a high sul ponticello note bowed col legno with a rapid vibrato and changing dynamics; a low note with changing dynamics; a high harmonic played sul ponticello and col legno with glissando and changing dynamics; a slightly lower harmonic played normally with changing dynamics; a low pizzicato with the string stopped at the fingerboard; and a note a semitone higher played col legno with a medium speed vibrato, a glissando and a crescendo. Additionally, the player is required to add a mute between the second and third sounds, removing it after the sixth, and to add another (or the same mute again) for the plucked ninth sound, removing it immediately before the tenth sound.

All this, by Cage’s account, is to be accomplished within fifteen seconds. But according to the letter of the score, such a speed is not necessary, even to reach an agreed duration of twenty minutes. A player might choose to adopt a constant speed for each system to reflect the changing densities of the part – and it could be argued that slowing down during the busier systems, and conversely speeding up during the sparser ones, results in a more predictable averaging out of the rate of activity. Instead, by insisting that the players adopt the durations he stipulated, Cage removed one of the freedoms nominally given in the score.

Famously, Cage added a further complication to the issue of duration and speed of playing. A performance of the Concert may operate perfectly well under the conditions suggested above, with players measuring the durations of systems according to a stopwatch and finishing at an agreed time, but performances may also make use of a conductor. The role of conductor in the Concert is to change the rate at which the players measure time, acting as a sort of human clock.[32] The conductor – Cunningham at the Concert’s New York premiere – imitates the second hand of a clock, moving his left arm anticlockwise from the vertical up position to the vertical down position and passing the movement to the right arm which moves from the vertical down position to the vertical up position, indicating that one minute of time has passed. This motion continues until the agreed number of minutes – or rotations – has been completed. Unlike a stopwatch, however, the conductor changes the rate of movement according to a chart of timings which convert ‘clock time’ into ‘effective time’. For example, the first row of the conductor’s chart indicates that the time taken for the first fifteen seconds (that is, to move the left arm from the vertical up position to the horizontal left position) should be not fifteen seconds but 90 seconds, exactly six times slower than actual clock time.

The list of conversions fluctuates within a range of between eight times slower and two times faster than normal clock time, meaning that, by and large, performances will take longer than the agreed-upon duration specified at the outset. The first performance, for instance, lasted 23 minutes and fifteen seconds. Thus, in that performance, the ten events of the first line of the page described above may, in fact, have been distributed over up to two minutes, rather than the fifteen seconds indicated by Cage. However, although Cage organised the conductor’s chart to favour slower durations, it would also be possible for that same line to have been compressed into as little as seven-and-a-half seconds, an average of 0.75 seconds per sound. This, taking into account the mute changes, is almost certainly impossible. It is likely that Cage himself conducted the Connecticut premiere of Antic Meet, given that Cunningham was dancing, and we know him to have been the conductor of the subsequent Cologne performance of the Concert. Assuming that he followed the conductor’s part faithfully, the chances of any line moving faster than the duration marked in the part are a little under 1:3, meaning that this, and any of the other busy lines, may very well have been impossible to play as written with the timings Cage had inserted into the score.[33] One reading would be that Cage increased the chances of a ‘wild performance’ by stipulating durations that would add to confusion and chaos, requiring performers to omit notes, or possibly even systems, in order to keep up with the unrelenting and unpredictable human clock.

The conditions would appear to have been more disruptive still in Cologne. In his letter to Cerha, despite suggesting that shorter performances might utilise fewer pages, Cage states that in Cologne – and therefore, it may be assumed, in New York, too – all the pages were used. Yet archival evidence demonstrates that the players’ performance time (that is to say, the number of rotations) equalled ten minutes, resulting in an actual performance time of thirteen minutes. Unless Cage, writing just over a year after the Cologne performance, misremembered the process and in fact fewer pages were used, then the string players would have been asked to allocate seven-and-a-half seconds to each system, and the other players ten seconds. With the potential for moving up to twice as fast with a conductor, it is possible that a string player might have been required to move through a system in 3.75 seconds. If this was indeed the case, then Cage’s demands, both unnecessary and impracticable, would undoubtedly have resulted in resistance, and even scorn, from the ‘straighter’ classical orchestra players who performed in Cologne, notwithstanding the fact that the recording suggests that, in practice, these musicians by and large simply got on with the job in hand. Confusion would doubtless have been further increased by Cage’s reluctance to rehearse as an ensemble, believing that individual time spent with each musician was sufficient for a collective performance of solos.

