Beethoven’s Dynamics in Keyboard Works

Table of Contents

Bart van Oort

Bart van Oort studied piano and fortepiano at the Royal Conservatory in The Hague. In 1986 he won the first prize and the Audience prize at the International Fortepiano Competition in Brugges, Belgium, and he subsequently studied with Malcolm Bilson at Cornell University (USA), receiving a Doctor of Musical Arts degree in Historical Performance Practice in 1993. He has since given lectures and masterclasses and performed all over the world. Since 1997 Van Oort has made over fifty recordings of chamber music and solo repertory, including the 4-CD box set The Art of the Nocturne in the Nineteenth Century, the Complete Haydn Piano Trios (10 CDs) with his ensemble the Van Swieten Society, with Malcolm Bilson and five other fortepianists the Complete Beethoven Piano Sonatas and, with four other fortepianists, the Complete Haydn Piano Sonatas. In 2006 Bart van Oort completed a ten-year, 14-CD recording project, the Complete Works for Piano solo and Piano four-hands of Mozart. With The Van Swieten Society he released various cds. Recently appeared French Nocturnes (Vol. 5 of The Nocturne in the Nineteenth Century), Dussek Piano Sonatas, Beethoven Piano Quartets. Bart van Oort teaches fortepiano and Historical Performance Practice at the Royal Conservatory in The Hague.

by Bart van Oort

Music & Practice, Volume 8

Explorative

To play Beethoven’s keyboard works on a modern piano instead of a contemporary fortepiano is a translation of sorts.[1] As in any translation, one loses part of the original meaning in the process. The modern player, like a translator, faces two problems: relative unfamiliarity with the language because two centuries of history have blurred the picture and a modern instrument that ‘pronounces the musical words’ differently. The first problem is unrelated to the instrument, as it is a question of understanding the musical language. We can solve the second problem when we have a ‘native speaker’ who pronounces the language for us: in this case, the eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century fortepiano. Instead of taking the notation of Beethoven and his contemporaries as the complete and unalterable truth, we must take into account that some aspects of their style could not be notated. Treatises of the time support this assumption: for instance, all treatises before 1800 agree that the application of dynamics belongs to the domain of the performer. As a result, early scores show little or no dynamics at all. The dynamics that are notated seem, almost without exception, very general.

Pianists of all times have of course instinctively understood this: not only dynamics, but also timing, rhythm (as opposed to metre), tone colour, tempo, tempo rubato, pedalling, balance between the hands, drive and direction, and subtle, speech-like accentuation, cannot be adequately recorded in our musical notation. But the degree to which these unwritten liberties have been exploited has diminished enormously in the 250 years since Beethoven was born: with the disappearance of the improvising performer, performance of the classical repertoire has become less free. Urtext editions have given a further blow to the artistic initiative of modern performers. Rather than a score that serves as a set of descriptions of the musical result, a drawing board for interpretation, Urtexts seem to imply that following the score literally means ‘fidelity’ to the text: in this view the notation is transmitted as a set of instructions. In this article I will describe one of these unwritten liberties – dynamics – in particular in the piano works of Beethoven.[2]

1. Understanding early dynamics

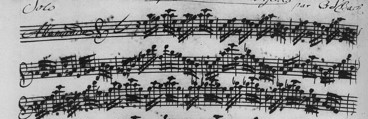

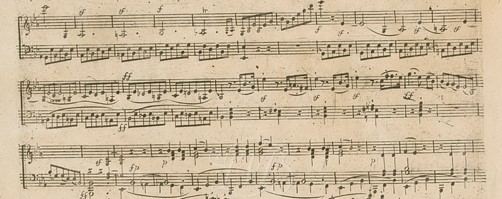

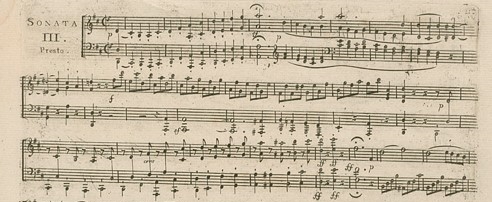

In much of the early keyboard repertory before ca. 1750 few or no dynamics are notated. In fact, one does not even find dynamics in scores for instruments that are highly dynamic, for instance, the Suites for harpsichord, cello or flute by Johann Sebastian Bach (Figure 1).

Bach’s two part Inventions and three part Sinfonias, written for the clavichord, were specifically meant to help students achieve a singing quality of playing: Yet Bach does not notate any dynamics.

There is a similar lack of notated dynamics in the early classical repertory. Dynamics were, nonetheless, considered to be of great importance: when Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach summarizes the elements of performance, he mentions dynamics first.[4] Haydn never indicated dynamics in his keyboard sonatas until the six Auenbrugger Sonatas, Hob. XVI/35–39 and 20, published in 1780. Even if it is true that these pieces were written with the harpsichord in mind, this does not explain the similar lack of dynamics in string quartets, symphonies and chamber music from the same period. This did not immediately change with the advent of classicism and the fortepiano, for which composers like C.P.E. Bach, Mozart and Clementi created a powerfully rhetorical, theatrical and, accordingly, dynamic style.

Mozart was one of the first composers to start notating dynamics in keyboard works. It is very likely that this had to do with the fact that his works were written with publication in mind. But even so, some of his (as well as of contemporaries’) later repertory for the fortepiano still had no dynamic markings. The Sonata in C Major, K. 330 (1781–3, published in 1784), has very few, and his late Sonata K. 545 (1788) – with its highly expressive second movement – has not a single dynamic marking. The genesis of this Sonata, described by Mozart himself in his thematic catalogue as ‘for beginners’, may have something to do with that: it was not published in Mozart’s lifetime and first appeared in print in 1805.

Character

The only dynamics one initially finds in early scores are forte and piano, and they seem to indicate character rather than dynamics. C.P.E. Bach explains that these two seemingly extreme markings are sufficient because they carry the possibility of a much broader range of dynamics.[5]

In his Klavierschule (1789), Daniel Gottlieb Türk confirms that ‘to indicate every single passage which should be played somewhat louder or softer than the previous or next one, is absolutely impossible’. Besides, there are many types of p or f; this even applies to the basic dynamic level of a piece.[6] Particularly interesting is the ‘Anmerkung’ (comment) following this paragraph in which he warns against an absolute interpretation of the indication of a general dynamic level. Such an absolute interpretation is precisely what happened half a century ago, when literal interpretation of the p and f markings led to the ‘terrace dynamics’ that enjoyed a brief twentieth-century popularity.

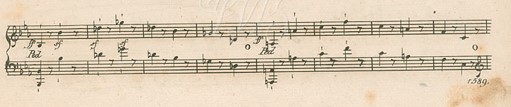

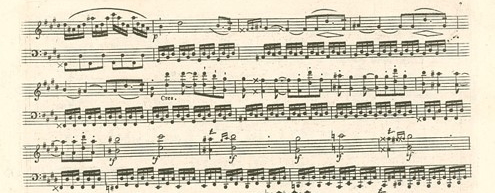

Many scores before 1800 lack an opening dynamic indication. The performer is expected to choose a dynamic that brings out the character. In the language of the early classical style (ca. 1750–90), for a slow movement, piano and, for a lively allegro the marking, forte is implied (Figure 2 shows the opening bars of a movement that implies forte). But how loud one really should play depends on the personal interpretation of the character. Typically, the second motive has a contrasting marking.

Figure 2 C.P.E. Bach, Sonata in E Minor, Kenner und Liebhaber V, Wq. 59/1 (1785), first movement, bars 1–4. (Breitkopf und Härtel, ca. 1895).

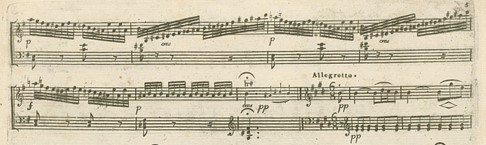

It follows that with an unusual opening character, the composer will need to indicate an opening dynamic. In C.P.E. Bach’s Für Kenner und Liebhaber he sometimes asks for a forte opening of a Larghetto or an Allegretto, as in the outcry of the opening passage on he dominant of the second movement of the Sonata in G Major, Wq. 56/2 (Figure 3).

Figure 3 C.P.E. Bach, Sonata in G Major, Kenner und Liebhaber II, Wq. 56/2 (1780), second movement, bars 1–5 (Breitkopf und Härtel, ca. 1895).

The performer’s domain

Not surprisingly, treatises of the second half of the eighteenth century treat dynamics as the performer’s domain. Leopold Mozart leaves no doubt about the responsibility of the performer: ‘The prescribed piano and forte must be observed most exactly … one must know how to change from piano to forte without directions and of one’s own accord’ (emphasis added).[7] Johann Joachim Quantz says that one of the duties of the accompanist is to understand the dynamics. He recommends the fortepiano over the harpsichord, since it is so much easier to follow the dynamics of the soloist. At the same time: ‘It may often happen that you must unexpectedly bring out or soften a note, even if nothing is indicated’ (emphasis added).[8]

Johann Adam Hiller explains in his Anweisung zum musikalisch-zierlichen Gesänge (1750) why there are no markings of intermediate dynamics. The difference does not need to be as large as piano and forte, because ‘there are so many intermediate degrees that we do not have enough names to indicate them all. All of these should be within the power of a good singer.’[9]

Türk, using the same argument, adds: ‘The performer must … himself learn to feel and judge which degree of loudness and softness reinforces the character that needs to be expressed. The added piano and forte only indicate the expression roughly and in a general way.’[10] Even at the end of the eighteenth century, Johann Peter Milchmeyer says that the many degrees of dynamics are hardly ever notated and can only be understood fully by a ‘very accomplished performer’.[11]

2. Implied dynamics

Understanding the musical language

While in the eighteenth century the application of refined dynamics was considered to be within the expressive domain of the performer, there are many ways in which composers indicated dynamics implicitly. Many of these implications are straightforward and in fact are described in most treatises, even though modern day performers may not always take the hint.

In order to ‘speak’ each musical ‘word’ (the musical motive) correctly, we need to design the correct emphasis (both accentuation and length). This accentuation depends on the harmonic tension within a musical motive, its gesture, articulation, and the melodic dissonance and consonance. Furthermore, the motive is placed strategically within the bar, which means that rhythm and metre play a role, as in Haydn’s London Sonata in C Major, Hob. XVI/52 (Figure 4) where the opening theme is displaced in the development. The subtle change in accentuation changes the nature of the theme and underlines the important arrival on F on the (now) first beat. Similar striking examples are found at the end of the expositions of Sonata Hob. XVI/32 in B Minor and Hob. XVI/46 in A flat Major.

Figure 4 Haydn, Sonata in C Major, Hob. XVI/50, first movement, bars 1–5 and 61–63 (Peters, 1937).

Creating a climax: shaping the phrase

Any musical phrase has but one climax. In order to understand where this climax takes place, the performer needs to consider the harmony, the harmonic rhythm, and the melody. While by around 1800 this climax is often identified by the composer with dynamic markings and/or accentuation, there is no such road map in the earlier classical works. The working of the harmony being of prime importance, the performer would understand that the grammar of the phrase necessitates a dynamic development, resulting in a crescendo–diminuendo towards, and from, the highpoint.

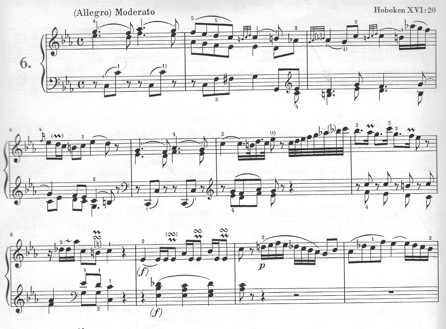

Figure 5 Haydn, Sonata in C Minor, Hob. XVI/20 (1771), first movement, bars 1–11, Urtext (Henle, 1972).