Quite apart from the unusual demands of the notation, the playing circumstances and the function of the conductor, Cage’s performance decisions surely reveal his inexperience in dealing with musicians. Prior to the Concert, his music was generally performed by friends and close associates: before his partnership with Tudor, Cage was a regular performer of his own music, or worked with friends (including his then-wife, Xenia) in percussion ensembles, or with individuals such as pianist Maro Ajemian. His three previous large ensemble pieces – The Seasons (1947), Sixteen Dances (1950–51) and the Concerto for Prepared Piano and Orchestra (1950–51) – are essentially conventionally orchestrated and notated pieces, requiring conventional conductors and instrumental performers. Contact with the players would have been minimal, as would questions relating to technique. Earle Brown’s comments cited above are surely only half the truth: not only did Cage behave as if he expected all the musicians to be, if not like him, like Tudor, he also expected them to be able to perform the impossible. He may even, at that time, not have had a concrete sense of where the line between possibility and impossibility lay or, for that matter, where he wanted to draw it.

Performing the Concert today

Any individual or ensemble approaching the task of performing the Concert for Piano and Orchestra today must contend with the paradox of the contradictions that exist between the voice of Cage the composer– that is, the notations and instructions of and for his music – and that of Cage the performer – his practice. If we put to one side, however, what he did and examine more closely what he said, then a further set of observations can be made, irreconcilable with the above account, which concerns itself less with what he said and more with what he did. The remainder of this essay draws upon performances by, and interviews with, members of Apartment House, particularly their performance at the University of Leeds in July 2017 and its subsequent recording,[34] to point to further possibilities as to the Concert’s potentialities and limits.[35]

A collection of solos

Each of the Concert’s fourteen solo parts may be played as a solo, or may be performed in any combination with any number of the other solos, resulting in a total of 16,383 possible solo and ensemble configurations. Additionally, a number of related works may be performed with any of the solos or groups of solos, among them Aria (1958), Fontana Mix (1958), Solo for Voice 1 (1958), Solo for Voice 2 (1960), and WBAI (1960). As mentioned above, the second performance featured only five players, while a third performance, held within the same concert as the second, added a vocal part, specifically Solo for Voice 1. Subsequent performances and recordings have evidenced many other combinations, although there surely remains a large number of instrumental combinations that have never been explored. Irrespective of the size of the ensemble, what is clear from the titular emphasis upon these being solos, as well as from Cage’s practice in subsequent pieces, is that each player plays their part as a solo, creating, in performances featuring more than one player, a collection of solos. This is a well-known feature of Cage’s music from the early 1950s on, and performances generally look and sound as if the players are proceeding independently, regardless of what else is sounding (or moving) around them. Typical of Cage’s instructions and his own practice is his recollection of an invitation to play with the Joseph Jarman Quartet in 1965:

I advised them not to listen to each other, and asked each one to play as a soloist, as if he were the only one in the world. And I warned them in particular: ‘If you hear someone starting to play loud, don’t feel that this obliges you to play louder yourself.’ I repeated to them that they should be independent, no matter what happened.[36]

It is relatively common today to find ensembles, such as Apartment House, more than willing to adhere to the Cageian aesthetic of individual responsibility resulting in a ‘separate togetherness’ in performance. Yet discussions with the musicians of Apartment House revealed an uneasy tension between applying the focus necessary to observe the individual part and attending to the sounds being made around them.[37] Although extensive discussions had been undertaken with each musician, including some group discussions, in the months prior to the performance, there was very little ensemble rehearsal before the concert performance. A brief tutti rehearsal took place to enable sound and acoustic checks, staging decisions, and to provide sufficient familiarity with the overall sound and with the actions of the conductor. Otherwise the experience of the players in the concert was as fresh as that of the audience listening. Given the sometimes extraordinary techniques and sounds arising from the notations, it is no surprise that the attention of players tended toward the sounds and actions of others as well as their own. Players admitted to being delighted, curious and surprised by what was going on around them; there was little sense of players thinking of themselves as playing in isolation. Furthermore, despite understanding the concepts of independent playing and being familiar with Cage’s music more generally, a number of players also admitted to letting the freedoms permitted them in the notation provide them with the space to make choices which depended upon the actions of other players. This was particularly true of the string players, who were more than aware of the possibility of their sounds being inaudible in the context of a loud trombone or trumpet sound (or both) being played at the same time. Though they had no control over when the brass players might make a sound, they did have some control over the dynamics and time placement of their own sounds, within the parameters of the notation. A number of the string sounds are fragile and quiet, most obviously the col legno and sul tasto techniques and the use of mutes and harmonics, often in combination, mentioned above. As well as being quiet, these techniques often result in rich textural sounds, highly unusual given the date of composition. In the face of a loud sound elsewhere in the ensemble, instead of attempting a louder sound still, some players decided to wait a little before playing. Beyond these kinds of decisions, the sheer delight in the coincidences, counterpoints and colours arising when two or more instruments play in close proximity to each other was something that a number of players appreciated about the performing context.

Although any performance might be given without a conductor, with players utilising stopwatches or similar methods, an added collective dimension is in play when a conductor is involved. When the speed changes either way (usually heralded by an indication from the conductor’s spare hand) a collective change of energy and pace results. If the change is to a faster pace then, as one unit, the ensemble mobilises itself to negotiate the change in duration for the music ahead – although for how long is unknown, since the musicians are not privy to the composer’s directions which the conductor is following. As cellist Anton Lukoszevieze warned the ensemble, this can result in a collective scramble to play followed by an easing off of that initial panicky activity. When the tempo slackens, especially if by a significant proportion, there is another collective easing of energy, palpably felt by both players and audience alike.

Duration and density

Other than the considerably shorter Cologne performance, early performances involving Cage and Tudor, sometimes accompanying Antic Meet, consisted of twenty ‘conductor minutes’ – as evidenced by the numerous conductor realisations held in New York Public Library – and consequently an actual duration of around 23–26 minutes. This is true, too, of the 1964 ‘Tudorfest’ ensemble performance, and of more recent recordings by the S.E.M. Ensemble, the Barton Workshop and the Ostravská Banda.[38] A recording by Ensemble Modern is only slightly longer, at 30 minutes.[39] Part of the reason for this consistency is surely because the instructions provided for the conductor are, in fact, more like a realisation of some general principles: the third column of timings, the ‘omit’ column, makes sense only for ‘a twenty minute program’, that is, twenty rotations of the conductor’s arm. If a conductor is used for durations of other than twenty minutes then either the ‘omit’ column would have to be ignored (and timings recalculated) or a different set of timings be devised. A few other recordings are slightly shorter – lasting from fifteen to twenty minutes – but there currently exists no recording for large ensemble longer than the recent Apartment House recording, which has a total duration of 53 minutes, the result of 39 conductor rotations.[40]