In Haydn’s Sonata in C Minor, Hob. XVI/20 (Figure 5) the climax on the downbeat of bar 7 is carefully crafted out by shorter figures, each building tension and giving direction. No dynamics are notated, as the working of slurs, bar hierarchy, harmony and diction provides sufficient information.

Early fortepiano style

Johann Joachim Quantz’s comments ‘Of the keyboardist in particular’ may have been addressed to his resident colleague C.P.E. Bach. Or perhaps he learned these dynamic strategies from Bach:

On a harpsichord with one keyboard, passages marked piano may be produced by a moderate touch and by diminishing the number of parts, those marked mezzo forte by doubling the bass in octaves, those marked forte in the same manner and also by taking some consonances belonging to the chord into the left hand, and those marked fortissimo by quick arpeggiations of the chords from below upwards, by the same doubling of octaves and the consonances in the left hand.[12]

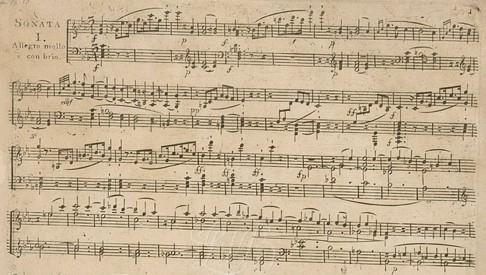

Similarly, in early piano repertory the number of notes has an impact on the volume: more notes means louder, fewer notes means softer. Deeper (as well as more) basses allow for greater volume, and melodies in octaves have a potential to be louder. Consequently, it is safe to assume that a classical composer asks for a louder context when the basses are deeper and the melody is written in octaves. On the first page of the first movement of his Sonata op. 10 no. 3 in D Major, Beethoven indicates but one crescendo and not a single diminuendo. But when texture and articulation are taken into account, a pattern of flexible dynamics arises from the page.

Figure 6 Beethoven, Sonata in D Major, op. 10 no. 3 (1796/98), first movement, bars 1–24, first edition (Eder, n.d.).

In bar 2, the double unisons become quadruple unisons, causing a crescendo which climaxes on the sf in bar 4 within the prevalent piano character. The second phrase climaxes on a dissonant D-sharp syncopation in bar 8 (the last note of line 1 in the first edition) which releases in the next bar. The tension build-up towards the D-sharp implies a crescendo, again within the piano character. This tension comes to the foreground in the forte of the third phrase, when the hands of the pianist diverge: the right hand rising and the left hand descending, a rhetorical gesture implying a crescendo. The climax of this phrase is in bar 15 (line 2, bar 7). The tonic D chord in bar 16 (second line, last bar) has less tension than the dominant on bar 15 and can therefore not be the loudest chord. Finally, the fourth phrase has a notated crescendo. Now the performer is asked to develop from the p to f character, aided again by an increasing number of unisons, and create three consecutive ff accents, the last one forming a climax on the quadruple unison[13] F-sharp in bar 22 (third line, bar 6).

Dissonance and consonance

Before 1800 the natural difference in dynamic level between a dissonance and a consonance was never indicated, as it was understood to reflect the normal accentuation of speech. Every treatise before 1800 mentions that a dissonance is to be played louder than the following consonance. Quantz: ‘The more, then, that a dissonance is distinguished and set off from the other notes in playing, the more it affects the ear.’[14] C.P.E. Bach agrees whole-heartedly.[15] His Sonata in G Major (Figure 7) from the fourth volume of Kenner und Liebhaber opens on the first downbeat with a melodic dissonance on top of the harmonic dissonance (V); the second downbeat has a melodic dissonance on a harmonic consonance (I). Both dissonances are gently louder than their resolutions but the downbeat of ‘bad’ bar 2 (de-emphasized by an ornament) is more relaxed and therefore less loud than the downbeat of bar 1, the ‘good’ bar. Naturally, the piano indication reinforces this dynamic pattern.

Figure 7 C.P.E. Bach, Sonata in G, Kenner und Liebhaber IV, Wq. 58/2 (1783), bars 1–4 (Breitkopf und Härtel, ca. 1895).

The correct performance of the slur

The rapid decay of the fortepiano tone is perhaps the most audible difference between the fortepiano and the modern piano. On a modern piano the tone has a soft attack, develops slowly, and sings for a long time before gradually dying away. The fortepiano tone has a sharp attack and fades quickly, which makes a natural articulation with the next tone easy and logical. The fortepiano touch is therefore fundamentally non-legato. If a performer on a five-octave fortepiano (all repertory from the period ca. 1750–1800) wants to play a sounding legato, the only way to do it is by playing diminuendo: the dynamic level of each new note then matches the rapidly decaying sound of the previous note.

But this diminuendo performance of the slur is not limited to the fortepiano alone: it is a key feature of the classical style. In his Versuch einer gründlichen Violinschule Leopold Mozart makes an enormous effort to impress on the reader the correct execution of the slur: he explains it in various words no less than 11 times within the treatise.

Now if in a musical composition two, three, four, and even more notes be bound together by the half circle, so that one recognizes therefrom that the composer wishes the notes to not to be separated but played singingly in one slur, the first of such united notes must be somewhat more strongly stressed, but the remainder slurred onto it quite smoothly and more and more quietly.[16]

This execution of the slur will make the performance articulated, clear and light; but the flow of the piece will change, the gesturing will be more outspoken and will gain in local expressive rubato (the beginning of each slur). The result is a colourful classicism rather than a lush romanticism.