There is nothing to suggest a preference for any particular duration beyond Cage’s early practice and the part for conductor. If both these are put to one side, one might imagine durations which range from the shortest (a few seconds, perhaps) to extravagantly long. However, there are consequences of extending a performance beyond this common 20–30-minute range: although the Solo for Piano is a score of extraordinary range and complexity, such that one might imagine a performance of it lasting several hours, the extent of the material available to the other instrumentalists is limited. The sixteen pages of the string parts represent a hard limit: Cage writes that, although any amount may be played, ‘no part once played is to be repeated’. This direction is omitted from the wind and brass solos: as mentioned above, their instructions suggest that ‘additional silences’ may be included. The emphasis, then, in the instructions is upon reduction rather than addition, just as the conductor tends to slow rather than accelerate, with the parts representing the maximum material available. If, then, a performance is extended over a long duration, the result will tend toward sparseness, even if all pages are played by all players. The varied and varying densities of sounds upon individual pages, in combination with the shifting speeds of the conductor (where there is one), will probably ensure periods of greater activity, both within a solo and across the ensemble; however, longer total durations will result in protracted silences, more solo and duo playing, and greater focus upon the qualities of individual sounds over the more chaotic ensemble textures of early performances. The performance given by Apartment House, made up of musicians not associated with jazz, (although including some experienced improvisers), in this sense, contrasts markedly to the early performances. This has consequences for the sounding result, bringing sounds into greater focus, clarity and transparency, and revealing an attention to sonority and depth of sound typical of players experienced in performing recent experimental and improvised music, but not typical of recordings of this piece of experimental music.

One of the features of Apartment House’s approach, distinct from the early performances and most contemporary ones alike, was the decision to observe the emphasis in the instructions upon individual decision-making.[41] Once a total duration had been decided – on this occasion the result of the piano realisation, worked backwards to obtain a number of conductor cycles and speeds (information shared only between pianist and conductor) – each player had free rein to decide how to assign durations and pages to their performance. Some decided to play all pages, others a selection, whether determined by chance procedures or not. Some players assigned consistent durations to each system, dividing the number of rotations equally across their part (playing, in one case, 39 systems only – equivalent to seven pages plus four systems – assigning a conductor rotation to each system) others made more varied assignations. One player made the decision to play only one page for the total duration, dividing the five systems such that each system was equal to just under eight rotations. The page selected contained a single sound, interpreted as a short sound, resulting in a performance by that player which consisted of a single sound lasting approximately half a second, preceded and followed by protracted periods of waiting and listening. Not only was this considered to be a justifiable course of action, respecting the dignity and rights of each player to make their own realisations as they saw fit, but it also guaranteed their freedom to make decisions regarding the articulation, timing and projection of their sounds. This decision, too, recollects Rehak’s questions around the premiere:

I said to Cage, ‘The instructions say “Play any sections, or none.” Does that mean I can get paid for just showing up for three gigs and not even open up my horn case?’ And he said, ‘Why, yes, if that’s what you want to do.’ And I said, ‘John, you’re my man. I’ll play for you any time.’[42]

New Readings

It is clear that the early performances, and many subsequent ones, present a particular kind of reading of the Concert, tending toward chaos and wildness. Yet the instructions allow for a far wider range of approaches, some of which may be entirely different in result from those which Cage demonstrated. It is also surely the case that the behaviour of the early performers, which has in any case almost certainly been exaggerated and mythologised, was in no small part a product of the specific interpretative – that is to say performance – decisions made by the composer. The issues raised by this music, and the history of its performances, are in part the result of those decisions, which represent a single and quite small set of possibilities among many. Dohoney has pointed to how ruptures in Cage’s practice of indeterminacy stem from his ‘authorial’ presence, seeking control over aspects of performance which are not directly stipulated in the notations.[43] It is possible, in the case of the Concert, that Cage’s expansion of his authority beyond, and in some cases in opposition to, what his notations suggested proved to be one of the principal obstacles in early performances. This would mean that the potentiality of his notations extends significantly further than that which he either permitted or was willing to explore through his practice.

Moving forward, there is much to be learned about Cage’s music through a stretching of performance possibilities beyond that which has become standard, in ways that seek not to subvert or, for that matter, sabotage the music but which probe it and reveal fresh insights into both how it might sound and how its performance might be undertaken. To do so requires a separation of Cage’s performance practices – and surely the practices of Tudor too – from the far richer set of possibilities afforded by the instructions and notations themselves.

References

Avakian, George, ‘About the Concert’, The 25-year Retrospective Concert of the Music of John Cage, (Wergo, WER 6247-2, 1992)

Brown, Carolyn, Chance and Circumstance: Twenty Years with Cage and Cunningham (New York, NY: Knopf, 2007)

Cage, John, ‘Indeterminacy’, in Hans G. Helms, ‘John Cage’s Lecture “Indeterminacy”’, Die Reihe, no. 5 (1959), pp. 115–120

Cage, John, and Daniel Charles, For the Birds, tr. Richard Gardner, Tom Gora and John Cage, eds, (London: Marion Boyars, 1981 [1976])

Cage, John, and Richard Kostelanetz, Conversing with Cage (New York, NY: Limelight, 1988 [1970])

Clarkson, Austin, ‘The Intent of the Musical Moment: Cage and the Transpersonal’, in David Bernstein and Christopher Hatch, eds, Writings Through John Cage’s Music, Poetry, + Art (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2001), pp. 62–112

Dachs, David, ‘Cage on Stage Is the Rage’, Cincinnati Times-Star, 31 May 1958, 12TV [source: George and Anahid Avakian Papers, New York Public Library]

Darter, Tom, ‘Interview with John Cage’, Keyboard Magazine, (September 1982), pp. 18–29

Dempster, Stuart, The Modern Trombone: A Definition of its Idioms (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1979)

Dohoney, Ryan, ‘John Cage, Julius Eastman, and the Homosexual Ego’, in Benjamin Piekut, ed., Tomorrow is the Question: New Directions in Experimental Music Studies (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2014), pp. 39–62

Feisst, Sabine, ‘John Cage and Improvisation: An Unresolved Relationship’, in Musical Improvisation: Art, Education, and Society, Gabriel Solis and Bruno Nettl, eds, (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2009), pp. 38–51

Iddon, Martin, and Philip Thomas, John Cage’s Concert for Piano and Orchestra (Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming)

Kim, Rebecca Y., ‘John Cage in Separate Togetherness with Jazz’, Contemporary Music Review, vol. 31, no. 1, (2012), pp. 63–89

Kirby, Michael, ‘The New Theatre’, in Mariellen Sandford, ed., Happenings and Other Acts (London: Routledge, 1995), pp. 29–47

Kotík, Petr, ‘A Visit with David Tudor: Notes from an Evening with David Tudor, Sarah Pillow, Joseph Kubera, Wolfgang Trager, Tina Trager, Didi Shai and Petr Kotík, (Tompkins Cove, NY, 14 September 1993)

Kuhn, Laura, ed., The Selected Letters of John Cage (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2016)

Lewis, George, ‘Improvised Music After 1950: Afrological and Eurological Perspectives’, Black Music Research Journal, vol. 16, no. 1, (Spring 1996), pp. 91-122

—-, A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music (Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press, 2008)

Miller, Leta E., ‘Cage, Cunningham and Collaborators: The Odyssey of Variations V’, Musical Quarterly, vol. 85, no. 3, (2001), pp. 547–67

Misch, Imke and Markus Bandur, eds, Karlheinz Stockhausen bei den Internationalen Ferienkurse in Darmstadt, 1951–1996 (Kürten: Stockhausen, 2001)

Parmenter, Ross, ‘Music: Experimenter (Zounds! Sounds by) John Cage at Town Hall, The New York Times (16 May 1958)

Piekut, Benjamin, Experimentalism Otherwise: The New York Avant-Garde and its Limits (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2011)

—-, ‘Indeterminacy, Free Improvisation, and the Mixed Avant-Garde’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, vol. 67, no. 3, (Fall 2014), pp. 769–824

Rehak, Frank, ‘A Call from Cage’, YLEM, Vol. 18, No. 10, (1998), p. 4

Tomkins, Calvin, The Bride and the Bachelors, (London: Penguin, 1978)