The most frequently occurring slur is the two-note slur, the so-called Seufzer (sospiro, sigh). The Seufzer is a key signifier to the entire classical musical language and plays a prominent role in the music of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and all their contemporaries as well as continuing throughout the nineteenth century (see Figure 8 for an excerpt from one of Haydn’s sonatas). Leopold Mozart’s two elements defining any slur are crucial to the effect of the Seufzer. The first note (often dissonant) is louder and longer than the second, which is (in Mozart’s words) ‘slurred onto it quite smoothly and quietly, and somewhat late’. This leads to a refined rubato, which in a string of Seufzers may cause an lilting effect, reminiscent of the French inégale. The sweetness and delicateness of this figure explains why Seufzers appear so abundantly on the clavichord.

Figure 8 J. Haydn, Sonata in B flat Major, Hob. XVI/2 (1750s), first movement, bars 31–34, Urtext (Henle, 1971).

Register

Like the human voice, the early fortepiano has registers: the soprano is delicate, bright and transparent, the tenor (in which most of the melodies takes place) has a richer tone, the alto and bass registers are increasingly rich and gain in volume as well as length of the tone. The treble does not have a long-lasting tone, while its delicacy does not accommodate loud playing. Loudness in the high treble is only possible if the texture allows for it, for example a loud and full bass, an active middle voice, a harmonic pattern which allows for ample use of the pedal, and/or a melody in octaves.

As indeed in all of his keyboard works, most high notes on the first page of Mozart’s Sonata in B flat Major, K. 333 do not fall on a heavy beat (Figure 9). Of course, Mozart knows how to create a climax on a high note. This climax will need to take place on a heavy beat and must be sufficiently supported by middle voice and bass. In bar 9 there is a climax on F′‴, the highest note of Mozart’s piano.

Figure 9 W.A. Mozart, Sonata in B flat Major, K. 333 (1783). First movement, bars 7–10, Urtext der Neue Mozart Ausgabe (Bärenreiter, 1986).

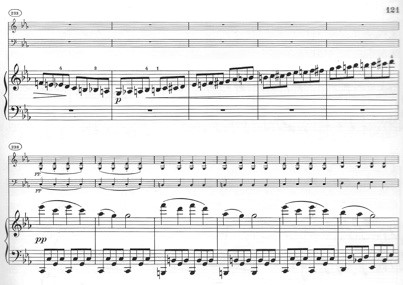

Beethoven, using the same five-octave piano as Mozart until about 1800 and therefore bound to the same dynamic restrictions in the treble as Mozart, nevertheless wrote very spectacular and loud passages in the treble. In order to not overplay the instrument, he needed to revert to the same techniques as Mozart. The Alberti Bass starting in bar 21 of the third movement of the Moonlight Sonata provides a powerful agitato energy (Figure 10). The balance between bass and treble on the five-octave Viennese fortepiano allows the left hand to challenge the right hand in volume. Instead of a lyrical melody with a rather suppressed left hand, the energy and tension arising from a loud and driving left hand is the key element of the agitato. With the start of the crescendo, the right hand melody is written in octaves. On the sforzandos the bass descends lower and lower, allowing for more forte.

Figure 10 Beethoven, Sonata in C sharp Minor, op. 27 no. 2 (1801), bars 20–32, first edition (Cappi, n.d.[1802]).

Touch

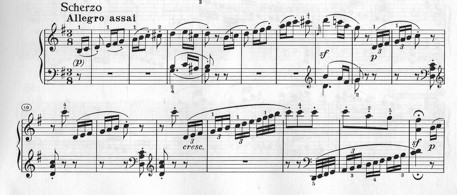

In Beethoven’s Sonata in E flat Major, op. 81a (Les Adieux), the 1953 Henle Urtext edition gives continuous dots for the left hand (Figure 11), where originally there were just wedges on the first five left hand figures (Figure 12). It seems that Beethoven intended the diminuendo after the highpoint[17] in bar 19 to be achieved not only by bringing down the volume, but also by softening the touch.

Figure 11 Beethoven, Sonata in E flat Major (Les Adieux), op. 81a, (1809–10), second movement, bars 19–20, Urtext (Henle, 1953).

Figure 12 Beethoven, Sonata in E flat Major (Les Adieux), op. 81a (1809–10), second movement, bars 18–21, first edition (Breitkopf & Härtel, n.d.[1811]).

Figure 13 Beethoven, Sonata in E flat Major (Les Adieux), op. 81a (1809–10), third movement, bars 37–44, first edition (Breitkopf & Härtel, n.d.[1811]).

In the first edition, the first four crotchets are marked ff, sf and have a wedge. The next four (in the same pedal) are still ff but without the wedge and sf. The next four (bars 40–41) are ff with wedges, no sf. In the new pedal these notes will therefore be less loud. The last four have no wedges and no sf. The net result is an 8 bar diminuendo to the p of the next passage (although the character change still makes a dynamic break logical). This notation is ‘completed’ in the 1953 Henle Urtext.

3. Interpreting dynamics

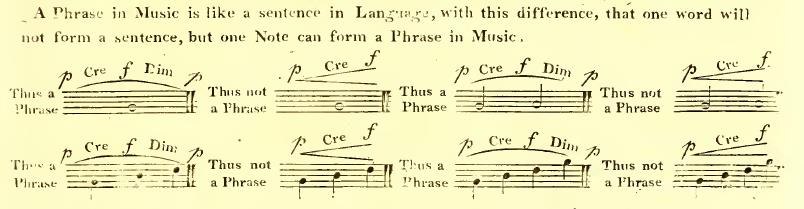

Tempo Rubato

While in early repertory dynamics can be completed through interpretation, dynamics that are notated may have a meaning beyond what is expected. Türk identifies a specific type of tempo rubato in his Klavierschule (1789), indicated with dynamics (Figure 14).[18] He mentions that one of the possible occurrences of tempo rubato is when the metrical accent on a ‘good’ note is transferred to an off-beat, or a ‘bad’ note: ‘these passages would work poorly when the notes are played exactly according to their notated length. The important notes must be played slowly and louder, the less important fast and weaker.’[19] And precisely this notation appears in Mozart’s Sonata in C Minor, K. 475, second movement, which is anyway full of rubato (Figure 15).