Yaffé, John, ‘An Interview with Composer Earle Brown’, Contemporary Music Review, vol. 26, nos. 3–4, (June/August 2007), pp. 289–310

Endnotes

[1] This essay draws upon research undertaken as part of the AHRC-funded project ‘John Cage and the Concert for Piano and Orchestra’. The three authors were joined by Christopher Melen, who developed the Solo for Piano app (available at https://cageconcert.org/), and the project featured interviews with, and performances by, Apartment House, with whom Philip Thomas plays piano. We are grateful to the musicians of Apartment House for their participation in this project.

[2] Leta E. Miller, ‘Cage, Cunningham and Collaborators: The Odyssey of Variations V’, Musical Quarterly, vol. 85, no. 3 (2001), p. 552.

[3] George Avakian, ‘About the Concert’, The 25-year Retrospective Concert of the Music of John Cage (Wergo, WER 6247-2, 1992).

[4] Calvin Tomkins, The Bride and the Bachelors (London: Penguin, 1978), p. 128.

[5] For detailed analysis of this and the European premiere recordings, see Martin Iddon & Philip Thomas, John Cage’s Concert for Piano and Orchestra (Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming).

[6] Ross Parmenter ‘Music: Experimenter (Zounds! Sounds by) John Cage at Town Hall, The New York Times (16 May 1958).

[7] George Avakian, op. cit.

[8] John Cage, ‘Indeterminacy’, in Hans G. Helms, ‘John Cage’s Lecture “Indeterminacy”’, Die Reihe, no. 5 (1959), p. 118.

[9] Carolyn Brown, Chance and Circumstance: Twenty Years with Cage and Cunningham (New York, NY: Knopf, 2007), pp. 226–27.

[10] Ibid.

[11] John Cage and Richard Kostelanetz, Conversing with Cage (New York, NY: Limelight, 1988 [1970]), pp. 68–69.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Austin Clarkson, ‘The Intent of the Musical Moment: Cage and the Transpersonal’, in David Bernstein, Christopher Hatch, eds, Writings Through John Cage’s Music, Poetry, + Art (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2001), pp. 72–73.

[14] John Yaffé, ‘An Interview with Composer Earle Brown’, Contemporary Music Review, vol. 26, nos. 3–4 (June/August 2007), pp. 300–301.

[15] Ryan Dohoney, ‘John Cage, Julius Eastman, and the Homosexual Ego’, in Benjamin Piekut, ed., Tomorrow is the Question: New Directions in Experimental Music Studies (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2014), pp. 39–62; Benjamin Piekut, Experimentalism Otherwise: The New York Avant-Garde and its Limits (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011).

[16] For further discussions of the musicians employed for the occasion see Iddon & Thomas, John Cage’s Concert for Piano and Orchestra.

[17] Frank Rehak, letter to Stuart Dempster, 17 December 1977, in Stuart Dempster, The Modern Trombone: A Definition of its Idioms (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1979), p. 96. For detailed discussion of the techniques required to play the Solo for Trombone, see https://cageconcert.org/performing-the-concert/orchestra/solo-for-sliding-trombone/

[18] Rehak at first ‘assumed that he was referring to the articulation of a jazz solo with a chordal reference and assured him that that was part of the business I was in’. Ibid.

[19] Sabine Feisst, ‘John Cage and Improvisation: An Unresolved Relationship’, Musical Improvisation: Art, Education, and Society, Gabriel Solis and Bruno Nettl, eds, (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2009), p. 40.

[20] John Cage to Peter Yates, 11 September 1961, in Laura Kuhn, ed., The Selected Letters of John Cage (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2016), p. 249.

[21] See https://cageconcert.org/performing-the-concert/orchestra/ for discussion of the notations used in the orchestral solos.