Figure 15 W.A. Mozart, Sonata in C Minor, K. 457 (1784). Second movement, bars 21–22, Urtext der Neue Mozart Ausgabe (Bärenreiter, 1986).

Counter accentuation

In his discussion of the correct performance of the slur, C.P.E. Bach mentions that the slur can create an accent against the metrical beat.[20] Leopold Mozart shows a four bar passage for which he proposes no less than 34 different bowings.[21]

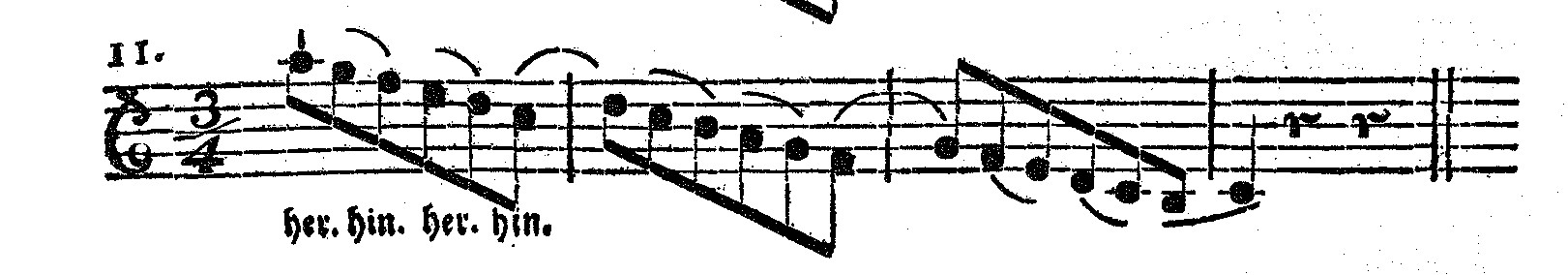

Mozart explains how the extraordinary bowings in no. 11 (Figure 16) change ‘the entire performance’ because the heavier first note of each slur falls on a weak beat.[22]

If the eccentric and striking slurs in the opening of the Scherzo of Beethoven’s Sonata in G Major, op. 14 no. 2 (Figure 17) are performed accordingly, the metre of the first two bars is not 3/8 but 2/8; the first note – the beginning of a slur, and therefore heavy – creates a beat and tapers off at the end of he slur, thereby removing the actual downbeat, and so on. The final C-sharp‴ of bar 2 is not connected to the notes before and after. This note, not belonging to the key of G Major, interrupts the 2/8 pulse. The listener suddenly understands that he has been fooled by the 2/8 metre and that it really should be a 3/8. The fact that bar 4 has no real downbeat (the last note under the slur is light and soft) makes it possible to play this trick again in bars 5–8. It is a a rhythmical joke, a scherzo in the real sense of the word.

Forte and fortissimo highpoint markings

A string of forte or sforzando markings indicating a succession of climactic notes aim at building to a climax, indicated fortissimo. In Beethoven’s Sonata in C Minor, op. 10 no. 1 (Figure 18), bars 72 and 73 are marked sf while bar 74 is marked f, obviously indicating the climax of this three-bar development. Similarly, three counterbeat sforzandos in bars 78–81 result in a climactic ff on the downbeat of bar 84; and same happens in bars 87–90.

Figure 18 Beethoven, Sonata in C Minor, op. 10 no. 1 (1796/98), first movement, bars 71–103, first edition (Eder, n.d.).

Since fortissimo indicates a climax, staying loud after this marking would produce just loud playing and make the moment of climax less effective. The sf on V7 in bar 60 in the first movement of the Pathétique Sonata (Figure 19), while still in the forte character, is therefore not even louder than the fortissimo fʹʹʹʹ with the argument that ‘no diminuendo is notated’.

Messa di voce

In his treatise Die Wahre Art das Pianoforte zu spielen (1799), Johann Peter Milchmeyer – like all his contemporaries – describes the correct performance of the slur in the same way as Leopold Mozart did so emphatically in 1755. There is an interesting addition to his description, however: in slurs longer than four notes the performer may add a crescendo–decrescendo, called messa di voce.[23] To Hiller this is one of the beauties in singing: ‘In legato passages of six or eight notes … one makes the middle notes somewhat stronger and the first and last weaker. This expressivity is indicated thus, < >.’ Hiller adds that the dynamics within a messa di voce can range from pianissimo to fortissimo.[24]

In fast pieces with short metres, Beethoven’s slurs easily stretch to four bars. In his Sonata op. 2 no. 2, the messa di voce in bar 27 is indicated fp (Figure 20). Two bars later the left hand imitation is written down differently. As the left-hand high point is even more important, the climax is indicated by sfp. But here the slur is broken: the heavier new beginning of the slur produces extra emphasis to help create the highpoint.

Figure 20 Beethoven, Sonata in A Major, op. 2 no. 2 (1795), first movement, bars 18–33, Urtext (Henle, 1952).

In the ‘Third Prerequisite for good singing’ of his treatise The Singer’s Preceptor (1810) Domenico Corri shows how the messa di voce – which he calls ‘the soul of music’ – can never end with a crescendo (Figure 21).[25]

Carl Czerny also devotes a paragraph on messa di voce. He shows two different ways to indicate it: crescendo–diminuendo, or hairpins, accompanied by the comment ‘It goes without saying that the performer must apply this expressivity himself, when the composer has not indicated it’.[26]

The slur in bars 1–2 in the opening of Beethoven’s Sonata in C Minor, op. 10 no. 1 has a slight stress in the middle, on the downbeat of bar 2 (Figure 22). The highest note, E-flatʹʹʹ, is almost the highest note of Beethoven’s piano. If it is reached with a crescendo it would be overplayed: the slur must end with a slight diminuendo (within the forte character) in order to end lightly, indeed as indicated by Beethoven himself by the dots on both E-flats. The net result is a messa di voce with a focus point on the downbeat of bar 2.

Figure 22 Beethoven, Sonata in C Minor, op. 10 no. 1 (1796/98), first movement, bars 1–50, first edition (Eder, n.d.).

In the second theme, the four-bar left hand slur starting in bar 33 focuses on the third bar, where the dominant appears. This messa di voce is carefully notated by Beethoven: to ensure the correct focus, the E-flat in the middle voice is tied before. The right hand downbeat of bar 3 is syncopated and therefore the third beat of bar 34, receiving most of the dynamic stress in the right hand, must be followed by a diminuendo. It follows that the f immediately following on the weak beat 2 of bar 35 is not to be played as the highpoint of this gesture.

The next four-bar gesture has the same structure, but the third gesture of this phrase starting in bar 41 (line 4, bar 5) is twice as long. A hairpin now indicates the highpoint of the entire phrase, creating an even larger messa di voce. Again, the highest notes of the melody (the A-flat in bar 41–42 and the B-flat in 42) are not to be played as dynamic highpoints.

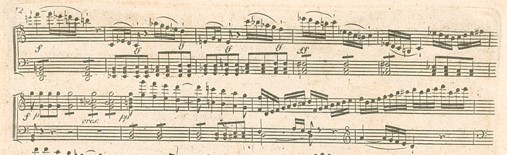

4. Subito dynamics

There are very few indications for bringing the volume down in classical works before 1800. Why is that so? One of the most striking features of the early piano is the rapid decay of its tone, which is one of the defining features of the instrument and its style. The classical phrase, moreover, has a lot of reason for decay. Like in speech, where practically every word has a soft ending, musical motives do not usually end with a loud note. In fact, most musical motives have a dynamic highpoint near or in the middle. Finally, the musical phrase itself has a natural decay: the climax of the classical phrase falls at about three-quarters of the length of the phrase (exceptions abound, obviously: composers know this feature of musical diction all too well). This means that there are one or two bars left for the tension to reduce at the end of the phrase, with a decrease in volume naturally resulting. In slow movements the high point may fall a bit earlier, leaving more space for winding down.

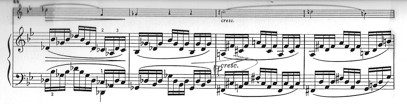

Beethoven’s piano works are replete with passages in which an f or ff is followed – within the space of one, two or more bars without additional dynamic marking – by a p or pp, usually interpreted as ‘subito pianos’. But the alternative, a diminuendo, is musically very attractive: f or ff often indicate a climax, after which a decay would be logical.

In Beethoven’s Piano Trio in C Minor, op. 1 no. 3, the notated dynamics range from ff to pp, and the work is full of sf, fp and rinsf markings, highlighting the dramatic content. Yet, there is not a single crescendo or diminuendo marking in the entire piano part. Instead, Beethoven used an occasional hairpin to indicate large messa di voces (three times); two crescendo and only one (!) diminuendo hairpin (iv/230–233). In all, there are far fewer hairpins in this trio than in the much milder first trio in E flat major and the lighthearted second trio in G major. It is of course unrealistic to believe that in this magnificent, theatrical work exploding of expressivity, Beethoven did not ask for more dynamic development than in these few cases.

Figure 23 Beethoven, Piano Trio in C Minor op. 1 no. 3 (1793–94), first movement, bars 348–53, Urtext (Henle, 1969).

In the coda of the first movement of in C minor piano trio (Figure 23) the ff outburst in all three instruments (bar 350) is followed by a return of the previous pp. No diminuendo is indicated – at first glance. But the harmony is a dominant–tonic release (on a pedal point), and both cello and piano right hand have a slur, meaning a decay. The right hand scale descends, implying diminuendo; and the left hand chord has its natural decay, which makes it less logical for the right hand to try to maintain its ff. The cello is marked cresc. leading to the notated f outburst, probably to counter the natural tendency to create a messa di voce in each bar of this figuration (by the way, the cello part in this first movement has the only cello crescendo markings in the entire set of three trios). After creating the climactic downbeat of bar 350, the cello will want to diminish in order to make sense out of the f marking – or else why did Beethoven not notate f at the end of the bar, if the crescendo should continue? So, although technically speaking the fortissimo could be maintained in the right hand and a subito p could be achieved, Beethoven did not have to further specify his intentions to the contrary.

Crescendo as rinforzando

Today crescendo is mostly interpreted as ‘getting louder until the next marking’. This has, all by itself, created a style of playing that is full of dynamic surprises, even where the character of the piece does not seem to ask for it. A different picture arises from eighteenth-century treatises – one in which a crescendo describes an increase of volume just for the notes under which it is written. This means that the crescendo functions as a local rinforzando.

This is indeed what Leopold Mozart writes: ‘Crescendo: means increasing, and tells us that the successive notes, where this word is written, are to increase in tone throughout’[27] (emphasis added). Türk mentions the fact that a performer sometimes may not know exactly how long the crescendo is to last: ‘Since at the word crescendo one can not exactly know how long the gradual increase must last, some would write a f (forte) under the note which is to be played with full loudness.’[28] With this he implies that the crescendo may not continue if the target dynamic is not actually there.

A striking example of this rinforzando use of the crescendo is found in the second movement of Mozart’s Sonata in C Minor, K.457 (Figure 24). Besides a showcase of thematic variation, ornamentation and rubato notation, this magnificently detailed and meticulously notated movement is full of dynamics. Some of these crescendo markings are followed by a p.

Figure 24 Mozart, Sonata in C Minor, K. 457 (1784), second movement, bars 13–16, Urtext der Neue Mozart Ausgabe (Bärenreiter, 1986).