[22] Michael Kirby, ‘The New Theatre’, in Mariellen Sandford, ed., Happenings and Other Acts (London: Routledge, 1995), pp. 37–38.

[23] Tom Darter, ‘Interview with John Cage’, Keyboard Magazine (September 1982), p. 21.

[24] George Lewis, ‘Improvised Music after 1950: Afrological and Eurological Perspectives’, Black Music Research Journal, vol. 16, no. 1 (Spring 1996), pp. 99–100.

[25] George Lewis, A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music (Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press, 2008), p. 380.

[26] Benjamin Piekut, ‘Indeterminacy, Free Improvisation, and the Mixed Avant-Garde’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, vol. 67, no. 3 (Fall 2014), pp. 769–824.

[27] David Dachs, ‘Cage on Stage Is the Rage’, Cincinnati Times-Star, 31 May 1958, 12TV (source: George and Anahid Avakian Papers, New York Public Library).

[28] David Tudor to Karlheinz Stockhausen, 12 March 1957, in Imke Misch and Markus Bandur, eds, Karlheinz Stockhausen bei den Internationalen Ferienkurse in Darmstadt, 1951–1996 (Kürten: Stockhausen, 2001), p. 162.

[29] John Cage and Richard Kostelanetz, Conversing with Cage (New York, NY: Limelight, 1988 [1970]), p. 69.

[30] Petr Kotík, ‘A Visit with David Tudor: Notes from an Evening with David Tudor, Sarah Pillow, Joseph Kubera, Wofgang Trager, Tina Trager, Didi Shai and Petr Kotík. (Tompkins Cove, NY, 14 September 1993), p. 13.

[31] John Cage to Friederich Cerha, 15 October 1959 [source: Archiv der Zeitgenossen, Krems].

[32] See https://cageconcert.org/performing-the-concert/the-conductor/ for detailed discussion of the conductor’s role.

[33] It is by no means certain that Cage did use the conductor’s part: Petr Kotík recalls performing with Cage conducting in the 1960s, when he conducted without a score, improvising the timings (Interview with Petr Kotík, 14 May 2016).

[34] Apartment House, CC (Huddersfield Contemporary Records, HCR16CD, 2017).

[35] The Solo for Piano is not discussed in detail here. For a close examination of the notations, their meanings and applications in performance, see cageconcert.org as well as Iddon & Thomas, John Cage’s Concert for Piano and Orchestra.

[36] John Cage and Daniel Charles, For the Birds, tr. Richard Gardner, Tom Gora and John Cage, eds, (London: Marion Boyars, 1981 [1976]), p. 171. The occasion is discussed in detail in Rebecca Y. Kim, ‘John Cage in Separate Togetherness with Jazz’, Contemporary Music Review, vol. 31, no. 1 (2012), pp. 63–89.

[37] See film ‘Performing the Concert’ https://cageconcert.org/performing-the-concert/

[38] Music from the Tudorfest: San Francisco Tape Music Center 1964 (New World Records, 80762-2 [1964] 2014); The Orchestra of S.E.M. ensemble, Concert for Piano and Orchestra; Atlas Eclipticalis (Wergo, WER 6216-2, 1992); Barton Workshop, The Barton Workshop Plays John Cage (Etcetera, KTC 3002, 1992); Ostravská Banda, Ostravská Banda on Tour (Mutable Music, 2011).

[39] Ensemble Modern, John Cage – The Piano Concertos. (Mode, 57, 1997).

[40] A film of the complete performance may be viewed here https://cageconcert.org/performing-the-concert/apartment-house-and-philip-thomas-perform-the-concert-for-piano-and-orchestra/

[41] See film ‘Preparing parts for the Concert for Piano and Orchestra’ https://cageconcert.org/performing-the-concert/

[42] Frank Rehak, ‘A Call from Cage’, YLEM, Vol. 18, No. 10 (1998), p. 4.

[43] Ryan Dohoney, ‘John Cage, Julius Eastman, and the Homosexual Ego’, pp. 39–62.