The first three demisemiquaver slurs starting on the third beat of the first bar are not marked crescendo. The slur, starting p with an expressive middle, asks for a mild messa di voce. Two more figures with a crescendo marking can now be interpreted as reinforcing the messa di voce expressivity of the middle of the slur. It is an open question whether the diminuendo on the last notes of the slur actually go down to the p level.

In the second movement of Beethoven’s Frühlings sonata for violin and piano, op. 24 (Figure 25), a crescendo in bar 6 reinforces the ascending interval E-flat–G in the melody, creating a melodic messa di voce. The descending flourish after the third beat releases the tension and diminishes to p.

Figure 25 Beethoven, Sonata in F, op. 24 Frühling (1800–01), second movement, bars 5–8, Urtext (Henle, 1978).

Several older, famous interpretations of this passage agree with this interpretation. More recent performances aim for a more spectacular subito interpretation.[29] It seems that this style of interpreting Beethoven’s crescendos in an absolute way is rather recent, belonging to a perspective in which a composers’ notation is interpreted as an instruction, rather than a description. It has resulted in new aesthetics which put more value on contrasts, as if the subito dynamic is what the passage ‘is about’.

Figure 26 Beethoven, Sonata in F, op. 24 Frühling (1800–01), second movement, bars 44–47, Urtext (Henle, 1978).

Arguments for the crescendo under the two bar violin slur in bars 46–47 (Figure 26) to be interpreted as a messa di voce are not only the slur itself, but moreover the fact that the last beat of bar 47 is a harmonic resolution. The diminuendo connected to this release does not necessarily bring the volume down completely to p; as in Figure 26, some break is still possible.[30] Other crescendos in this movement may be treated in the same way.

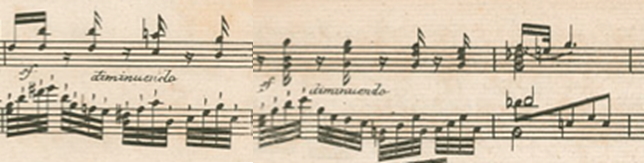

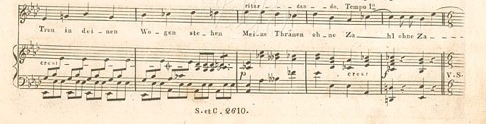

Actual subito piano

Subito piano does exist, of course. When there are dots following cresc. they indicate that the crescendo continues without a tapering off, ruling out the option of a messa di voce. While Mozart never uses dots after a crescendo marking, Beethoven does so frequently. In An die Ferne Geliebte (Figure 27) most of the crescendo markings are followed by dots. In the third song Beethoven leaves no doubt about the fact that he wants a subito piano on ‘meine Thränen’.

Figure 27 Beethoven, An die Ferne Geliebte, op. 98, III: ‘Leichte Segler in den Höhen’, first edition (S.A. Steiner & Co., n.d.).

But what to do when there are no dots? The necessity for a dynamic break must then be determined from the context. A subito piano interrupts the normal flow of the musical diction, this disruption is in fact its main purpose. Therefore, for a subito piano one or more out of three requirements need to be met: a harmonic break, a melodic break, or a rhythmic break.

There is no doubt about Beethoven’s intentions in the C minor trio, op. 1 no. 3, fourth movement (Figure 28). The logic is in the melodic break (subito back to thematic material) and a rhythmical break, the re-entry of the motoric Alberti bass.

Figure 28 Beethoven, Piano Trio in C Minor, op. 1 no. 3 (1793–94), fourth movement, bars 233–43, Urtext (Henle, 1969).

In the Waldstein Sonata op. 53 (Figure 29), the pp coda is introduced by a repeated dominant octave turning into a diminished chord: there is no way the volume can go down during the course of this dissonant harmony so the pp must be subito, now charged with dominant tension and the drive of the previous repeated octaves.

Figure 29 Beethoven, Sonata in C Major op. 53 (1803–04). First movement, bars 254–264, first edition (Bureau des Arts et d’Industrie, n.d., 1805).

A rhetorical interruptio is found in Beethoven’s Rondo in G Major, op. 51 no. 2 (Figure 30), where the gesture of bars 105–106 does not come to its conclusion but instead is interrupted by a literal repeat (bars 107–108). Because of the interruption of the musical thought bar 107 will be subito p. Upon the repeat, the gesture reaches a climax in bar 109.

Figure 30 Beethoven, Rondo in G, op. 51 no. 2 (1797), bars 105–113, first edition (Artaria, n.d.).

Conclusion

While initially the application of dynamics was the domain of the performer and therefore the notation of dynamics was sparse and general, towards 1800 composers started to write more refined dynamics. However, even when more and more different indications came into use, the way composers notated them was still based on earlier practice. In many passages dynamics are not notated but implied. In these cases the performer must base decisions about the realization of dynamics on an understanding of the musical language: rhetorical content, character, harmony, harmonic and melodic dissonances, correct performance of the slur, register, and notated touch. On the other hand, dynamics that are notated are in need of interpretation. They may indicate character, tutti or solo passages, or a contrast. In each of these cases the notated ‘dynamic’ marking is not primarily an indication of volume. Furthermore dynamics can have meaning beyond an effect on the volume: they may indicate rubato or a climax, or create an unusual metrical effect, a messa di voce, or rinforzando.

In modern performance Beethoven’s dynamics are often interpreted too literally. This has implications for the characterization, the flexibility of dynamics, and the rhythm, and it can result in an excess number of subito dynamic changes and an overly strict metrical execution. On (all of) Beethoven’s pianos, high notes need to be treated delicately, while on the modern piano they can and often will be played louder, in a (later) romantic spirit. The correct performance of classical slurs, meticulously described in classical as well as early romantic treatises, relies heavily on dynamics as well as rubato. This is an essential element of the rhetorical style. Modern performance treats slurs primarily as a technical indication (legato), and in doing so often replaces rhetorical classical ‘speaking’ by romantic singing.

Endnotes

[1] This article is based on Bart van Oort, ‘Understanding Classical and Early Romantic Dynamics 1750–1830’, Piano Bulletin 34/1 (2016), 38–52 (Part 1), and 34/2 (2016), 73–82 (Part 2). The research was supported by a research grant from the Royal Conservatory, The Hague.

[2] In this article I will not comment on accentuation markings, nor on dynamics which may imply the use of a pedal (like ppp, which may indicate the use of the moderator pedal in early romantic works). The difference between decrescendo and diminuendo in Schubert is described in van Oort, ‘Understanding Classical and Early Romantic Dynamics’.

[3] J.S.Bach Preface to his Inventions, BWV 772-801: Auffrichtige Anleitung wormit denen Liebhabern des Clavires, besonders aber denen Lehrbegierigen, eine deütliche Art gezeiget wird, nicht alleine (1) mit 2 Stimmen reine spielen zu lernen, sondern auch bey weiteren progressen (2) mit dreyen obligaten Partien richtig und wohl zu verfahren, anbey auch zugleich gute inventiones nicht alleine zu bekommen, sondern auch selbige wohl durchzuführen, am allermeisten aber eine cantable Art im Spielen zu erlangen, und darneben einen starcken Vorschmack von der Composition zu überkommen. / Forthright instruction, wherewith lovers of the clavier, especially those desirous of learning, are shown in a clear way not only 1) to learn to play two voices clearly, but also after further progress 2) to deal correctly and well with three obbligato parts, moreover at the same time to obtain not only good ideas, but also to carry them out well, but most of all to achieve a cantabile style of playing, and thereby to acquire a strong foretaste of composition.

[4] C.P.E. Bach, Versuch über die Wahre Art das Klavier zu spielen (1753 and 1762), Facsimile reproduction (Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1986). Part I, Chapter III: Performance (1753), 2nd edn (1787), 87.

[5] Bach, Versuch (1753), 1st edn, Part I, chap. III: ‘Vortrag’ §29, 129.

[6] Daniel Gottlieb Türk, Klavierschule (1789), facsimile reproduction (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1972), Part III, §30, 349.

[7] Leopold Mozart, Versuch einer gründlichen Violinschule (1756), 2nd edition (1787), chap. 12, §8.

[8] Johann Joachim Quantz, Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte Traversiere zu spielen (1752), translated as On Playing the Flute by Edward R. Reilly (New York: Schirmer, 1985), chap. 17 ‘Von dem Pflichten derer, welcher accompagniren’, 175.

[9] Johann Adam Hiller, Anweisung zum musikalisch-zierlichen Gesange (1780) Chap. II, §8, 22.

[10] Türk, Klavierschule, chap. 6 Part III, §29, 348.

[11] Johann Peter Milchmeyer, Die Wahre Art das Pianoforte zu spielen (1797) chap. IV: ‘Vom Musikalischen Ausdruck’, 48.

[12] Quantz, On Playing the Flute, chap. XVII Section VI, §17, 259.

[13] The prudent publisher of this sonata stayed within the five octave range of the standard instrument of his time. However, new instruments had already been equipped with the F sharp″ and Gʹʹʹ.

[14] Quantz, On Playing the Flute, chap. XVII, §12, 227.

[15] Bach, Versuch, Part I, Chapter III: ‘Vom Vortrage’, §29, 129.

[16] Leopold Mozart, Versuch einer gründlichen Violinschule (1756), translated as A Treatise on the Fundamental Principles of Violin Playing by Edita Knocker (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), chap. 7, section 1 §20. The slur is novel enough for his readers that it even needs explanation as a sign.

[17] Possibly the placement of this sf is more subtle than shown in Henle and is meant for the second semiquaver in the right hand.

[18] Türk, Klavierschule, chap. 6, Part V, §72, 375.

[19] Türk, Klavierschule, chap. 6, Part V, §72. 371. See also Haydn Sonata in C Minor Hob. XVI/20 (1771), first movement, bar 14.

[20] Bach, Versuch, Part I (1753), chap. III: Vom Vortrage, §18, 94.

[21] Mozart, Versuch, chap. 7, Part 1, §§ 19–20, 131–136.

[22] Mozart, Versuch, chap. 7, §20, 136. See also Türk Klavierschule, chap. 6, Part II, §13.

[23] Milchmeyer, Die Wahre Art das Pianoforte, 46.

[24] Hiller, Anweisung, Chap. II, §8.

[25] Domenico Corri, The Singer’s Preceptor (London, 1810), 65.

[26] Carl Czerny, Vollständige theoretisch-practische Pianoforte-Schule, op. 500, Part III: ‘Von dem Vortrage’ (Vienna: A. Diabelli, 1839, 2nd edn Vienna, 1846; facsimile reproduction of 2nd edn Wiesbaden: Breitkopf und Härtel, 1991), chap. 1: ‘Von der Anwendung des crescendo und diminuendo’, §4, 13.

[27] Mozart, Versuch, trans. Knocker, Part III, chap. I, 131–136; §27, 52.

[28] Türk, Klavierschule, chap. 1, §79, 117.

[29] Diminuendo on the third beat of bar 28: David Oistrakh/Lev Oborin, Henryk Szeryng/Arthur Rubinstein, Gidon Kremer/Martha Argerich. Crescendo to the barline of bar 28 and subito p on bar 29: Sebastian Müller/Nico de Villiers, Dora Bratchkova/Rudolf Meister, Anne Sophie Mutter/Lambert Orkis. All performances are available on YouTube.

[30] Diminuendo on the last beat of bar 47: David Oistrakh/Lev Oborin, Henryk Szeryng/Arthur Rubinstein. Subito p on bar 68: Gidon Kremer/Martha Argerich, Sebastian Müller/Nico de Villiers. Very much subito piano on bar 68: Sebastian Müller/Nico de Villiers, Anne Sophie Mutter/Lambert Orkis. All performances available on YouTube.